Thiago Nascimento da Silva

Coalition formation is as common in presidential systems as in parliamentary systems (Deheza, 1998; Cheibub, 2007; Camerlo and Martínez-Gallardo, 2018; Chaisty, Cheeseman, and Power, 2018), and studies comparing parliamentary and presidential systems have suggested that the incentives for coalition formation are similar in both systems of government (Cheibub and Limongi, 2002; Cheibub, Przeworski, and Saiegh, 2004; Cheibub, Elkins, and Ginsburg, 2014). However, we still do not understand the similarities and dissimilarities of coalition dynamics (i.e., coalition formation, monitoring, and termination) between systems of government. This is the main contribution of my dissertation, which I recently defended at Texas A&M University: A comparative perspective study to understand when and why we should expect similarities and differences in coalition dynamics between presidential and parliamentary democracies, and within presidential systems.

In each of the empirical chapters, I develop theories to understand how coalitions are formed (Chapter 1), how coalition members monitor one another (Chapter 2), and why coalitions die in presidential systems (Chapter 3). In this post I briefly discuss each of the studies conducted in these chapters, and suggest future research.

CHAPTER 1. The Formation of Coalitions and the Distribution of Power within Executive Cabinets

Comparative politics scholars view the executive as dependent upon the legislature in parliamentary systems, but independent from the legislature in presidential systems. I argue for a more nuanced comparison between these systems of government. While it is true that confidence procedures make prime ministers more dependent upon the legislature than presidents, the need for executives in both systems of government to make policies means that all presidents are dependent upon the legislature to some degree. I theorize that the degree of presidential dependence on the legislature depends on institutional provisions that allow some presidents greater leeway in making policies. I then demonstrate that the variation in the dependence of the president on the legislature to make and enact policies has implications on how governments are formed in presidential democracies.

1.1. Executive-Legislative Interdependence and Coalition Formation

In all systems of government, the chief executive wants to: 1. survive, and; 2. legislate. Coalition formation by the formateur in parliamentary systems has a direct effect on survival, through the no-confidence procedure (no-confidence constraint), and a direct effect on policy through governing parties’ commitment to vote for the agenda of the government (legislative constraint). Therefore, dependence is introduced in two ways in parliamentary systems. In presidential systems, however, coalition formation can affect policy but not the survival of the government, or at least not directly. Other than in exceptional cases, presidents will remain in power even under adverse legislative conditions. Thus, in presidential systems, dependence is present in one way only: the president depends on the legislature to legislate (e.g., needing legislative majorities to approve her policy agenda).

Recent studies (Amorim Neto and Samuels, 2010; Indridason, 2015; Ariotti and Golder, 2018) provide evidence that this institutional difference (i.e., the absence of a no-confidence procedure in presidential systems) is crucial for understanding why we do not see the same pattern in the allocation of portfolios between parliamentary and presidential democracies. The expectation from these studies is that the president’s party should receive a higher allocation of portfolios as compared to the share of legislative seats it contributes to the coalition (i.e., a formateur’s advantage.) However, as I argue in this study, distinctions within presidential systems must be used to explain the substantial variation we see in the allocation of portfolios to presidential parties.

Presidents can have a greater or lesser influence on policy, depending on how dependent they are on the legislature to make and enact policies. This dependence relies on presidents’ policy-making powers granted by constitutions. These powers affect the bargaining strategy between the president and the legislature, which, consequently, affects the composition of cabinets. According to my theory, a greater share of portfolios controlled by presidential parties should be observed in countries where, ceteris paribus, presidents have a greater opportunity to influence the policy agenda in the legislature. An empirical implication to be tested in this study, then, is that the greater the president’s policy-making powers, the greater the president’s party portfolio share. In turn, the lesser the policy-making powers of the presidents, the more dependent they are on the legislature to legislate, and then we should see a more proportional distribution of portfolios (as we commonly see in parliamentary systems), i.e., a distribution of power within the executive cabinet that resembles the distribution of power within the legislature.

1.2. Results and Discussion

The unit of analysis in this study is the governing party within the coalition, considered yearly. A government coalition is composed of the formateur’s political party (which is always the presidential party in presidential systems) and all parties that accept the ministerial posts offered by the formateur. Hence, a governing party is defined according to whether a party holds a cabinet membership—that is, if the party controls at least one portfolio.

The empirical analyses were conducted using the most comprehensive data collected to date from 13 Latin American presidential multiparty democracies. The data comprise a total of 52 presidential administrations and 36 presidential parties spanning 58 years (1959–2017), consisting of 187 observations in total.

