The (Less) United States?: Federalism & Decentralization in the Era of COVID-19

December 10, 2020

Alexandra Artiles, Martin Gandur and Amanda Driscoll

-

Introduction

On March 6, 2020, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear declared a state of emergency in response to the novel coronavirus, and would issue a stay-at-home order before the end of the month. Governor Bill Lee of neighboring Tennessee would enact the same emergency declarations and stay-at-home orders, albeit roughly a week after Governor Beshear. Both governors took early actions to `slow the spread,’ but the similarities in the governors’ responses end there. The number of days Kentucky businesses were closed was nearly twice (66 days) that of Tennessee (34 days). Come July, Governor Beshear would mandate the use of face-coverings, while Governor Lee would make no similar state-wide requirement, leaving the decision to do so to county and local officials.

Kentucky and Tennessee are nearly equal in terms of ethnic composition, income, and population . Yet, the two governors’ approaches led to dramatically different public health outcomes.[1] The July 31st statewide COVID-19 incident rate in Kentucky was less than half of that (45%) of Tennessee. Beyond health outcomes, Tennessee has experienced higher rates of unemployment, hospitalization, and mortality than Kentucky as a result of the coronavirus pandemic (CDC 2020a).

These discrepancies are emblematic of the tradeoff of U.S. federalism in the time of COVID-19: federal devolution permits state governments maximal flexibility to localize policy as needed, yet state responses and crisis mitigation are distributed unequally across the states (Petersen 1995). We review here the myriad of ways that federalism has shaped the governmental response to the dual health and economic crises brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. We describe the federal government’s decentralized response, and chart states’ efforts at crisis mitigation. We suggest that the limited federal response to the crisis, and the intentional devolution to the states, reverses a century long trend of policy centralization in the hands of the federal government (Artiles et al. 2020).[2]

-

Federalism in the U.S.: The 20th Century Expansion of Federal Power

Since the 1930s, the U.S. has witnessed slow but continual centralization across the vast most policy domains. President D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ administration marked the first phase of centralization, when the federal government expanded with the aim of providing economic relief to millions left in ruin by the Great Depression. The New Deal created social safety net programs that sought to combat homelessness, rural poverty, nationalized unemployment, and provide universal social security. This coordinated federal relief was simply beyond the capacity of any one state to unilaterally provide (Kincaid 2018).

The second phase of federal centralization began in the 1960s, under President Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ program, a sweeping political agenda that aimed to address long-institutionalized patterns of racism and racial segregation, eradicate poverty, reduce crime, abolish inequality, and improve the environment. Medicare and Medicaid were established at this time, providing healthcare to millions, while other federal programs targeted elderly and youth constituencies. These two periods of dramatic federal power expansion over the course of the 20th century imply the federal government’s reach now extends far beyond its narrow constitutional prerogatives.

-

The Much-Less United States?: Federalism in an Era of COVID-19

The federal response to the crises brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic stands as a dramatic about-face to the century-long trend towards federal government empowerment. The federal government’s initial reaction to the looming pandemic crisis was disjointed and at times contradictory, a response that stood in stark contrast to the strong and highly coordinated federal responses crises had elicited in decades past. The first known case of COVID-19 in the United States was diagnosed on January 21, 2020, when a U.S. citizen returned from travel to mainland China. By the end of January, it was confirmed that the virus could be transmitted from person-to-person, implying a likelihood for community spread. One prominent White House liaison predicted that COVID-19 “could infect as many as 100 million Americans, with a loss of life for as many as 1-2 million souls” (Schwellenbach 2020). Yet at the same time, President Trump confidently asserted the contrary, stating that “we have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. It’s going to be just fine,” (Schwellenbach 2020). On February 9, the White House Coronavirus Task Force met with governors to discuss the pandemic, which Maryland Governor Larry Hogan later described in jarring terms: “when I left that briefing…we knew this was going to be a serious crisis” (Schwellenbach 2020).

Most of the subsequent major federal actions would be taken by the end of March. On March 2, Vice President Pence declared that “mitigation, not containment,” was the new goal, a goal that would be abandoned by mid-October (Schwellenbach 2020). The federal government purchased 500 million N95 respirators, and President Trump signed an $8.3 billion emergency response bill on March 6, 2020. One week later, Congress passed The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, creating paid sick leave for COVID-19 related absences, establishing free COVID-19 testing centers, and expanding unemployment benefits. In March’s final days, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provided $100 million to hospitals to care for COVID-19 patients, and the Senate passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the largest economic aid package in U.S. history (Schwellenbach 2020).

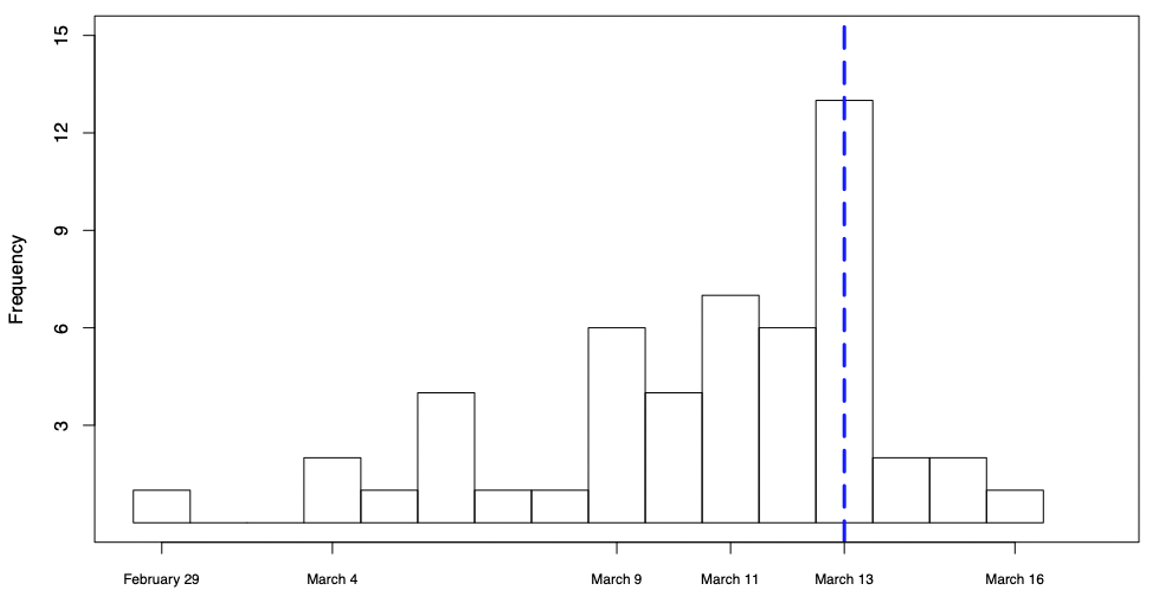

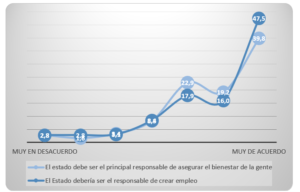

In spite of this historic mobilization of resources, the White House continued to downplay the pandemic, and stalled the declaration of a state of emergency. Figure 1 shows a time-line of states’ emergency declarations, with the dotted line indicating the date on which the federal government issued its emergency declaration, on March 13th, 2020. Washington State was the first to issue a state of emergency on February 29th, followed by California and Hawai’i on March 4th. By the following Monday, an additional 13 states declared state-wide emergencies, such that 5 days prior to the federal emergency declaration, a near-absolute majority (49.55%) of Americans resided in states where emergencies had been declared (Coleman 2020).

Figure 1. States’ Emergency Declarations Preceding Federal Declaration

Figure 1 makes clear that a plurality of states’ (13) emergency declarations coincided with that of the federal government. Although President Trump’s declaration retroactively declared the emergency (and subsequent order) to have been in effect from March 1, 2020, critics claim that, had the federal government made this declaration sooner, Americans would have taken the threat more seriously (Hsiang et. al 2020). By the end of March, nearly every state had an emergency declaration in place, with most issuing stay-at-home orders, while also closing businesses and schools. President Trump openly opposed these state-level shutdowns, saying that he would “love to have the country opened up and just raring to go by Easter” (Schwellenbach 2020).

Yet another foible was the federal government’s approach to testing: although the World Health Organization (WHO) sent hundreds of thousands of tests to the U.S., the Trump administration opted to rely exclusively on tests developed by its own Center for Disease Control (CDC). It was later revealed that many of the CDC tests contained a faulty reagent, preventing many labs from proceeding with testing (Cohen 2020). Consequentially, the U.S. continued to report artificially low case numbers throughout February (Schwellenbach 2020), and further enabled the belief that the pandemic was not a serious public health threat (Cohen 2020). President Trump would privately acknowledge COVID-19 as “more deadly than even your strenuous flus,” all while publicly downplaying the seriousness of the looming global pandemic (Glasser 2020).

State governments quickly became pivotal in managing the health and economic crises, with the President telling governors “you’re going to call your own shots” (Liptak et al. 2020). Although some governors quickly took to the reins of crisis management, others decried the federal government’s approach to be a dereliction of federal duty, and—worse yet, a political move by President Trump to avoid electoral responsibility for pandemic related hardship (Cook and Diamond 2020). Former Maryland governor O’Malley described: “[This] is a Darwinian approach to federalism; [it] is states’ rights taken to a deadly extreme” (Cook and Diamond 2020).

3.2. The States Take Charge

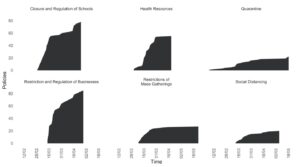

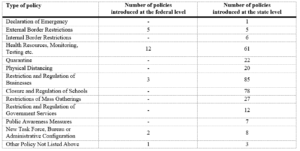

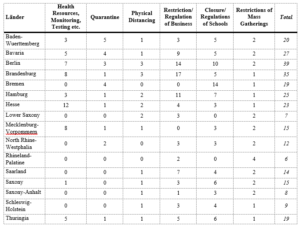

How did states respond to the public health crisis, and what did they do with their newfound authority? We summarize data compiled by the COVID-19 US State Policy Database (Raifman et al. 2020), that chronicles measures taken by states to respond to the twin health and economic crises spurred by the pandemic. We then compare COVID-19 incident rate (infections per 100,000 people) across states as of July 31st (Johns Hopkins CSSE COVID-19, 2020), and find great variation between states’ responses. We suggest some of this variance can be explained with reference to population density: with early COVID-19 outbreaks constrained to the costal urban centers, sparsely populated interior states did not face the same pressure to impose restrictive measures.[3] Yet a clear political pattern to states’ policies is also evident: while states that adopted restrictions were governed by leaders of both major parties, Republican affiliated governors tended to impose far fewer COVID-19 related restrictions.

