Sophia Moestrup

At the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, there was widespread concern that Sub-Saharan Africa’s weak health care systems would not withstand the onslaught of sickened patients. Observers also worried that fragile democratic systems would be no match for authoritarian temptations and that emergency measures would enable executive excesses and overstay in office.

So what has the impact of the pandemic been to date, on Africa, in terms of health outcomes, emergency power excesses and elections? As discussed in the following, the coronavirus has so far affected the continent less than other parts of the globe, and divergent trends have emerged in terms of the impact of emergency measures on political processes and elections.

Health outcomes

About 17% of the global population lives in Africa, but as of early July the continent had registered only 4% of total cases of COVID-19 in the world, and only 2% of global deaths from the disease [see daily updated statistics from Worldometers]. While these figures could reflect underreporting due to limited testing capabilities, they are also likely the result of fewer imported cases and earlier government action. Most African countries moved swiftly to introduce travel bans, restrictive measures on internal movement and bans on large social gatherings. Africa also has a younger population and prior experience fighting infectious diseases such as Ebola.

The WHO has, however, recently expressed concerns that the disease is spreading beyond capital cities, and there has been a rapid increase in case numbers across the continent since late May. South Africa has been by far the most affected country in Sub-saharan Africa (with over 215,000 cases as of July 7), followed by Nigeria (30,000) and Ghana (22,000) in West Africa, and Cameroon (15,000) in the Central Africa region.

Use and abuse of emergency powers

Crisis responses across the continent have mirrored measures adopted by Europe, the US and other countries: states of emergency, lockdowns and curfews, border closures and limitations on internal travel, bans on gatherings and suspension of public events, in addition to business and school closures.

The widespread adoption of emergency measures has raised concerns about the erosion of democratic fundamentals such as freedom of speech and assembly. Recent research published by the V-Dem Institute based on data preceding the pandemic has found that “democracies are 75 percent more likely to erode under a state of emergency than without.” The paper calls on observers to “scrutinize the intent of the leader” declaring the emergency as it may represent an “opportunity structure” for a budding autocrat already intent on dismantling democratic institutions (p.20). So in other words, it is how emergency declarations are used that matters. That is true in Africa as well as in Europe and elsewhere.

So what are some emerging trends in Africa in terms of use and abuse of emergency provisions?

Leaders in some autocracies — countries classified as “not free” by Freedom House (FH) — like Uganda and Zimbabwe, have indeed abused COVID-19 emergency powers and sought to limit accountability for their management of the crisis. For example, authorities in Uganda have targeted LGBT persons, arrested for violating physical distancing regulations, and retained opposition MPs and others demonstrating against the government’s approach to handling the virus. In Zimbabwe, three female opposition activists arrested for leading a protest against draconian lockdown measures disappeared while in police custody and were allegedly tortured and sexually abused. Governments in Uganda and Zimbabwe have also used control over food aid as a tool to consolidate power. Press freedoms have not fared well either. Several reporters have been detained in Zimbabwe while covering the pandemic, and in Equatorial Guinea, a TV-program and seven journalists were suspended after a debate on corona crisis management in the country. Government attempts at limiting access to information on the spread of COVID-19 have also affected the WHO in Equatorial Guinea as well as Burundi, where the UN organization’s representatives have been expelled.

In countries where greater freedoms exist — classified as “free” and “partly free” by FH — there have been instances of successful pushback against governments’ attempts to expand or maintain emergency measures. In Liberia, the legislature has played an active role in regulating executive emergency powers. In Malawi, the High Court halted the government’s lockdown order following a petition by civil society groups arguing that citizens’ needs had not been provided for, while in South Africa a court ruled against some lockdown regulations found to be “irrational.” In Nigeria, civil society successfully advocated for the House of Representatives to hold a public hearing on the adoption of a controversial new Infectious Diseases Control Bill. Criticized for his government’s handling of the crisis, including violent crack-down on youth demonstrating against COVID-19 restrictions, President Macky Sall of Senegal lifted the state of national health emergency on June 30. In other words, in countries where legislatures and courts are functioning independently and civil society actors have room to organize, they can effectively constrain executive emergency powers, including under the present pandemic.