The dependent variable (DV) is the President’s Portfolio Balance (PPB). This variable is the difference between formateur’s portfolio share and formateur’s governing seat share, and it measures the balance of the portfolio share controlled by the presidential party. PPB could range between -1 to +1. A positive value indicates that the president’s party is receiving more portfolios relative to the share of legislative seats it contributes to the coalition. A value of 0 indicates that the president’s party receives the same proportion of portfolios as the share of legislative seats it contributes to the coalition. A negative value in PPB means that the president’s party is receiving fewer portfolios than expected if perfect proportionality between portfolio share and seat share contribution holds.

The main independent variable is the President’s Policy-Making Powers. Developed by Montero (2009), the legislative institutional power index (IPIL) measures the institutional potential of the presidency to influence the legislative activity vis-à-vis the legislature. The measure ranges from 0 to 1, in which values close to 1 indicate a greater influence of the president on the legislative activities. Values close to 0 indicate a smaller influence of the president on the legislative activities.

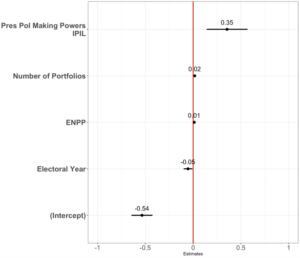

Figure 1 depicts the OLS results for the main empirical implication tested in this chapter. Controlling for electoral year, effective number of parties (ENPP), and number of portfolios, the results support the empirical expectation. The estimate for president’s policy-making powers (IPIL) is positive and statistically significant at level 0.05, indicating that the greater the president’s policy-making provisions, the greater the president’s portfolio share.

On average, a one-unit increase in the score for president’s policy-making powers (i.e., presidents with a higher level of policy-making powers), and holding the control variables constant leads to a surplus of almost 4 percent of the share of portfolios controlled by the president’s party, as would be expected considering the share of legislative seats the president’s party contributes to the coalition. At its lowest score, with president’s policy-making powers equal to 0 (i.e., presidents holding the lowest level of policy-making powers), and holding the control variables constant, the president’s party loses, on average, 5 percent of the share of portfolios compared to the share of legislative seats it contributes to the coalition (constant estimate equal to -0.54 and significant at level 0.05).

Figure 1. President’s Portfolio Balance (PPB) Within Presidential Democracies

(DV = PPB)

In substantive terms, El Salvadorian president Mauricio Funes (2009-2013) held the lowest score for president’s policy-making powers in the dataset at 0.26, and his party, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMN), contributed 75 percent of the legislative seats to the coalition, while controlling only 54 (2009), 41 (2010), and 33 (2011) percent of the portfolios available in the cabinet. In 2012 and 2013, the FMNL contributed 94 percent of the legislative seats to the coalition, but held only 25 and 17 percent, respectively, of the portfolios available. Chilean president Eduardo Frei (1998 and 1999) held the highest score for president’s policy-making powers in the dataset at 0.71, and his party, the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), contributed 58 percent of the legislative seats to the coalition and controlled 66 percent of the portfolios available in the cabinet, a case of formateur’s advantage.

The score for Colombian president Ernesto Samper’s policy-making powers in 1995 is the median value for the main independent variable, equal to 0.52. In that year, Samper formed a cabinet in which his party (Liberal Party) controlled 71 percent of the cabinet portfolios available while contributing 69 percent of the legislative seats of the coalition, a case of proportional distribution of portfolios.

As revealed by these results, the likelihood of a more proportional distribution of portfolios or a deficit in the share of portfolios controlled by the president’s party increases as the president’s ability to shape the legislative agenda decreases. If the president is more dependent upon the legislature to make and enact policies, then the balance of power in presidential cabinets is more likely to reflect the balance of power in the legislature. In this case, the presidential cabinet can be very similar to the proportional cabinets usually formed in parliamentary systems. However, when institutional provisions allow some presidents greater leeway in making and enacting policies, then a more disproportional distribution of portfolios to the benefit of the president’s party is expected.

CHAPTER 2. Why and When do Presidential Cabinet Members Monitor One Another?

A recent literature on parliamentary systems shows that coalition members keep tabs on their partners to prevent ministerial policy drift (Thies, 2001; Martin and Vanberg 2004). Building on this literature, in the second chapter of my dissertation I explore intra-coalition politics in a presidential democracy. By analyzing more than 20,000 information requests made between 1995 and 2014 by members of the Brazilian Congress to individual ministers, in this chapter I am able to demonstrate that, in fact, policy monitoring occurs in all levels of the coalition, including monitoring between non-presidential members. As I theorize in this chapter, presidential coalition partners participate in more policy monitoring when the policy divergence (ideological distance) between them is greater. Thus, similar to parliamentary systems, coalition partners in presidential democracies have an incentive to, and do, keep tabs on one another.