As described above, all states, territories and several major cities declared formal states of emergency, allowing executives to mobilize resources to combat the coronavirus. A related policy, taken up by thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia (DC) were ‘stay-at-home’ or ‘shelter-in-place’ orders, which discouraged residents from leaving their homes for any reasons other than doctors’ visits, grocery store or pharmaceutical shopping. This would coincide with the mandated closure of restaurants, bars, and non-essential retail operations in 49 states and the District of Colombia.

The shuttering of the world’s largest economy brought with it an unprecedented economic collapse that eclipsed previous crises by orders of magnitudes (Kiefer 2020). With the help of the federal stimulus package, the states became the conduit for relief provisions and support for millions of newly unemployed Americans. Only five states declined to provide some sort of eviction relief—either by suspending judicial proceedings or formally loosening enforcement mechanisms. Thirty-four states prohibited shutting off utilities or gas to homes for COVID-19 related claims. Finally, there was an across-the-board expansion of social safety net investment by the states: every state (and DC) increased access to food security programs and healthcare for lower-income families (Medicare), and many also loosened restrictions for extended access to unemployment benefits.[4]

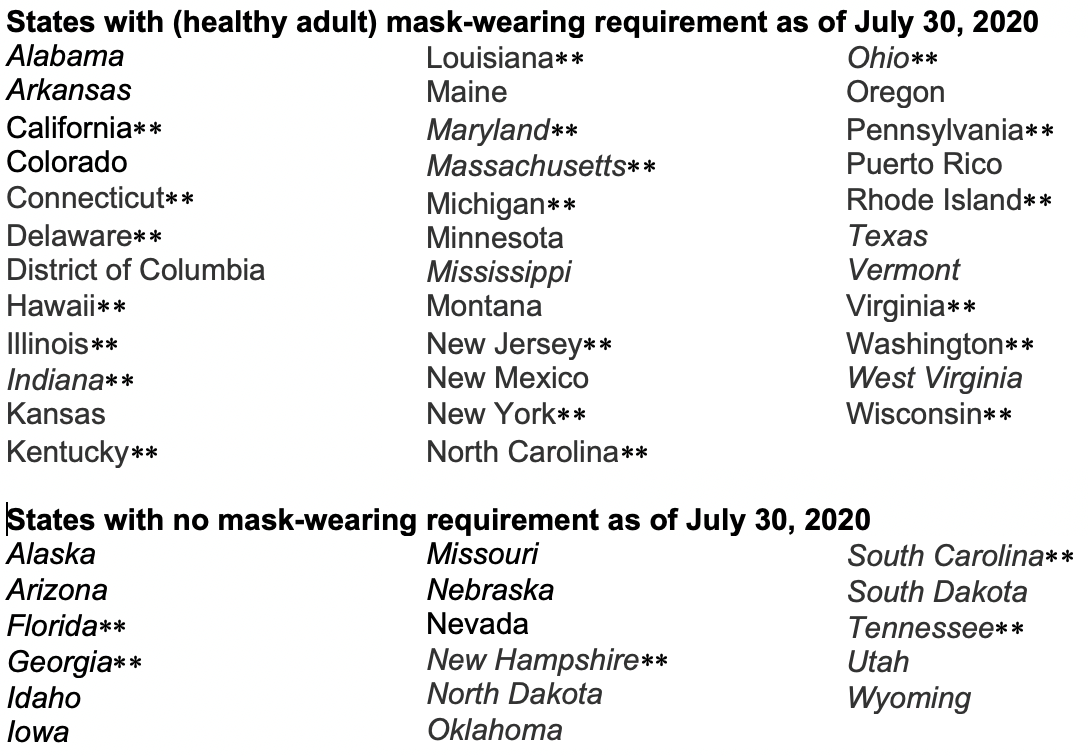

One viral mitigation policy that spurred intense political debate was mandatory mask-wearing requirements, which we show in Figure 2. Although the CDC advised that masks are effective in mitigating the viral spread in early April (CDC.gov 2020b), mask mandates were quickly politicized, with adherents and opposition coinciding neatly with partisan affiliation (Pew Research Center 2020). Opponents to mask-wearing ordinances claim that these measures are an unconstitutional restriction on freedom, and President Trump expressed ambivalence: “you can do it. You don’t have to do it. I am choosing not to do it. It may be good. It is only a recommendation” (Lizza and Lippman 2020). Again, this complacency further undermined state and local governmental efforts to normalize mask-wearing, and publicly disincentivized compliance with mask-wearing rules.

Figure 2. Mask Mandates by State

Italicized state names Republican governors. **Denotes states above the median of population density. Puerto Rico and Washington DC are unranked by population density.

As shown in Figure 2, an absolute majority of states and territories adopted mask mandates. The role of population density is an evident factor at play: sparsely populated states such as Alaska and Wyoming declined to impose restrictive mask-wearing rules, whereas densely populated states (Hawaii) and states of major metropolitan areas (New York) imposed some of the strictest measures. Yet a clear pattern of partisanship also emerges, reflecting the politicized nature of the mask-wearing recommendations. Of the twenty-six states with Republican governors, only 38% (10) would adopt statewide mandates for mask wearing; amongst non-Republican states and territories, 96% of them required masks. Indeed, of the 17 states that declined to adopt a mask-wearing requirement, only Nevada was led by a Democratic governor.

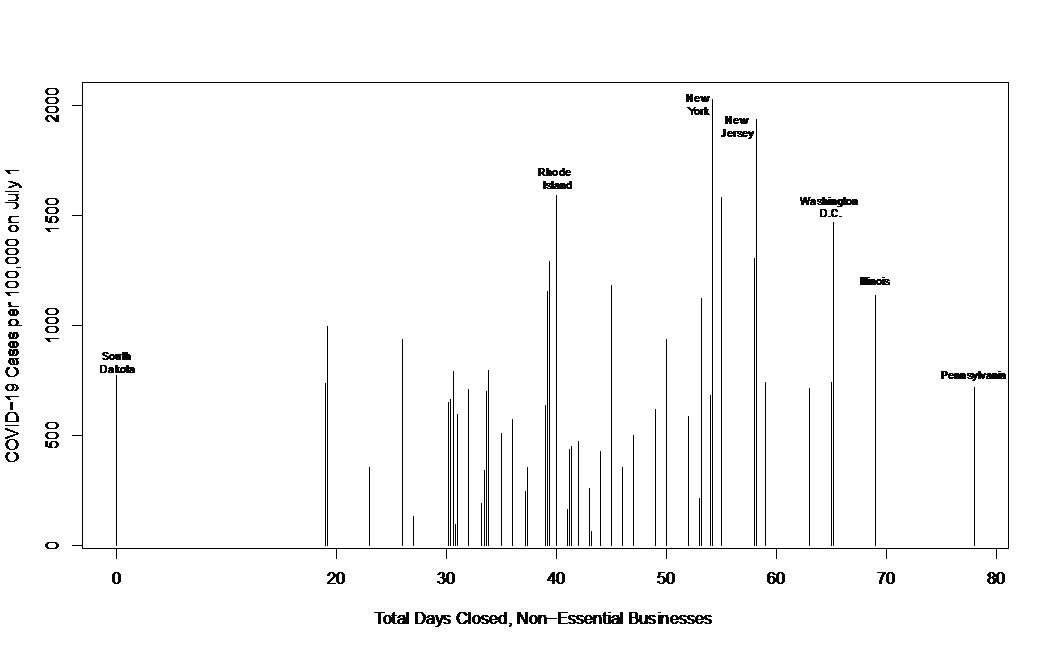

We now examine one possible measure of effectiveness of COVID-19 restrictions to consider the closure of non-essential businesses across states (see Figure 3).[5] The x-axis represents non-essential business closures in days, while the y-axis represents the number of state reported COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people on July 1 (Johns Hopkins CSSE COVID-19 2020).[6] Non-essential business closures ranged from twenty to eighty days. An exception is South Dakota, which never officially closed. States with the lowest case counts are Hawaii, Montana, and Alaska, whose businesses were closed for 43, 30, and 27 days, respectively. States with the highest case rates include Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. With the exception of California, Florida, and Massachusetts, these states are home to some of the largest – and most densely populated – urban centers.

Figure 3. COVID-19 Cases Per 100K on July 1, by Days of Non-Essential Business Closure

There are several interesting trends of note from Figure 3. First, the bivariate relationship between non-essential business closure and case count shows a modest, albeit positive correlation (r = 0.25). This implies that those states that were shut down the longest also saw the highest rates of infection come July 1. This is unsurprising given the states with the longest duration of shutdowns are also those with major urban centers. Relatedly, the correlation between population density and case count is a positive, but still modest, r=0.35. Finally, when we remove the ten greatest outlier states from our data, the correlation is r=-0.09, which is statistically indifferentiable from zero. This correlation would imply that for the 40 ‘typical’ states, longer shutdowns may have yielded a reduction in the infection rate. This is only conjecture, and if it were true the effect would be minor.

Critically however, with only bivariate correlations, we cannot draw causal conclusions, and the weak correlations we do find demand even more inferential restraint. We do not control for confounding variables, including those that would be critical in explaining incident rates, such as population density (which impacts transmissibility) or breadth and accuracy of testing (which impacts detection). These caveats aside, the relatively weak nature of our correlations point to two potential conclusions. First, whereas the states that closed the longest are also home to populations where transmission was more readily spread (due to high population density), then our weak correlations might indicate the successful mitigation of COVID-19: in these densely populated states and areas, case counts could have been far worse were it not for the state mandates to limit public interaction.[7] Second, our weak correlations might suggest that the states are too diverse to adopt a standardized approach to non-essential business closures and related mitigation strategies. Future research will no doubt interrogate these possibilities in more depth.

-

Conclusion

Our case study of the ‘ever so less’ United States illustrates the intrinsic tensions federalism implies. The pandemic related crises have given states an opportunity to enhance their expertise and innovation through the policymaking process. States have also been empowered to tailor their policies to regionalized – or localized – needs, and deftly shift course when local exigencies required a change. However, this decentralization in times of crisis also illustrates the “price of federalism,” with states offering their citizens very different solutions to the COVID-19 crises, worsening many economic and racial inequalities that predated the pandemic era (Petersen 1995). In other words, the way political leaders approach federalism in times of crises has critical consequences on citizen’s life. The coronavirus pandemic in the US illustrates this point, where hundreds of thousands lives depend on decisions to centralize or delegate power. Future research should continue to scrutinize these trends, to better understand the trade-offs that federalism necessarily entails, and how the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped American federalism in the years to come.