While these are some general trends, the impact of the pandemic on political processes has to be analyzed and understood as it plays into the political and institutional context of individual countries. In Guinea (classified as “partly free” by FH) that has seen repeated protests against efforts at removing presidential term limits, President Condé imposed a state of emergency four days after a controversial constitutional referendum in March. With a lockdown and ban on gatherings of more than 20 people in place, the government proceeded to release referendum results that pave the way for Condé standing for two more terms with the adoption of a new constitution. Meanwhile, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (classified as “not free” by FH) paradoxically has a higher “democratic quality” score for its executive response to the crisis than Ghana (classified as “free” by FH), according to the Pandemic Democracy Tracker of the Westminster Foundation for Democracy.[1] In the DRC, pandemic politics is shaped by the country’s semi-presidential system where president and prime minister share executive power. Currently, the DRC has a divided executive, with recurring tensions between President Tshisekedi and the coalition led by former President Kabila that controls the legislative majority and the prime minister’s office. Tshisekedi’s emergency measures were contested by the legislature and are time bound. Also, ironically, tensions between the president and legislative majority have left space (at least temporarily) for the judiciary sector to carve out greater autonomy and a gain “in vitality during the state of emergency.” In contrast, in Ghana new sweeping emergency legislation to restrict people’s movements during the COVID-19 crisis has reduced government accountability. The legislation passed by a solid legislative majority backing President Akufo-Addo does not have an expiry date. Opposition leaders and scholars agree the government should instead have relied on constitutional emergency powers renewable by the legislature every three months. This is a particularly fraught issue as the country prepares for presidential elections in December.

Elections

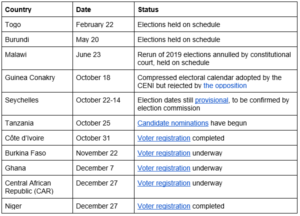

Ghana is just one of 11 countries in Africa holding presidential elections this year, see table below. What impact has the coronavirus pandemic had on these elections so far? Have election calendars or COVID-19 related restrictions been manipulated for the benefit of incumbents or the ruling party? Have appropriate protective measures been adopted in those countries where elections have been held?

Table 1. Presidential elections in Africa in 2020

As the table shows, three presidential elections already took place on schedule, and Guinea held its highly controversial constitutional referendum on March 22. In Togo, elections were held before the first coronavirus case was confirmed in early March. In Burundi, then-President Nkurunziza effectively hindered a planned international observation mission by announcing observers would have to quarantine for 14 days. The announcement came less than two weeks before election day, and despite Nkurunziza otherwise downplaying the threat of the virus and ascribing the low number of recorded cases in Burundi to “divine grace.” Not surprisingly the ruling party candidate, Evariste Ndayishimiye, won. In contrast, in Malawi, while President Mutharika tried to leverage emergency powers to clamp down on opposition ahead of last month’s presidential election, he still lost his bid for re-election. Mutharika was ultimately unsuccessful in the face of a united opposition, strong independent institutions such as the judiciary, the election commission and the army, and a determined civil society.

In Malawi, Guinea and Burundi measures to protect voters, election officials and campaigning candidates from the coronavirus were minimal or inconsistent at best. The pandemic likely contributed to lowering voter turnout in Malawi to 65% from 74% in 2019. In Guinea, the president of the election commission died of COVID-19 shortly after the referendum. In Burundi, there have been unconfirmed reports that Nkurunziza’s sudden death less than three weeks after the election was similarly due to the coronavirus. These high profile deaths underscore the risks of organizing elections without sufficient protective measures against the virus.

Preparations for the remaining presidential elections are proceeding and scheduled dates are so far maintained, despite delays in voter registration in several countries.