2.1 Policy Monitoring in a Presidential Democracy: Evidence from Brazil

Coalition governance inevitably boils down to an ongoing contest between partners to maximize their political power, with coalition partners adopting monitoring and control mechanisms to reduce their agency loss and solving conflicts arising from delegation. While the literature on parliamentary systems identifies monitoring activities between coalition partners within the executive and legislative branches (Thies, 2001; Martin and Vanberg, 2004; Lewis, 2009; Carroll and Cox, 2012), the literature on presidential systems has thus far been restricted to both the arena in which the monitoring takes place—i.e., the executive arena—and to the actor that initiates the monitoring, i.e., the president (Inácio and Rezende, 2015; Gaylord and Renno, 2015; Freitas, 2016; Pereira, Batista, Praça, and Lopez, 2017).

Building on the principal-agent theory, my argument is that coalition partners in presidential systems monitor the policies implemented by one another to reduce the information deficit coming from heterogeneous cabinets—i.e., cabinets formed by ideologically-distant parties. The empirical implication is that as the ideological distance between cabinet parties increases, greater policy monitoring between coalition partners is expected.

To conduct the empirical analysis of this study I rely on the use of a legislative prerogative available to Brazilian legislators, called “Request for Access to Information” (RIC). A key tool in the list of accountability resources for the legislative branch, the RIC is a formal and low-cost mechanism for monitoring policies implemented by the executive branch. By requesting access to information through RIC, Brazilian legislators can oversee any act, action or program related to the implementation of public policies from any portfolio of the cabinet. The dataset comprises all RICs initiated by Brazilian legislators between 1991 and 2014, covering 21 multiparty cabinets formed in Brazil, including governments from a range of ideological positions.

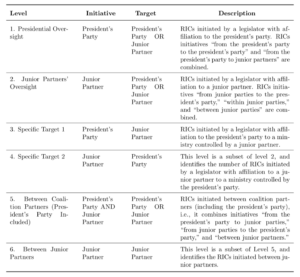

Table 1. All Levels of Policy Monitoring (Within and Between Coalition Partners)

Table 1 describes all possible flows (directions) of policy monitoring between coalition members (junior and presidential partners): 1. Within president’s party (presidential oversight); 2. Within junior partners (junior partner’s oversight); 3. From president’s party to a junior partner; 4. From a junior partner to the president’s party; 5. Between coalition partners (not including the president’s party), and; 6. Between coalition partners (including the president’s party).

To test the effect of the heterogeneity of the cabinet on the number of RICs initiated, the information requirements presented in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies between 1991 and 2014 were grouped in units of time, i.e., number of RICs initiated per quarter. The dependent variable is then a count variable—i.e., number of RICs initiated per quarter—and it ranges from two to 326 RICs initiated.

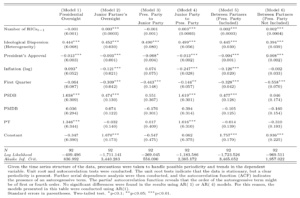

Table 2 depicts the results from Poisson regression models, based on all the directions of policy monitoring. As expected, the results present in Table 2 indicate that policy monitoring occurs at all levels within the coalition. This is suggested by the positive and significant (at level 0.01) estimates for dispersion in all models. This finding highlights that mechanisms to solve intra-coalition conflicts in presidential systems is neither restricted to the executive arena nor pursued only by the president to keep tabs on her partners.

Table 2. Policy Monitoring: Identifying the Author and the Target

(Dependent variable: Number of RICs initiated per quarter)

My expectation of a greater policy monitoring between coalition partners under more ideologically-heterogenous cabinets is also corroborated by the results. The greater the ideological distance between the members of the coalition, the greater the policy monitoring between its members (see the estimates for “Ideological Dispersion (Heterogeneity)” in Table 2. Similar to parliamentary systems, then, presidential coalition governments require a continuous effort by the cabinet members to mitigate the costs of delegating ministry control to parties with different policy preferences.

CHAPTER 3. How Long Will It Last? Presidential Coalition Termination

In the third chapter of my dissertation, I research what circumstances lead to presidential coalition termination. One of the early beliefs about coalitions in presidential systems was that they would form only rarely, and that when they formed, they would be erratic and short-lived. Based on the exclusive powers of the president to form and reshuffle cabinets and the president’s central position within coalition governments, I argue that economic indicators and the public’s evaluation of the president’s performance are crucial factors in predicting coalition termination. By examining 82 cabinets in 10 Latin American democracies, I show that presidential coalitions are more than ephemeral phenomena. They terminate for political and economic reasons, similar to those that can lead to parliamentary coalition termination.