Achenbach, Joel, and Laura Meckler. 2020. “Shutdowns prevented 60 million coronavirus infections in the U.S., study finds.” Washington Post. June 8, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/06/08/shutdowns-prevented-60-million-coronavirus-infections-us-study-finds/. [Accessed 11 November]

Artiles, Alexandra, Martin Gandur, and Amanda Driscoll. 2020. “The (Less) United States: Federalism & Decentralization in the Era of COVID-19.” In Federalism in Times of COVID- 19: A Comparative Perspective, ed, Esteban Nader. Washington, DC: Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020a. “Cases in the U.S.” CDC.gov, 9 October, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020b.“Mask Wearing Evaluation.” CDC.gov, 18 August, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/mask-evaluation.html. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Cohen, John. 2020. “The United States badly bungled coronavirus testing – but things may soon improve.” ScienceMag.org, 28 February, 2020. Available at https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/united-states-badly-bungled-coronavirus-testing-things-may-soon-improve. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Coleman, Justine. 2020. “All 50 States Under Disaster Declaration for the First Time in US History.” The Hill, 12 April, 2020. Available at https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/public-global-health/492433-all-50-states-under-disaster-declaration-for-first. [Accessed 4 October]

Cook, Nancy and Dan Diamond. 2020. “ ‘A Darwinian Approach to Federalism’: states confront new reality under Trump,” Politico.com, 31 March, 2020. Available at https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/31/governors-trump-coronavirus-156875. [Accessed 24 September 2020]

Glasser, Susan B. 2020. “Bob Woodward Finally Got Trump to Tell the Truth About COVID-19.” NewYorker.com, 11 September, 2020. Available at https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-trumps-washington/bob-woodward-finally-got-trump-to-tell-the-truth-about-covid-19. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Hsiang, Solomon, Daniel Allen, Sébastien Annan-Phan, Kendon Bell, Ian Bolliger, Trinetta Chong, Hannah Druckenmiller, Luna Yue Huang, Andrew Hultgren, Emma Krasovich, Peiley Lau, Jaecheol Lee, Esther Rolf, Jeanette Tseng & Tiffany Wu. 2020. “The Effect of Large-Scale Anti-Contagion Policies on the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Nature. 8 June, 2020. Available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2404-8.[Accessed 3 November].

Ingraham, Christopher. 2020. “A Powerful Argument for Wearing a Mask, in Visual Form,” The Washington Post, 23 October, 2020. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/10/23/pandemic-data-chart-masks/. [Accessed 24 October].

Johns Hopkins University. 2020. COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins University. Available at https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19. [Accessed 15 September]

Kiefer, Len. 2020. “US Labor Market Update: The U.S. Labor Market Turns Down.” Len Keifer: Helping People Understand the Economy, Housing and Mortgage Markets. 4 April, 2020. Available at http://lenkiefer.com/2020/04/03/us-labor-market-update-april-2020/. [Accessed 9 October]

Kincaid, John. 2018. “Dynamic De/Centralization in the United States: 1790-2010.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 49(1): 166-193.

Liptak, Kevin, Kristen Holmes, and Ryan Nobles. 2020. “Trump completes reversal, telling governors ‘you are going to call your own shots’ and distributes new guidelines.” CNN.com, 16 April, 2020. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/16/politics/donald-trump-reopening-guidelines-coronavirus/index.html. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Lizza, Ryan and Daniel Lippman. 2020. “Wearing a mask is for smug liberals. Refusing to is for reckless Republicans.” Politico.com, 1 May, 2020. Available at https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/01/masks-politics-coronavirus-227765. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Pew Research Center. 2020. “Republicans, Democrats Move Even Further Apart in Coronavirus Concerns.” Pewresearch.org, 25 June, 2020. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/06/25/republicans-democrats-move-even-further-apart-in-coronavirus-concerns/. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Raifman, Julia and Kristen Nocka, David Johnes, Jacob Bor, Sarah Lipson, Jonathan Jay, Megan Cole, Noa Krawczyk, Philip Chan, Sandro Galea. 2020. COVID-19 US State Policy Database. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2020-9-15. https://doi.org/10.3886/E119446V30

Schwellenbach, Nick. 2020. “The First 100 Days of the U.S. Government’s COVID-19 Response.” www.pogo.org, 6 May, 2020. Available at https://www.pogo.org/analysis/2020/05/the-first-100-days-of-the-u-s-governments-covid-19-response/. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Wamsley, Laurel. 2020. “Gov. Says Florida’s Unemployment System Was Designed to Create ‘Pointless Roadblocks’”, National Public Radio (NPR.com), 6 August 2020. Available at https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/08/06/899893368/gov-says-floridas-unemployment-system-was-designed-to-create-pointless-roadblock. [Accessed 3 October]

[1] Consider Simpson County Kentucky, and Robertson County, Tennessee, who share a border along the state line. As of July 31, Simpson County reported 236 cases and 7 deaths, while Robertson County had 8 times as many cases (1,942) and four times the number of deaths (29) (CDC 2020a).

[2] For a more in-depth review, please see our full article, available at https://bit.ly/3l5jqkL.

[3] The tide has since turned. As of October 2020, states with the highest rate of COVID-19 cases are those sparsely populated in the Midwest, including North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska, with the incident rates far exceeding the rates witnessed in COVID-19 hotspots throughout the summer (New York Times 2020).

[4] This is not to say all efforts were effective. One high profile failure played out in Florida, whose faulty unemployment website was so prone to malfunction that by April 20 only 6% of applicants had received benefits. It was later revealed this malfunction was intentional: reforms of the online system under former Governor Scott were designed to make it difficult to apply for benefits, such that the incumbent could report low unemployment numbers during his administration (Wamsley 2020).

[5] We consider the closure of non-essential businesses because the timing and length of time the states imposed this policy varies considerably across the states. Our conclusions are unchanged if we instead use bar and restaurant closures. Please see Raifman et al, (2020) for alternative measures.

[6] Whereas most states moved to shut down non-essential businesses the end of March and the first few days of April, July 1 represents the COVID-19 infection rate roughly three months after these measures were adopted. This is also approximately three weeks after the last state (Pennsylvania) lifted the prohibition, on June 5, 2020.

[7] For instance, researchers estimate that large-scale anti-contagion policies have prevented 60 million COVID-19 infections in the U.S. (Hsiang et. al 2020). See also Achenbach and Meckler (2020), and Ingraham (2020).

Share this post:

Collectivism and populism in the era of antivax (1)

October 2, 2020

Paulo Boggio and Carolina Botelho

In the midst of the greatest pandemic of our generation, many scientists are working hard to find a vaccine. Only with mass vaccination will it be possible to achieve the so-called collective immunity. However, some people argue that individuals should be free to decide whether or not they want to be vaccinated. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro said: “no one can force anyone to be vaccinated” and his government’s communications department published an advertisement with the words “the government of Brazil values the freedom of Brazilians.” Unfortunately, this kind of message finds resonance in part of the population. A study by Amin, Bednarczyk, Melchiori, Graham, Huntsinger, and Omer (2017) showed that liberty is a highly valued moral foundation in people with an anti-vaccine perspective. In this article, we discuss how moral foundations can influence adherence to vaccination and how vaccination campaigns can improve their communication. This discussion will be illustrated with the current Brazilian scenario since it is one of the countries that leads the world in the number of cases and deaths by COVID19.

After spending months denying the seriousness of COVID-19 and producing with public resources a medication tested and proven ineffective against the disease, President Bolsonaro strategically starts a new controversy: liberty would be above vaccination. We use the word strategy because any action or speech by an official authority has a public nature, therefore, interested in sending some type of public message.

This message starts to resonate and gain momentum in the public debate in Brazil. One of the central elements of the message is the idea of preserving and guaranteeing individual liberty. The concern with freedom related to vaccination is not exclusive to Brazilians. In fact, these ideas did not come from here. They are part of a process that takes place in various parts of the world and challenge modern societies based on scientific knowledge. This type of thinking rests on an idea of the so-called anti-vax, groups opposed to the mass vaccination of the population. Among other reasons, there is the assumption that groups of individuals can deny being vaccinated because they believe that compulsory immunization would restrict their individual freedoms. After all, who would like to have their liberty curtailed?

Amin, Bednarczyk, Melchiori, Graham, Huntsinger, and Omer (2017) captured this relationship between people opposed to mass vaccination and the greater concern for liberty (and also purity). The authors departed from Graham and Haidt’s model of moral foundations that describes morality in the following domains: Care, Authority, Purity, Justice, Loyalty, and Liberty. By common sense, we tend to think that care would be the moral foundation that guides people’s decisions towards greater support for the population’s vaccination. As a result, many campaigns emphasize health people’s care in their messages. However, what this study has captured is that the moral foundations of Liberty and Purity weigh far more in the choices. Some politicians seem to have picked up on that idea and have put much emphasis on this liberty in their messages.

When we hear from Brazilian government officials, like the president himself and his vice president, phrases like “no one can force anyone to be vaccinated” and “there is no way the government – unless we live in a dictatorship – force everyone to get vaccinated”, shows that these leaders saw fertile ground for a new populist enterprise. But why call populist the arguments that defend liberty? Because it is an argument built on a false premise and which aims to strengthen the President’s popularity and not exactly the Liberty of people. This type of public pronouncement by national leaders legitimizes individualistic behavior using the false premise of individual freedom, when in reality collective freedom suffers restriction and risks. The argument of the individual over the collectivity implies the fragile control of diseases – see the reappearance of diseases that humanity had already eradicated. It is the collective effort that will guarantee the full exercise of freedom.

Collective efforts can be seen around the world. Bureaucracies and governments have been organized in a way to reduce the damage caused by infectious diseases. Recently, WHO (World Health Organization) announced the eradication of polio in Angola. An excellent achievement for humanity. Just like the Angolan example, the world has evolved with public policies aimed at reducing diseases and their damage to their populations. All this effort reveals the action of governments to provide health policies to the population. In the case of the new coronavirus, several research centers in the world have announced successful responses in the development of vaccines capable of containing it, making it possible for one or a few to appear soon. National and international governments and health authorities, in turn, are organizing themselves to enable the distribution of immunizers on a global scale, with a view to the possibility of successful research. It is this global and collective effort that will allow us to get out of this pandemic.

There is an extensive literature that addresses the emergence of health policies in modern societies. Sociologist Abram de Swaan developed important research in which he dealt with the production of collective goods in different countries in Europe and in the United States. Epidemics would have, in their findings, privileged spaces for elites to organize themselves in favor of the collectivization of services aimed at fighting the virus. The reasoning is simple: for fear of being affected by contamination, and consequently having damaged business and ultimately becoming ill, the various groups of elites come together financially and structurally to bring the solution to everyone, including, of course, their own. We are watching this happen in the world. In many, many decades of history, we have not seen so many groups, so many institutions and nations strive to find the immunizer that fights COVID-19.