Election delays would be highly controversial in Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire and Niger, where incumbent presidents are coming to the end of their terms under the constitutions under which they were elected. Supporters of President Condé of Guinea argue he can stand for reelection under the new constitution approved in March. If the government’s approach to the referendum is any guide, the presidential poll will proceed according to or close to the current compressed electoral calendar without meaningful dialogue with the opposition over ways to ensure a credible race. In March, a last-ditch attempt at facilitating dialogue by a mission of regional heads of state was cancelled under the pretext of the pandemic. In Côte d’Ivoire, there had been speculation that President Ouattara could delay the election as COVID-19 cases spread. Now with the sudden passing of Prime Minister and ruling party candidate Amadou Gon Coulibaly on July 8 after two months of medical leave in France, those speculations may well become reality. In Niger, where President Issoufou has repeatedly voiced his intention to transfer power to an elected successor in the country’s first peaceful hand-over of presidential power, there is significant pressure on the election commission to keep the presidential election date.

In countries where incumbent presidents are not term limited, decisions around the electoral calendar in a COVID-19 context are still potentially controversial. In Tanzania, President Magufuli has declared the country coronavirus free and is pressing ahead with election preparations. His approach to the pandemic has resembled Nkurunziza’s (countering COVID-19 with prayers), and he is similarly suspected of preparing for an election without international observers. President Akufo-Addo of Ghana has had a more reasoned approach to maintaining the electoral calendar as is, referring to the absence of constitutional provisions allowing for an extension of his term. Faced with similar constitutional constraints, the ruling party in the Central African Republic initiated amendments to allow an extension of presidential and legislative terms in case of “force majeure.” The Constitutional court rejected the amendments, however, referring to constitutional articles that “lock in” provisions for the number and length of presidential terms. The court has instead recommended a national consultation to find a consensual solution, should postponing the elections become necessary.

In Burkina Faso, President Kaboré has proactively adopted a consultative approach, engaging opposition leaders in discussing whether, and if so how, to maintain the election date. The election commission of the Seychelles follows a similarly consultative approach. Unrest in Ethiopia following parliament’s unilateral decision to indefinitely postpone elections under the country’s parliamentary system and extend Prime Minister Abiy’s term, is a cautionary tale of the risks of insufficient consultations around such decisions.

Conclusion

Emergency measures associated with the coronavirus pandemic have provided an “opportunity structure” for leaders with authoritarian tendencies in Africa and elsewhere. Autocratic regimes have added these measures to their toolbox of repression and control, including in Burundi to limit independent oversight of the presidential election. Opportunistic delays of elections have not occurred as yet. However, “partly free” countries that have seen shrinking political space in recent years, such as Guinea and Tanzania, are at risk of further authoritarian excesses as elections approach. In these countries, the pandemic can provide cover for limiting freedoms of expression and assembly while hindering the presence of external observation missions. In contrast, in countries with stronger independent institutions and an active civil society, such as South Africa, Senegal and Nigeria, countervailing controls have limited the political risks of the current emergency situation. Similarly we see that reform-minded leadership in countries such as Niger and Burkina Faso matters. In Chris Fomunyoh’s words, we are observing two opposing currents of “democratic resilience” versus “authoritarian opportunism.” However, the impact of the pandemic on political processes and elections is context-specific and must be analyzed as such.

The coronavirus is unfortunately still spreading across the continent, and democracies do not appear better at taming it thus far: we have seen South Africa and Ghana among the countries with the highest numbers of registered cases – though that could be linked to more testing and tracing, in contrast to the suppression of data in countries like Burundi and Tanzania. At any event, more consultative approaches to making tough decisions, notably around elections in a COVID-19 context, are likely to increase transparency, build trust and contribute to further strengthening the resilience of nascent democratic institutions and processes. In contrast, manipulation of emergency measures and repression of information on the spread of the virus may well weaken rather than strengthen the position of autocratic leaders in countries with an increasing COVID-19 caseload.

[1] The tracker monitors the quality of democratic responses to COVID-19 across more than 30 countries, including how expansive executive responses are in terms of restrictions on civil liberties and whether they have sunset clauses.