3.1 Institutional Features of Presidential Democracies and their Effect on Coalition Termination

There is no reason to believe that only under presidential systems would being part of the government yield no electoral benefits for junior parties when the economy is performing well and the president is popular with voters. Hence, a study on presidential cabinet termination can take cues from the extensive literature regarding cabinet survival and termination under parliamentary systems. However, some of the theories developed for parliamentary coalition termination are clearly not applicable to presidential contexts. Different from parliamentary democracies, presidential democracies are defined by the mutual independence between the executive and the legislative branches, the fixed electoral calendar, and the absence of certain institutional attributes such as investiture and the vote of no confidence procedure.

In this study, I propose a theoretical framework in which I adapt elements from the extensive literature on cabinet survival in parliamentary systems to the context and specificities of presidential systems. Based on the exclusive powers of the president to form and reshuffle cabinets and the central position of the president within coalition governments, I argue that economic indicators—such as inflation, unemployment, economic growth—and the public’s approval rating of the president’s performance to be crucial factors that predict cabinet termination in presidential democracies.

In order to model the likelihood of coalition termination, I conducted an event-history analysis (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones, 2004). The dependent variable is the durability of the coalitions, as measured by the number of days that the coalition survived. The main independent variables are inflation rate, unemployment rate, GDP growth, and president’s approval rating. The control variables included in the models are: cycle (the elapsing of the president’s term), the size of the coalition, ideological dispersion within the coalition, cabinet coalescence (proportionality of the cabinet), and the effective number of parties (ENP).

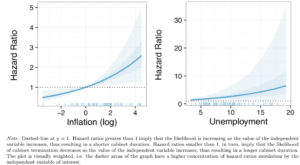

Figure 2 below depicts the estimates for inflation and unemployment, the two main independent variables statistically significant (at 0.01 level).

Figure 2. Hazard Ratios of Cabinet Duration by Inflation (left-side) and Unemployment (right-side)

As we can see in the left-plot of Figure 2, with a positive coefficient estimate for inflation, holding all other variables constant, as the value for inflation increases, the hazard rate increases, thus decreasing the duration of the coalition. Substantively, as inflation increases by one unit, holding the other variables constant, the likelihood of a cabinet termination increases to almost 30 percent []. This result supports the first hypothesis of this study, according to which as the country’s inflation rate increases, a shorter duration of the cabinet is expected.

The second hypothesis—as the country’s unemployment rate increases, a shorter duration of the cabinet is expected—is also supported by the results. The estimate for unemployment while holding all other variables constant is positive and statistically significant (at level 0.05) (see right-plot of Figure 2). Substantively, as the unemployment rate increases by one percent, holding the other variables constant, the likelihood of a cabinet termination increases by close to 10 percent [].

These findings suggest that the termination of coalition in presidential systems follows a logic that fits a rational behavior of the coalition’s members. When the government is successful in controlling inflation and unemployment, cabinet termination becomes less likely. These results are similar to findings regarding parliamentary systems (King, Alt, Burns, and Laver 1990; Warwick 1994; Saalfeld, 2008; Bergman, Ersson, and Hellström, 2015) and reveal that the difference between presidential and parliamentary systems of government with regards to coalition termination is one of degree.

Future Research

This dissertation furthers our understanding of the relationship between the executive and legislature in parliamentary and presidential systems, and opens other avenues for future research on the topic of coalition governments comparing forms of governments. In Chapter 1, I focused on the distribution of portfolios during the government formation process. Other resources (beyond portfolios) distributed by the president in the government formation process can also be explored (e.g., state-owned enterprises, partisan political appointments, and pork-barrel resources). By considering that presidents have other goods to distribute that are of interest to coalition members, we might find that different parties have different “prices,” revealing that presidents don’t buy all coalition members so easily.

As revealed by the literature on parliamentary systems, the ability to police the partners of the coalition consists of monitoring and correcting ministerial drift. In Chapter 2 of my dissertation, I focus only on the first of these tasks, i.e., the policy monitoring initiatives. The correction of the policies in presidential democracies is a topic worthy of further exploration. Coalition partners can potentially use the monitoring process analyzed in this study to scrutinize and amend, for example, bill proposals they believe represent unacceptable drift.