Since it first appeared in the city of Wuhan, China, the COVID-19 virus has quickly become pandemic due to its transmission capacity. The virus traveled across the globe in less than four months, leaving a trail of problems in the health systems, economy, and politics of several nations. The virus has caused problems in almost all affected countries and the year 2020 has been a challenge of enormous proportions for national leaders who are looking for ways out to fight the pandemic. The main problems encountered were the sharp fall in the countries’ GDP, rising unemployment, growth in government spending, and historic pressure on public and private health systems. However, countries whose government responses to the pandemic were fast showed less damage and less severity than those with a slow response or who denied the severity of the virus. The latter not only made the crisis worse but much longer. Let’s look again at Brazil.

Brazil is among the first countries with the highest death toll. And it’s not over yet. Its GDP decreased by 10% and for the first time in history, Brazil has more than 50% of the formal and informal workforce unemployed. In addition, in almost six months of an uncontrolled pandemic, Brazil has reached the devastating mark of more than 132 thousand deaths. After months of average daily deaths of around a thousand people, only now is there a reduction compatible with the deceleration of contamination.

The unprecedented situation of COVID-19 in Brazil added to the speeches of public authorities such as the president and his vice president show a serious situation in the country, i.e. the disease itself is not the only obstacle to be overcome – there is a behavioral challenge to be surpassed. The discussion on vaccination deserves to be extended beyond the epidemiological and health dimensions, but also those related to social and cultural values. The Brazilian Republican Constitution itself says that the public entity is obliged to vaccinate the population: “Law No. 13.979, of 6/6/2020 Art. 3 For coping with the emergency (…) the authorities may adopt (…): III-determination of mandatory performance of: d) vaccination and other prophylactic measures ”. The law is correct because it establishes the protection of the collective over the individualistic impulses or political maneuvers. Political leaders should foster collective actions: freedom is only guaranteed with the exercise of collectivity.

(1) Editor’s Note: This article was previously published in Behavioural and Social Sciences at Nature Research, Sep, 17, 2020.

References

Amin AB, Bednarczyk RA, Ray CE, et al. Association of moral values with vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1(12):873-880.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2013; 47: 55–130.

Swaan, Abram de. In Care Of The State. Health Care, Education And Welfare In Europe, And The USA In The Modern Era, Polity Press, 1988. 338 pp.

Share this post:

Sobre llovido, mojado: El impacto del coronavirus en el Chile post-estallido

August 20, 2020

Valeria Palanza y Magda Cottet

Antes de marzo de 2020 y de que comenzara la expansión del coronavirus en Chile, en el país la mayor preocupación era el levantamiento iniciado en octubre de 2019 y la situación política y social que lo motivaba. La movilización había disminuido en intensidad durante los meses del verano austral, pero prometía volver con toda su fuerza en marzo. La capacidad del gobierno para hacer frente a desafíos de orden público había sido puesta a prueba con vehemencia muy recientemente, las cifras de aprobación habían alcanzado niveles por debajo del 10% en febrero (CADEM, 2020) y es indudable que el manejo que han tenido de la crisis no ha podido escapar a la mirada crítica por parte de una sociedad en la que se instaló una desconfianza generalizada hacia el presidente, su gabinete y los otros poderes del Estado.

El avance de la crisis sanitaria en Chile y la respuesta del gobierno y la sociedad a ésta no podrían comprenderse sin referencia al levantamiento social y político de fines de 2019 y la desconfianza generalizada de la sociedad chilena hacia el sistema político y sus instituciones. Una de las principales críticas a la gestión del gobierno ha sido la falta de transparencia, presente desde los inicios hasta el presente, problema que no es exclusivo de Chile, pero donde reviste especial peso debido al marcado descenso de confianza en el gobierno. Vinculado a lo mismo, la gestión de la crisis sanitaria también ha estado signada por la relativa ausencia del presidente Piñera, comparado con el protagonismo de otros primeros mandatarios de la región. Pero precisamente debido al momento político de fondo que vive Chile, que no se ha interrumpido por el paso del virus, es que la coyuntura ha marcado de facto un cambio en el locus del poder político y el marcado fortalecimiento del congreso, lo que se debe festejar en el contexto hiper-presidencialista de Chile.

El 3 de marzo se confirmó en el país la primera persona contagiada por el virus, el primer fallecimiento se produjo el 21 de marzo. Desde entonces el país pasó de una reacción inicial oportuna, a un período de paulatino aumento de contagios (al 30 de abril el país registraba 16.023 contagios verificados y 227 fallecimientos) y cuestionamientos desoídos. Siguió una fase de caída libre que colocó a Chile durante semanas como el país con mayor cantidad de muertes normalizadas por población del mundo. En agosto el país vive una lenta pero cierta recuperación que se vive con cautela.

En una región donde los ejecutivos suelen concentrar prerrogativas en la figura del presidente, Chile sobresale por los amplios poderes impartidos por la Constitución al presidente para legislar y actuar de manera unilateral (Siavelis 1997, Alemán y Navia 2009). A pesar de esta concentración de poderes constitucionales, se ha extendido la noción de que la presidencia chilena ha utilizado con moderación sus atribuciones (Siavelis 2020, 2010), lo que también ha sido disputado señalando que la aparente moderación es resultado de una institucionalidad que restringe el rango de acción del legislativo al punto que el presidente no necesita salirse de su curso para resguardar sus preferencias (Palanza y Espinoza 2017).

La pandemia generada por el virus SARS-COV2 presenta un escenario propicio tanto para analizar de qué manera distintos países han hecho frente a la crisis sanitaria internacional como para observar el modus operandi de cada gobierno. Es lógico que en momentos de urgencia sanitaria las autoridades hagan uso de cuanta herramienta tengan a su alcance para dar soluciones rápidas a los desafíos especiales que enfrenta la población. Aún así, la capacidad de cada gobierno de sostener espacios de deliberación, procesar las opiniones de expertos y hacer frente a necesidades diagnosticadas en terreno son factores que aportan eficacia a esas decisiones, por lo que se repasarán brevemente las instancias utilizadas en Chile.

Así, en esta nota resumimos la línea de sucesos durante los meses de presencia del COVID-19 en Chile y analizamos las herramientas usadas por el gobierno de Chile para tomar medidas y hacer frente al riesgo sanitario. Analizamos en qué medida el congreso y otros actores políticos y sociales han participado de la respuesta que el gobierno ha generado. La nota argumenta que la crisis sanitaria, cuyo arribo a Chile se produjo en un contexto social saturado de desconfianza y acrimonia hacia el gobierno desde octubre, ha puesto al rojo vivo las confrontaciones políticas que ya venían decantando en el país en los últimos años, y que el levantamiento de fines del 2019 aceleró. Así, en retrospectiva resulta impactante la intervención que ha tenido el congreso, constitucionalmente limitado en sus funciones y hasta ahora relativamente pasivo frente a dicha limitación. Desde el congreso se han movilizado medidas urgentes que la presidencia no atinó a impulsar, dando testimonio, con sus actos, que las asambleas colectivas sí consiguen coordinar y hacer frente a desafíos presentados en emergencias nacionales.

Primera Etapa: Optimismo Desconectado

Ante el avance de la pandemia y las recomendaciones de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), el 18 de marzo el ejecutivo declaró el Estado de Catástrofe, uno de los cuatro estados de excepción que prevé la Constitución chilena para hacer frente a situaciones de conmoción pública. Los estados de excepción en Chile son regulados por la Ley Orgánica Constitucional de los Estados de Excepción, (aprobada en 1985, durante el gobierno de Pinochet). En esta oportunidad, la declaración se hizo por 90 días, permitiéndose que la ley sea renovada por igual tiempo, pero con aprobación del congreso, si subsisten las condiciones que dieron lugar a la declaración. El Estado de Catástrofe entró en vigencia el 19 de marzo.

La declaración del Estado de Catástrofe es importante por diversos motivos, ya que mediante esta declaración se establece la posibilidad de restringir reuniones en espacios públicos, además de medidas tendientes a asegurar la provisión de bienes y servicios básicos, establecer cuarentenas y toques de queda, y limitar el tránsito de personas. El Estado de Excepción Constitucional abrió las puertas para pedir a las Fuerzas Armadas su colaboración y la designación de Jefes de Defensa Nacional para asumir el mando de las Fuerzas de Orden y Seguridad Pública en las zonas respectivas. También, y de gran importancia, la declaración habilitó al Ejecutivo a decretar pagos no autorizados por ley hasta un monto equivalente al 2% del monto de gastos autorizados en la Ley de Presupuestos (artículo 32 inciso 20 de la Constitución), lo que cobra especial urgencia en una situación de urgencia sanitaria. De inmediato se estableció, el 22 de marzo, un toque de queda nocturno, medida que reavivó temores por el uso indebido de la fuerza pública que se produjo durante los levantamientos de octubre, aún cuando esta vez cumpliera el fin de evitar la propagación y evolución de la pandemia[1]. Asimismo, la reasignación de presupuesto fue usada, por ejemplo, en la Ley 21.225 que establece medidas para apoyar a las familias y a las micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas por el impacto del covid-19 en Chile, publicada el 2 de abril (e iniciada mediante proyecto del ejecutivo el 20 de marzo de 2020).

Desde el principio y hasta la fecha, la principal estrategia de Chile para hacer frente al contagio y expansión de la enfermedad en el país ha estado definida por una política de cuarentenas móviles, a través de la evaluación semanal de contagios y fallecimientos por comuna. Así, una semana después de haberse declarado el Estado de Catástrofe, el 25 de marzo, el Ministerio de Salud anunció que siete comunas de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago serían puestas en cuarentena. En un contexto como el señalado, en que la desconfianza atraviesa a la sociedad chilena, esta política enfocada en comunas pareció acentuar diferencias socioeconómicas preexistentes, y marcó un inicio turbulento para la implementación de la política.

De inmediato, el Congreso aprobó una enmienda a la constitución para permitir que el legislativo funcionara de manera remota. La enmienda introdujo la disposición transitoria 32ª que habilita al congreso a funcionar por medios telemáticos una vez declarada una cuarentena sanitaria o un estado de excepción constitucional que les impida sesionar, y mientras este impedimento subsista. El procedimiento telemático debe asegurar que el voto de los parlamentarios sea personal e indelegable, y permite “… sesionar, votar proyectos de ley y de reforma constitucional y ejercer sus facultades exclusivas.” Mediante el acuerdo de los comités que representen a dos tercios de los integrantes de cada cámara se pasó a funcionar de manera remota. De manera que las medidas propuestas por el gobierno han sido encaminadas al congreso para su aprobación mediante los canales legislativos regulares.

El paquete de medidas desarrollado por el gobierno no ha estado exento de controversia, en alguna medida por deficiencias y desaciertos comunicacionales propios de esta administración presidencial. La modalidad en que la cuarentena ha sido aplicada en Chile fue denominada por el entonces Ministro de Salud Jaime Mañalich como “estratégica y dinámica”, a diferencia de cuarentenas totales o “verticales” usadas en otros países. Desde que las primeras siete comunas fueron puestas en cuarentena a fines de marzo, diversas comunas han ingresado y salido de la cuarentena, algunas ingresando solo cierta porción de la comuna y otras reingresando después de un período de levantamiento de esta. Las cuarentenas fueron acompañadas por aduanas sanitarias desde las cuales se realizan controles de salud y de cumplimiento de la cuarentena.

En el inicio, aún cuando el Ministerio de Salud había señalado los factores tomados en cuenta a la hora de decidir el ingreso o egreso de una comuna a la cuarentena, fue duramente criticada la falta de transparencia en la comunicación del criterio usado, dado que no había sido explicitada la manera en que los factores tomados en cuenta incidían, ni cuáles eran las fuentes de los indicadores usados para el cálculo sobre el que se basa la decisión. Bajo el liderazgo del Ministro Mañalich, el Ministerio de Salud se demoró en poner el criterio por escrito, y en distintas oportunidades comunicó a la población cosas diversas e información difusa (La Tercera, 1-abr-20; La Segunda, 13-ago-20). En un primer momento, el Ministerio de Salud explicó que el criterio para decidir qué comunas entran a la cuarentena estaba dado por la tasa de contagio (aquellas que tuvieran 40 casos por 100 mil habitantes). Pronto se hizo evidente la existencia de comunas que cumplían ese criterio sin estar en cuarentena (Litoralpress, 10-abri-20). El 2 de abril la vocera de gobierno Karla Rubilar instaló mayores dudas cuando explicó que “no hay un solo criterio, es importante transmitir que es muy relevante saber cuánto es la cantidad de contagio por cantidad de habitantes en cada comuna, pero también tenemos que mirar la cantidad de contagios por kilómetro cuadrado de esa comuna” y a eso agregó un listado de variables: dónde están ubicados los contagios, su nivel de concentración al interior de una comuna, nivel de vulnerabilidad de la población, si hay adultos mayores o población migrante, o población flotante, variables geográficas como la accesibilidad de la localidad, y la capacidad de respuesta del sistema de salud en la localidad.

El cuestionamiento respondía a distintas líneas y no es independiente de la fuerte desconfianza instalada en una sociedad que muy recientemente se movilizó al punto de paralizar al país. Que entre las primeras siete comunas puestas en cuarentena (Independencia, Las Condes, La Reina, Lo Barnechea, Ñuñoa, Providencia y Vitacura) se encontraran las comunas más ricas del país, que coincidían con las de residencia de buena parte de la élite económica y política del país, avivó desconfianzas fruto del contexto político y social antes que de motivos técnicos asentados. A medida que avanzó el contagio en el país el ingreso y egreso de comunas a cuarentena fue diversificándose y disipando las dudas iniciales.

Aún así, los desaciertos del gobierno en los primeros tres meses permitían predecir lo que seguiría: el gobierno no declaró la cuarentena en la región completa de Santiago, el mayor centro urbano del país sino hasta el 15 de mayo, tras registrarse 2660 nuevos contagios (aumento del 60% de casos en un solo día) y tras llevar el país 10 días de alza sostenida de casos críticos (BBC, 14/Jun/20). Antes de eso, a fines de abril, el Ministerio había comenzado a gestar un retorno a una “nueva normalidad”, en señal de desconocimiento de la realidad de avance del virus en comunas con niveles importantes de hacinamiento, lo que debió ser una preocupación del gobierno desde temprano.

Los principales actores detrás de las duras críticas al accionar del gobierno han sido principalmente alcaldes y alcaldesas de todo el espectro político, incluido el del gobierno, y fuertemente el Colegio Médico. Desde temprano estos actores plantearon su disconformidad con el hermetismo con el que el gobierno tomaba decisiones para hacer frente a la pandemia. Para hacer frente a críticas provenientes de diversos sectores y con el objetivo expreso de incorporar opiniones de diversos actores a la toma de decisiones, el 22 de marzo el gobierno convocó a una Mesa Social, en la que además de contar con la presencia del Ejecutivo, se dio participación a asociaciones de municipalidades (Asociación Chilena de Municipalidades, Asociación de Municipios de Chile y Asociación de Municipios Rurales), a los rectores de algunas universidades importantes (Universidad de Chile, Universidad Católica y Universidad de Santiago de Chile), al Colegio Médico (representado por su presidenta, Izkia Siches), ex ministros de salud y a representantes de la Organización Mundial de la Salud en Chile. No obstante, el ejecutivo también se ocupó de recalcar el carácter consultivo de la mesa, resguardando la posibilidad de aceptar o no las recomendaciones, por lo que se ha mantenido una fuerte confrontación entre ediles, médicos-as y el presidente, al menos hasta el cambio de Gabinete que reemplazó al Ministro de Salud Mañalich por el actual Ministro Enrique Paris, cuya designación incluyó un guiño hacia sectores críticos, fundamentalmente el Colegio Médico, organismo que el nuevo ministro presidió por dos períodos entre 2011-2017.

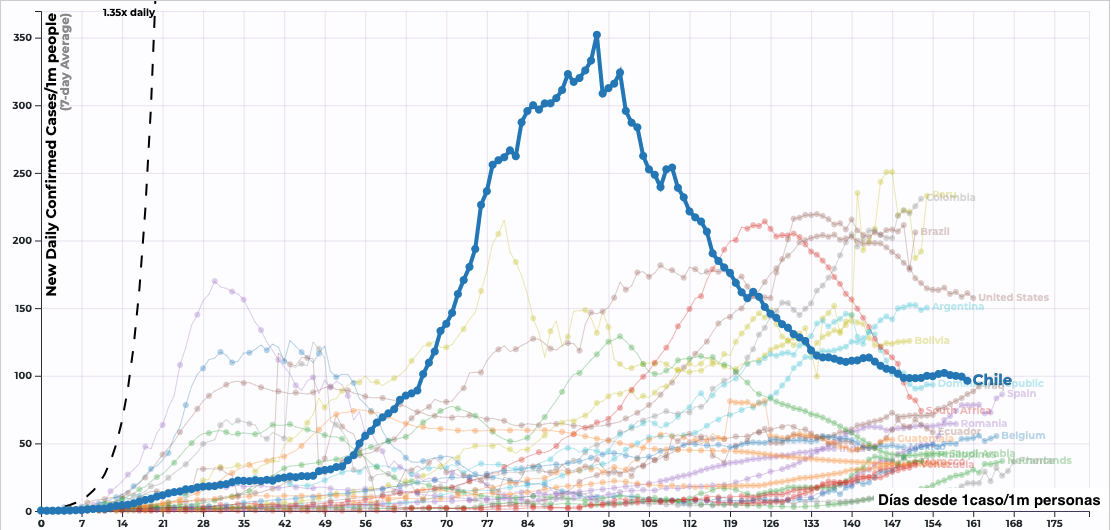

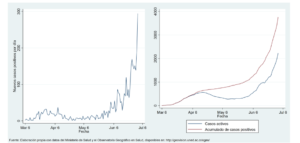

Segunda Etapa: Caída Libre y Recambio

El cambio de gabinete que trajo al Ministro de Salud Paris al mando llegó en medio del peor momento vivido hasta ahora en términos de contagio y fallecimientos. El gráfico 1 muestra la evolución de nuevos casos por millón de personas, y el desarrollo excepcional de Chile en esta evolución. Durante los primeros 40 días de presencia del coronavirus en el país se podría decir que el aumento de contagios avanzó de manera relativamente moderada. Quizás allí estén las raíces del optimismo inicial, que cantó victoria de modo apresurado y promovió el retoro a la nueva normalidad. Entre los 45 y los 60 días de evolución del virus en el país se puede observar el despegue exponencial de los contagios. Esta tendencia creciente se mantuvo durante aproximadamente 30 días, con un lamentable saldo de muertes, y una aparente incapacidad del gobierno de hacer frente tanto a la crisis sanitaria en sí misma, como a la crisis económica desencadenada por la sanitaria. El gobierno no supo medir las consecuencias de la cuarentena en las posibilidades de las familias de hacer frente a sus necesidades básicas, y la imperiosa necesidad de quebrar la cuarentena como consecuencia. A esto se han referido oposición política y medios de comunicación como la desconexión del gobierno con la realidad de las personas de ingresos medios y bajos.

El plan ideado por el gobierno para hacer llegar alimentos a las familias por medio de cajas con alimentos empaquetadas y distribuidas de manera centralizada por la presidencia, constaba de tales fallas logísticas que el propio gobierno anunció que demoraría dos meses en completar la entrega a todos los hogares. Así, la crisis por la paralización de actividades desencadenó necesidades económicas y de subsistencia básica que inevitablemente retroalimentaron la crisis sanitaria, junto al cada vez mayor desgaste de un gobierno ya anémico.

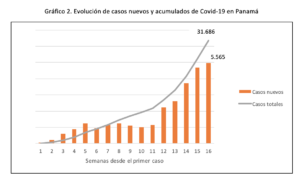

Gráfico 1. Casos nuevos de COVID-19 confirmados por día,normalizados por población

Fuente: Gráfico producido por 91-divoc.com[2], datos de Johns Hopkins University CSSE al 16-08-2020.

Quién ha legislado, qué se ha decidido

Además de lo descrito hasta aquí, nos interesa analizar en esta nota en qué medida el ejecutivo ha hecho uso de la crisis sanitaria para concentrar poder legislativo. Ya mencionamos que para hacer frente a las restricciones de reunión y movilidad, el congreso reaccionó de manera oportuna y mediante iniciativa presentada en el Senado, enmendó la Constitución para hacer posible su funcionamiento por medios telemáticos, permitiendo que ambas cámaras comenzaran a sesionar de inmediato. Dado que a partir del 15 de marzo tomó pública prioridad para el gobierno la cuestión del coronavirus, a continuación analizamos la legislación que se aprobó desde esa fecha y hasta el 14 de agosto.