Building on the findings discussed in Chapter 3 on coalition termination, another potential subject for exploration is how recurring ministerial terminations by the president can affect the president’s policy goals and policy-making capacities. Some of the potential questions to be answered on this topic are: Does cabinet duration influence the legislative capacity and success of presidents? Do different cabinet compositions and duration affect the economic retrospective voting?

From a normative point of view, it is worth emphasizing that the choice of the system of government (or its reform) is recurrently considered a solution to problems such as political instability or governance deadlock, especially by political commentators of presidential systems. However, systems of government cannot be taken as complete and closed packages to solve contextual issues such as governance and coalition instability. As I demonstrate in my dissertation, different systems of government may behave more or less similar depending on their internal institutional features.

REFERENCES

Amorim Neto, Octavio, and David Samuels. 2010. “Democratic Regimes and Cabinet Politics: A Global Perspective.” Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos Legislativos 1 (1): 10–23.

Ariotti, Margaret H., and Sona N. Golder. 2018. “Partisan Portfolio Allocation in African Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (3): 341–379.

Bergman, Torbjörn, Svante Ersson, and Johan Hellström. 2015. “Government Formation and Breakdown in Western and Central Eastern Europe.” Comparative European Politics 13 (3): 345–375.

Box-Steffensmeier, Janet, and Bradford Jones. 2004. Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Camerlo, Marcelo and Cecilia Martínez-Gallardo, eds. 2018. Government Formation and Minister Turnover in Presidential Cabinets: Comparative Analysis in the America. New York: Routledge.

Carroll, Royce, and Gary Cox. 2012. “Shadowing Ministers: Monitoring Partners in Coalition Governments.” Comparative Political Studies 45 (2).

Chaisty, Paul, Nic Cheeseman, and Timothy J. Power. 2018. Coalitional Presidentialism in Comparative Perspective: Minority Presidents in Multiparty Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cheibub, José Antonio, Adam Przeworski, and Sebastián Saiegh. 2004. “Government Coalitions and Legislative Success Under Presidentialism and Parliamentarism.” British Journal of Political Science 34: 565–587.

Cheibub, José Antonio, and Fernando Limongi. 2002. “Democratic Institutions and Regime Survival: Parliamentary and Presidential Democracies Reconsidered.” Annual Review of Political Science 5: 151–179.

Cheibub, José Antonio, Zachary Elkins, and Tom Ginsburg. 2014. “Beyond Presidentialism and Parliamentarism.” British Journal of Political Science 44 (3): 284–312.

Cheibub, José Antonio. 2007. Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Deheza, Grace Ivana. 1998. “Gobiernos de Coalición en el Sistema Presidencial: América del Sur.” In El Presidencialismo Renovado: Instituciones y Cambio Político en América Latina, ed. Dieter Nohlen and Mario Fernández B. Caracas: Nueva Sociedad.

Freitas, Andréa. 2016. O Presidencialismo da Coalizão. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Konrad Adenauer.

Gaylord, Sylvia, and Lucio Renno. 2015. “Opening the Black Box: Cabinet Authorship of Legislative Proposals in a Multiparty Presidential System.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 45 (2): 247–269.

Inácio, Magna, and Daniela Rezende. 2015. “Partidos legislativos e governo de coalizão: controle horizontal das políticas públicas.” Opinião Pública 21 (2): 296–335.

Indridason, Indridi. 2015. “Live for Today, Hope for Tomorrow? Rethinking Gamson’s Law.” Working Paper, University of California, Riverside: 1–34.

King, Gary, James Alt, Nancy Burns, and Michael Laver. 1990. “A Unified Model of Cabinet Dissolution in Parliamentary Democracies.” American Economic Review 34 (3): 846–871.

Lewis, D. 2009. “Revisiting the Administrative Presidency: Policy, Patronage, and Agency Competence.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 39 (1).

Martin, Lanny, and George Vanberg. 2004. “Policing the Bargain: Coalition Government and Parliamentary Scrutiny.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (1): 13–27.

Pereira, Carlos, Mariana Batista, Sérgio Praça, and Felix Lopez. 2017. “Watchdogs in Our Midst: How Presidents Monitor Coalitions in Brazil’s Multiparty Presidential Regi.” Latin American Politics and Society 59 (3): 27-47.

Saafeld, Thomas. 2008. “Institutions, Chance, and Choices: The Dynamics of Cabinet Survival.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe, ed. Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thies, Michael. 2001. “Keeping Tabs on Partners: The Logic of Delegation in Coalition. Governments.” American Journal of Political Science 45 (3).

Warwick, Paul. 1994. Government Survival in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.