En medio de la quietud y desaciertos del ejecutivo, se produjo lo inesperado en el Chile post-Pinochet: la activación del Congreso como órgano legislador y la superación de trabas políticas y constitucionales que habían mantenido al congreso al margen de iniciativas de peso. Tras una actitud inicial más pasiva, a medida que avanzó la crisis sanitaria en varias oportunidades el congreso pudo forzar la mano legislativa del ejecutivo al impulsar leyes que el sistema no le permitía avanzar debido al impedimento que tiene el congreso para disponer gasto, por ejemplo. En esta coyuntura el congreso se animó a legislar lo que el ejecutivo no, y a alentar medidas que simplemente no tenían el apoyo del presidente, pero que en el contexto social y político reinante hubiera sido muy costoso pelear para un presidente debilitado como Piñera. El ejemplo por antonomasia que ilustra lo anterior es el proyecto convertido en ley por el cual se permitió el retiro voluntario del 10% de los fondos de pensiones privados. El proyecto implicó un desafío abierto al ejecutivo y sectores de la coalición de gobierno prestaron su apoyo a un proyecto de oposición por naturaleza, permitiendo su aprobación a prueba de vetos, y marcando un quiebre difícil de superar para la ya resquebrajada coalición de derecha.

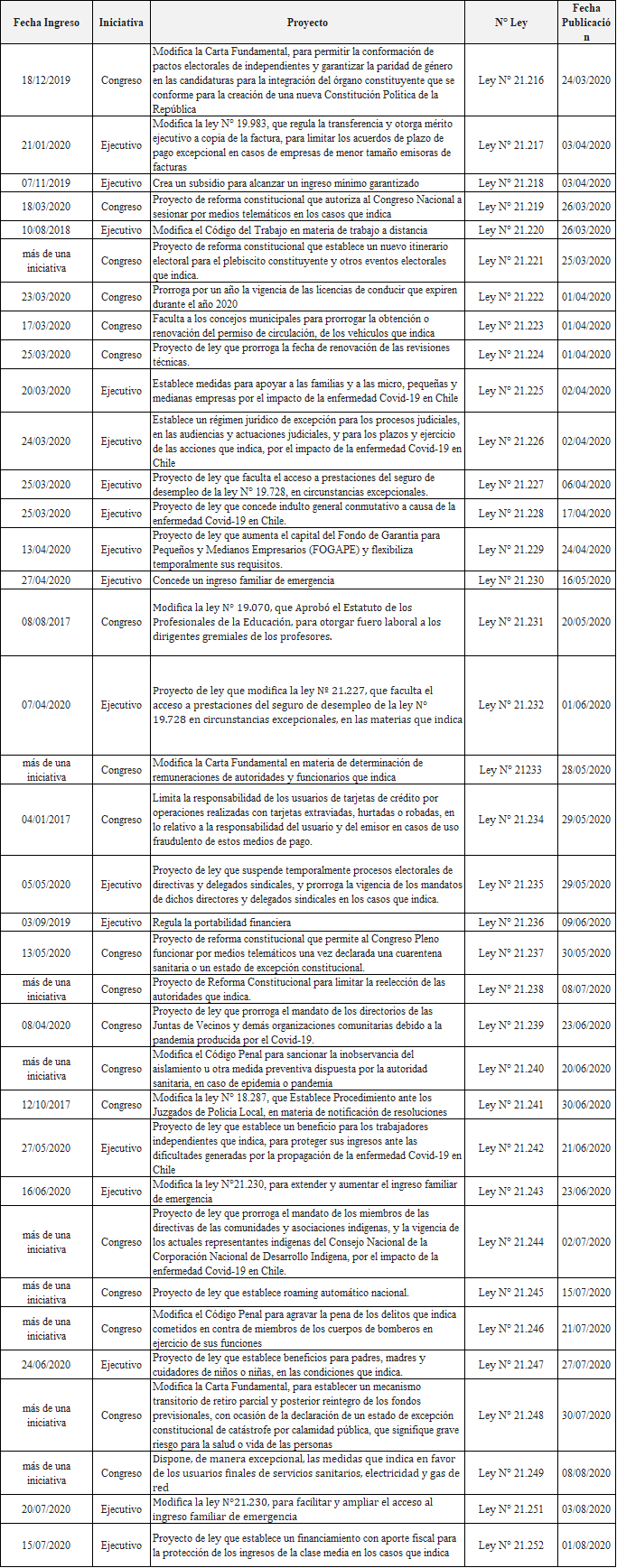

Son treinta y seis las leyes publicadas en el período, diecisiete de iniciativa congresional y diecinueve de iniciativa del ejecutivo, todas de relevancia para la coyuntura planteada por la pandemia. De los proyectos iniciados por el ejecutivo, la mayoría fueron iniciados en el período en cuestión y aprobados con la colaboración del congreso con toda celeridad. Las excepciones, en términos de proyectos que venían desde antes y cuya aprobación fue impulsada, estuvieron dadas (a) por el proyecto que modificó el Código del Trabajo en materia de trabajo a distancia, que databa de 2018 y debió ser aprobado con urgencia dada la relevancia que impuso la crisis a esta modalidad de trabajo, y (b) el proyecto de portabilidad financiera. Entre los proyectos iniciados por legisladores, destaca uno que venía de antes de la pandemia: el proyecto de ley de enmienda a la constitución para garantizar la paridad de género en las candidaturas para la integración del órgano constituyente –proyecto que es heredero de las negociaciones surgidas a partir de la crisis social y política generada por el estallido de octubre de 2019. A este proyecto se suman otros íntimamente ligados al momento de efervescencia política y definición constitucional, como ser la calendarización de eventos ligados al plebiscito, la rebaja salarial de legisladores y otros cargos altos, y las limitaciones impuestas a la reelección de determinados cargos.

Aún así, la mayor parte de los proyectos fueron iniciados a partir de marzo de 2020 a raíz de la crisis, para hacer frente a los desafíos asociados a aspectos sanitarios y económicos. De modo interesante, y dado el impedimento constitucional que tiene el Poder Legislativo en Chile para generar gasto, los proyectos iniciados por legisladores versan mayormente en los primeros meses de la crisis sanitaria sobre temas de derechos políticos (paridad de género en el órgano constituyente y calendario electoral) y sobre asuntos de impacto cierto pero marginal en la población, como la propuesta de posponer el vencimiento de validez de los permisos de circulación de automóviles que ser renuevan en marzo todos los años –dado que el cumplimiento de la renovación se vio complicado por la logística propia del distanciamiento social. El cambio en esta tendencia marca, a nuestro modo de ver, el fin de una era política en Chile, marcada por el resguardo del consenso necesario para sostener un modelo heredado de Pinochet.

Los proyectos iniciados por el Ejecutivo versan sobre asuntos centrales a la estrategia del gobierno para hacer frente a los desafíos planteados por la pandemia, y como es de esperar, menos en cuidar del proceso de plebiscito que surgió precisamente como acuerdo entre partidos ante protestas contra la gestión de Piñera. Tanto el proyecto iniciado meses atrás para legislar el trabajo a distancia, como los proyectos de apoyo económico a familias, a trabajadores de bajos ingresos, a las micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas, y las medidas tendientes a disminuir la población carcelaria en el tramo etario más alto, fueron propuestas del ejecutivo, tramitadas haciendo uso de la atribución de la urgencia legislativa (que la presidencia puede imponer a cualquier proyecto de ley).

Así, vemos que aún con estado de catástrofe declarado y en medio de la mayor crisis sanitaria, agravada por el trasfondo de fuerte confrontación política y social, la presidencia se ha mantenido a raya de gobernar por decreto, fiel a sus prácticas habituales. De modo interesante, el gobierno chileno ha resguardado las prerrogativas del congreso, aún fortaleciéndolas.

Legados Institucionales de la Crisis

Para dar cierre a este informe, quisiéramos destacar que si bien toda emergencia de salud pública requiere de la toma de decisiones rápidas, el caso de Chile ilustra que el congreso puede aportar al proceso y es capaz de deliberar y acordar medidas con la urgencia que las circunstancias requieren. Esta nota enfatiza que el coronavirus se hizo presente en Chile en medio de una crisis política profunda que impuso una agenda de reforma a las políticas sociales y a la constitución misma. El ánimo en las calles se encontraba enardecido por las consecuencias de décadas de políticas que sacaron a Chile de la pobreza pero dejaron un saldo de desigualdad que ha movilizado a la ciudadanía. Los levantamientos de octubre también dejaron al descubierto la inoperancia de las fuerzas policiales para garantizar la seguridad a la ciudadanía. El contexto de crisis económica que provoca la pandemia ejerce presión en el mismo ámbito que a fines de 2019 parecía no admitir más presiones, por lo que el desafío para el gobierno se ha visto multiplicado. A la preocupación por la situación sanitaria se suma la preocupación por el orden público y que el delicado equilibrio delineado pudiera romperse. Si bien las principales críticas al gobierno han sido formuladas por alcaldes y alcaldesas preocupados-as por la situación en sus comunas, el gobierno ha dirigido sus propios misiles a su oposición en el congreso y ha hecho uso de todas sus facultades legislativas para aportar, frenar o dirigir el debate, principalmente a nivel presupuestario, donde tempranamente se utilizó la facultad de hacer uso de un 2% presupuestario de manera unilateral y sin aprobación de otros órganos.

Es interesante observar que en este período las leyes aprobadas fueron iniciadas en partes iguales por el ejecutivo y el legislativo, lo que marca un cambio en la tendencia de predominio presidencial en la aprobación de leyes, sostenida desde los 90. Desde la reinstauración de la democracia en Chile, sólo un porcentaje menor de las leyes aprobadas, como máximo un tercio, solía ser iniciada por el congreso (Visconti, 2011). De la mano de los cambios que se vienen dando en el sistema político chileno, algunos de ellos plasmados en la reforma electoral de 2014, otros ocasionados por el ingreso de fuerzas nuevas al congreso como consecuencia de esa reforma, el congreso ha ido afirmando sus derechos políticos. El rol que desde el congreso han ocupado varios actores políticos a partir del levantamiento y durante la crisis sanitaria dan testimonio de este reajuste en el locus del poder.

Fuentes: www.bcn.cl/leychile/ y www.senado.cl

[1] A un mes de declarado el toque de queda, más de diez mil personas lo habrían infringido. Durante los primeros tres días tras su instauración se produjo la menor cantidad de infracciones, entre 212 y 248 casos. Posteriormente la cifra creció, llegando a superar en 5 oportunidades las 500 personas sólo durante el primer mes (El Mostrador, 17 de abril de 2020). Aún así, son pocos los casos de comportamiento inapropiado informados por los medios, aunque sí algunos han sido reportados (El Desconcierto, 19 de abril de 2020).

[2] Link directo con las opciones graficadas: https:–91-divoc.com-pages-covid-visualization-?chart=countries-normalized&highlight=Chile&show=25&y=both&scale=linear&data=cases-daily-7&data-source=jhu&xaxis=left#countries-normalized

Referencias

Ley Chile.

https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=29824

https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1143580&idParte=0

Litoralpress. 10-04-20. https://www.litoralpress.cl/sitio/Prensa_Texto?LPKey=WUwy5lvcY0Nckibx%C3%9C5ZMOSZqV6S9i37HbljU/lmX9dM%C3%96

Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile.

https:–www.minsal.cl-ministro-de-salud-anuncio-cuarentena-total-para-siete-comunas-de-la-rm-

https:–www.minsal.cl-nuevo-coronavirus-2019-ncov-

EMOL. 8-may-20. https:–www.emol.com-noticias-Nacional-2020-05-08-985540-Minsal-cuatro-criterios-cuarentena.html

La Tercera. 1-abr-20. https://www.latercera.com/nacional/noticia/que-parametros-toma-en-cuenta-la-autoridad-para-decretar-una-cuarentena/GH56PTEVYFDEROJMZXBRET6Y3A/

BBC. 14-jun-20. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-53037469

Visconti, Giancarlo. 2011. “Comportamiento Diacrónico del Congreso en Chile: ¿Crecimiento o estancamiento de su influencia?”, Revista de Ciencia Política, 31(1), 91-115. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-090X2011000100005

CADEM, 2020. Encuesta Plaza Pública No. 319, tercera semana de febrero https://www.cadem.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Track-PP-319-Febrero-S3-VF_Baja.pdf

El Mostrador. 17-abr-20. https:–www.elmostrador.cl-noticias-pais-2020-04-17-a-un-mes-del-inicio-del-toque-de-queda-nacional-carabineros-realiza-balance-mas-de-10-mil-personas-infringieron-la-medida-

Gobierno Digital, Gobierno de Chile. https:–cdn.digital.gob.cl-filer_public-d7-5e-d75e6460-0d18-4d50-9593-109d8ae8b7ef-declaracion_estado_de_catastrofe.pdf

El Desconcierto. 19-abr-20. https:–www.eldesconcierto.cl-2020-04-19-formalizan-a-seis-militares-por-apremios-ilegitimos-en-la-region-de-antofagasta-

Siavelis, P. 1997. “Executive-Legislative Relations in Post-Pinochet Chile: A Preliminary Assessment”, en Mainwaring, Scott y Matthew Shugart (eds.) Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America, Cambridge University Press

Mainwaring, S. y M. Shugart. 1997. (eds.) Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America, Cambridge University Press

Alemán, E. y P. Navia. 2009. Institutions and the legislative success of ‘strong’presidents: An analysis of government bills in Chile, The Journal of Legislative Studies, Vol 15 Issue 4, pp. 401-419

Palanza, V. y R. Espinoza. 2017. “El locus del Congreso en el sistema político chileno”, with Rodrigo Espinoza, in Juan Pablo Luna and Rodrigo Mardones (Eds.). La Columna Vertebral Fracturada: Revisitando Intermediarios Políticos en Chile. Santiago: RIL Editores

Siavelis, P. 2002. “Exaggerated presidentialism and moderate presidents: executive-legislative relations in Chile” Legislative Politics in Latin America No. 50, pp.79-113

Siavelis, P. 2010. President and congress in postauthoritarian Chile: Institutional constraints to democratic consolidation, Penn State Press

Share this post:

Cómo Uruguay Enfrentó la Pandemia del Coronavirus

August 6, 2020

Daniel Chasquetti

Los exitosos resultados de Uruguay en el combate a la pandemia fueron ampliamente destacados por diferentes organizaciones multilaterales y por los medidos de prensa internacional. El secreto del buen desempeño reside en la combinación de tres factores cruciales: estructuras institucionales sólidas, una estrategia de gobierno flexible y una consistente cultura cívica.

La llegada del coronavirus coincidió con la asunción de un nuevo gobierno. Cinco meses antes, en noviembre de 2019, el candidato de centro derecha del Partido Nacional, Luis Lacalle Pou, consiguió una apretada victoria en la segunda vuelta presidencial, generando la primera alternancia de partidos en el gobierno en quince años. El nuevo presidente diseñó un gobierno de coalición con el apoyo de cinco partidos que brindan una holgada mayoría legislativa en ambas cámaras. Si bien Uruguay no estaba inmerso en una crisis económica, el nuevo gobierno debía enfrentar algunos problemas serios como el estancamiento de su economía, la creciente inseguridad ciudadana, un déficit fiscal del 5% del PIB y un desempleo del 10%.

Cuando las nuevas autoridades comenzaban a asumir sus funciones, se conocieron los primeros cuatro casos de coronavirus en el país. Este suceso alteró la estrategia del gobierno de coalición y también la actitud del principal partido de oposición, el hasta ahora gobernante, Frente Amplio. A partir del 13 de marzo, el presidente impulsó una serie de medidas excepcionales que con el transcurso del tiempo darían muy buenos resultados. El gobierno tomó decisiones rápidas y drásticas que contaron con un amplio apoyo del sistema político y un acatamiento generalizado de una ciudadanía informada. En este texto se describe la forma en cómo Uruguay enfrentó al coronavirus en el primer semestre de 2020. En el primer apartado se repasa brevemente las fortalezas institucionales del país. En el segundo se describe la estrategia impulsada por el Presidente Lacalle Pou. En el tercero se muestra cómo evolucionó la pandemia y cómo el país comenzó a retornar a la normalidad. En el último apartado se reflexiona sobre los desafíos futuros.

Las fortalezas institucionales de Uruguay

El gobierno uruguayo enfrentó a la pandemia apoyado en un marco institucional sólido. La democracia uruguaya cuenta con tres características principales: i) un régimen presidencial atenuado; ii) un sistema de partidos institucionalizado; y iii) una cultura cívica profundamente arraigada en la población. El presidente cuenta con poderes institucionales moderados, los ministros son responsables ante el Parlamento y los gobiernos departamentales cuentan con ciertos grados de autonomía. El Parlamento es una institución central en los procesos de gobierno ya que la aprobación de leyes es la única forma de modificar la orientación de las políticas públicas. Los partidos políticos presentan organizaciones extendidas en todo el país, con fracciones internas bien organizadas y liderazgos políticos de prestigio. La sociedad civil cuenta con importantes niveles de integración y sus organizaciones (sindicatos, gremios, cámaras, asociaciones) cumplen adecuadamente con las funciones típicas de la intermediación[1].

El Estado uruguayo ejerce el monopolio de la fuerza en todo el territorio del país, desempeña funciones importantes en la economía (teléfonos, energía, aguas, servicios bancarios, seguros, etc.) y desarrolla políticas sociales en múltiples áreas (salud, educación, pensiones, seguros de desempleo, etc.). El Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud (SNIS) es un estructura poderosa, integrada por la Administración de Servicios de Salud del Estado (hospitales públicos), las Instituciones de Asistencia Médica Colectiva (mutualistas y hospitales privados), el Fondo Nacional de Salud (FONASA) y la Junta Nacional Administradora del Sistema de Salud. Los empleadores y trabajadores pagan una alícuota al FONASA y los prestadores públicos y privados reciben una monto o cápita por cada persona que atienden[2]. El SNIS atiende al 90% de la población e insume una inversión de casi 6 puntos porcentuales del PBI (22% del presupuesto nacional). El resto de los ciudadanos cuentan con atención médica específica (militares y policía) o con seguros privados integrales diseñados para sectores de ingresos altos[3].

Otra institución relevante de las políticas sociales es el Banco de Previsión Social, encargado del pago de las jubilaciones y pensiones y de otras prestaciones relevantes como el seguro de desempleo o las asignaciones familiares[4]. Finalmente, debe mencionarse al Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, encargado de un conjunto de programas focalizados en la población más vulnerable. Al momento de la llegada de la pandemia, con un detallado mapeo de los sectores informales de la ciudadanía y con capacidad de brindar una atención básica de supervivencia[5].

El Estado uruguayo también cuenta con importantes capacidades en materia tecnológica. La empresa estatal ANTEL conecta a internet al 85% de las familias, de los cuales tres cuartas partes cuenta con fibra óptica en sus hogares[6]. Asimismo, el Plan de Conectividad Educativa de Informática Básica para el Aprendizaje en Línea (Plan Ceibal)[7], desarrollado desde 2005 a partir de la iniciativa One Laptop per Child, funciona como una plataforma educativa que provee un conjunto de programa y recursos educativos para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje. Los avances en conectividad también permitieron un fuerte desarrollo de medios de pago electrónicos a partir de la inclusión financiera de la población formal[8].

Finalmente, Uruguay contaba a comienzos de 2020 con una sociedad integrada, con bajos niveles de pobreza (9% de los hogares) e importantes niveles de igualdad (los más altos en América Latina)..

Estas estructuras políticas y sociales, desarrolladas y potenciadas durante los últimos quince años, permitieron al nuevo gobierno adoptar decisiones críticas sin generar situaciones de tensión o protesta social. El confinamiento podía funcionar mejor cuando la mayor parte de la población tiene resuelto el ingreso monetario, la cobertura en salud es adecuada, funciona perfectamente la conectividad a internet y los cursos educativos a distancia pueden ser impartidos sin mayores inconvenientes.

La estrategia de Lacalle Pou, la actitud de la oposición y la respuesta ciudadana

El 1º de marzo de 2020, el nuevo presidente tomó posesión del cargo, designando un gabinete de coalición que le garantizaba una mayoría legislativa en ambas cámaras. El programa del nuevo gobierno estaba orientado a reactivar la economía, corregir algunos indicadores macroeconómicos y enfrentar decididamente la creciente inseguridad que vive el país. El gobierno había diseñado un proyecto de ley de tipo ómnibus -con más de 500 artículos que modificaban unas 30 políticas públicas-, que sería enviado al Parlamento a finales de marzo, bajo el procedimiento constitucional de la urgente consideración (con un plazo de 90 días).

Sin embargo, el normal desarrollo de los acontecimientos se vio alterado el viernes 13 de marzo por la aparición de los cuatro primeros casos de Covid19. Esa misma noche, el presidente Lacalle Pou realizó una conferencia de prensa con el objetivo de declarar el estado de emergencia sanitaria nacional a causa de la pandemia. Las medidas implementadas por el gobierno esa misma noche fueron contundentes. Se suspendieron todos los espectáculos públicos, se cerraron los centros turísticos, se solicitó a las autoridades departamentales la cancelación de todas las actividades que generaran aglomeraciones y se estableció el asilamiento por un período de catorce días de las personas afectadas por el virus o que presentaran síntomas asociados. También se suspendieron los vuelos internacionales, se cerraron los aeropuertos y se prohibió el desembarco de cruceros y buques comerciales de zonas de alto riesgo; y se prohibió el ingreso al país de toda persona proveniente de la República Argentina (Decretos 93/2020, 94/2020 y 100/2020)[9]. Un decreto del lunes 16 de marzo (101/2020) suspendió por quince días los cursos regulares en todos los niveles de enseñanza pública y privada. Vencido ese plazo, el gobierno suspendió las clases por tiempo indeterminado. Otro decreto del 23 de marzo (103/2020) prohibió el ingreso de ciudadanos brasileños y estableció procedimientos para la gestión de la pandemia en las ciudades binacionales de frontera. Finalmente, un decreto del 25 de marzo (109/2020) permitió a los trabajadores mayores de 65 años permanecer en sus hogares hasta el 31 de julio, percibiendo su salario si podían realizar teletrabajo o en caso contrario, un seguro de desempelo.

A fines de marzo, el Poder Ejecutivo envió al Parlamento un proyecto de ley que creaba el Fondo COVID-19 destinado a solventar las políticas de protección social, las erogaciones extras del Sistema Integrado de Salud, las actividades del Sistema Nacional de Emergencias y las prestaciones extras por seguro de desempleo. El Fondo se formó con las utilidades del 2019 del Banco República y de la Corporación Nacional para el Desarrollo; con las donaciones de dinero que pudieran realizar personas o empresas, y con los préstamos de organismos internacionales y multilaterales de crédito que el país tomaría. El proyecto también creaba el “Impuesto Emergencia Sanitaria COVID-19″, que gravaba con tasas de entre un 5% y un 20% a los salarios de los altos servidores del Estado, gobiernos departamentales, entes autónomos y servicios descentralizados. El impuesto fue aplicado durante dos meses y alcanzó a toda la clase política (presidente, ministros, parlamentarios y autoridades departamentales) y a las máximas autoridades de la burocracia pública (gerencias del Estado). Un segundo proyecto de ley enviado al Parlamento reconocía al COVID-19 como una enfermedad profesional de los trabajadores de la salud. Un tercero, establecía normas y procedimientos para la regulación e instrumentación de la telemedicina en todos los prestadores de salud. El Parlamento aprobó los tres proyectos por unanimidad en un plazo de ocho días en promedio.

Durante los primeros quince días de la pandemia, el gobierno realizó diez conferencias de prensa en el horario central de televisión con el fin de informar sobre la situación sanitaria y explicar las medidas que se iban adoptando. La comunicación del gobierno estuvo centrada en la figura del presidente quien una y otra vez exhortó a la población a “quedarse en casa” voluntariamente. Para el presidente, esa sería la forma en que los uruguayos ejercerían responsablemente su libertad individual en una situación crítica.

Otro acierto del gobierno consistió en crear a mediados del mes de abril el Grupo Asesor Científico Honorario (GACH), liderado por tres científicos de gran reputación en el país e integrado por más de un centenar de expertos en diversas disciplinas. Las pocas conferencias de prensa brindadas por los líderes del GACH generaron seguridad en la ciudadanía y un respaldo unánime a la estrategia del gobierno.

Si bien en los hechos, las políticas del gobierno suponían un cierre de la sociedad, algunos actores relevantes cuestionaron la estrategia. El menú de opciones que ofrecía el mundo en la primera quincena de marzo suponía imponer un lock-down como lo hacían España, Italia o Francia, o apostar al contagio de rebaño como lo hacían Suecia, Reino Unido o Estados Unidos. El Sindicato Médico del Uruguay, el ex presidente Tabaré Vázquez (reconocido oncólogo), la central sindical y algunos miembros del gabinete -entre ellos, el ministro de Salud Pública-, reclamaron al gobierno el establecimiento de una cuarentena total. Sin embargo, Lacalle Pou no cedió a las presiones. Creía que cuánto más intenso fuera el cierre, más difícil sería la recuperación de la normalidad y de la economía del país.

Pese a las diferencias iniciales, todo el sistema político se alineó con la estrategia del gobierno. La exhortación a quedarse en casa fue publicitada por casi todos los actores relevantes del sistema. El Parlamento nunca dejó de sesionar y durante los treinta días posteriores a la aparición de la pandemia se sancionaron nueve leyes relativas a la crisis en un tiempo record y con votos de todos los partidos. Además, los ministros involucrados directamente en la emergencia sanitaria no fueron convocados al Parlamento hasta entrado el mes junio. El número de pedidos de informes cursados por los parlamentarios en el primer mes de pandemia fue realmente bajo (23) en contraste con lo que ocurría en otros países (en Chile, por ejemplo, se cursaron en los primeros 30 días de la pandemia un total de 423 preguntas). Por tanto, el respaldo de la oposición permitió al gobierno trabajar con tranquilidad en el diseño e implementación de una política sanitaria centrada en la creación de protocolos, procedimientos de testeo y rastreo de casos.

El comportamiento de la ciudadanía es una de las piezas clave para comprender el exitoso puzle uruguayo. A comienzos de abril, los ciudadanos estaban informados, respetaban la pandemia, apoyaban al gobierno y consideraban responsable la conducta de la oposición. El Monitor de Grupo Radar muestra que a comienzos de abril, un 95% de los montevideanos se informaban al menos una vez al día sobre la marcha de la pandemia; un 90% tenía temor al contagio y un 85% estaba dispuesto a usar tapabocas en lugares públicos. Un 66% consideraban convenientes las medidas del gobierno y un 56% juzgaba como responsables la conducta de la oposición. A finales de julio, los informados se ubican en el 84%; los temerosos al contagio en un 77%; los dispuestos a usar tapaboca en el 88%; los que apoyaban las medidas del gobierno en un 67% y los que juzgan como responsable a la oposición, en un 52%[10]. Sin la actitud activa de la ciudadanía respecto a los riesgos del coronavirus y sin el apoyo explícito a la conducción del gobierno y al desempeño de la oposición, difícilmente Uruguay hubiese alcanzado resultados positivos en un período de tiempo tan breve.

La evolución de la pandemia y el lento regreso a la normalidad

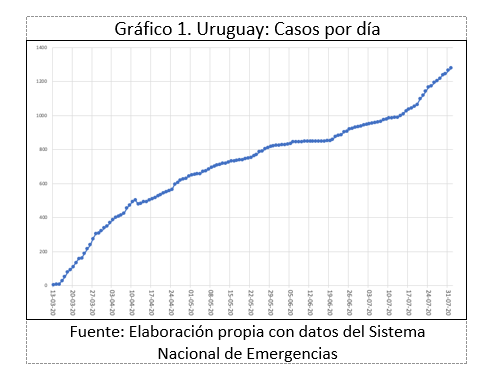

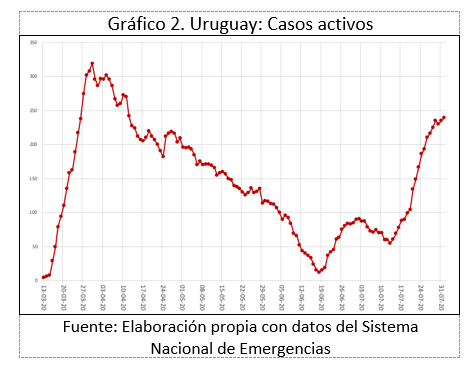

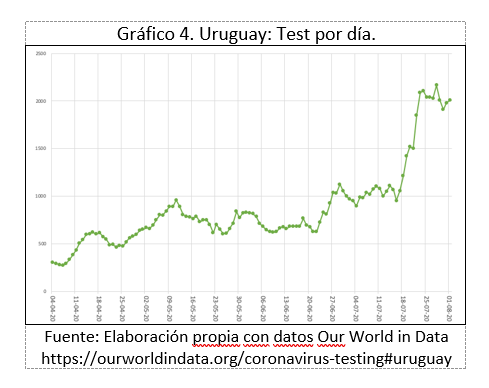

Durante el primer mes de pandemia el aumento de casos tuvo un comportamiento lineal (ver gráfico 1). El brote inicial fue controlado mediante un rastreo exhaustivo de los contactos de las personas contagiadas. El número de test todavía era bajo (inferior a 500 diarios) pero la circulación de los ciudadanos era mínima. Según Google Uruguay[11], la asistencia a actividades recreativas se redujo en un 75% en la segunda quincena de marzo; las visitas a lugares públicos, un 79%; el uso del transporte público, un 71%; y la circulación en supermercados y tiendas de alimentos, un 45%.

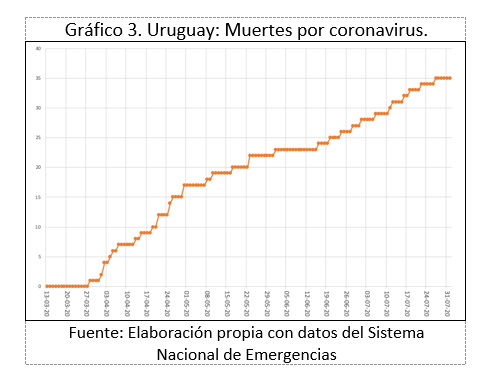

A partir del mes de abril comenzaron a apreciarse los primeros resultados del confinamiento voluntario. El indicador más relevante para apreciar esto es el número de personas que cursaban la enfermedad. Entre el 4 de abril y el 18 de junio, la cifra de contagiados cayó de 302 a sólo 12 (ver gráfico 2). El número de personas fallecidas a fines de mayo apenas superaban las dos decenas y el número de test continuaba en aumento (ver gráfico 3).

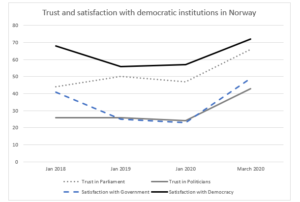

Los resultados auspiciosos impulsaron al gobierno a iniciar el proceso de reapertura bajo estrictos protocolos de seguridad. El primer paso se dio el 22 de abril con el retorno de las clases presenciales en las escuelas rurales del interior del país. En las ciudades, el retorno de las escuelas y centros de educación secundaria se produjo en etapas durante el mes de junio. En la primera quincena de ese mes también reabrieron los grandes centros comerciales, bares, restaurantes e iglesias. Durante el mes de julio, el gobierno continuó aprobando protocolos de reapertura en diferentes áreas de la actividad económica y social. A comienzos de agosto, regresaron los teatros, museos y espectáculos deportivos.