Valeria Palanza

We often think of Presidential systems vis à vis Parliamentary systems possibly because the latter have been around longer, and as Cheibub (2007) reminds us, separation of powers systems were an institutional innovation that emerged in the Americas during the second half of the eighteenth century. In this comparison, we tend to highlight that presidents are limited in what they can do by the separation of power into three branches that were designed to check each other and ensure that sufficiently representative majorities back decisions –and that minorities are protected.

Checks and balances are a key component of this institutional edifice, and at their best, they provide for a reasonably well-functioning system that promotes moderation and can lead to good government. Presidential systems are at their best when checks and balances are at work, which is not always. The founding fathers failed to imagine a system in which those inhabiting the legislative and judiciary branches of government would not wish to check the executive. Most presidential systems, however, have experienced this situation, and it has led to the concentration of power in executive hands.

In this post I summarize the main arguments and findings in Checking Presidential Power: Executive Decrees and the Legislative Process in New Democracies (2019), which is concerned with the conditions that are linked to a weakened desire to check the executive. The book proposes that legislators and supreme court justices decline to check the president under specific circumstances: when they do not value their decision rights enough to defend them against presidential encroachment. I refer to the valuation of decision rights as institutional commitment, and argue that levels of institutional commitment vary across countries, and within countries across policy areas.

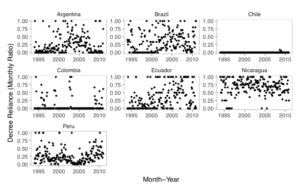

Motivated by the overwhelming resource to lawmaking by executive decree in several Latin American countries, and the interesting variation across countries with very similar institutional structures, the book explores the choice to enact policy by executive decree or congressional statute. The following table illustrates the frequency with which decrees and statutes are enacted in the seven of the ten cases for which data is available. Along with variations within each country across time, there is interesting variation between countries.

Graph 1. Monthly Reliance on Decree in Seven Countries

Checking Presidential Power proposes that where presidents are granted constitutional decree authority (Carey and Shugart 1998), a decision must be made regarding whether to legislate by executive decree or congressional statute. Yet the choice only exists to the extent that politicians value their decision rights sufficiently to stop executive encroachment. An extensive literature on presidential systems has shown that legislators and courts vary in their willingness to confront presidents (Alemán and Tsebelis 2016, Carey and Shugart 1998, Helmke 2005, Helmke and Ríos Figueroa 2011, Jones 1996, Mainwaring and Shugart 1997, Morgenstern and Nacif 2006, Samuels 2002, Spiller and Tommasi 2009, among others). While in some countries politicians are able and willing to confront the executive in the face of encroachment, such is not always the case. The evidence begs a few questions: What determines such willingness? What conditions must be met for policies to change having gone through congress instead of changing merely by executive decree?

More than half of Latin America’s presidential systems provide constitutional decree authority, and providing responses to these questions sheds light on the dynamics behind policy change in those countries. It also allows us to reflect on the consequences of expanding the president’s legislative prerogatives in the United States, as Howell and Moe (2016) propose.

Institutional Commitment

Checking Presidential Power argues that the extent to which legislators will stop the president if she tries to encroach upon their legislative prerogatives, which ultimately affects the choice of legislative path is a function of three factors. First, the allocation of legislative prerogatives across the branches, second, the extent to which politicians value those prerogatives, and third, external actors’ valuation of policy. This is to say that rules play an important role in explaining why legislatures are sometimes bypassed, but rules alone cannot explain levels of reliance on decrees. This caveat introduces the notion of institutional commitment, i.e., politicians’ willingness to defend their decision rights from encroachment. External agents, who are vested in specific policies, place proposals on the table and push for them to prosper.

Importantly, the book highlights that the existence of rules imposing checks on executive behavior is worth nothing if the actors in charge of placing constraints on the executive do not enforce those checks. It outlines the mechanisms leading to politicians’ willingness to check the executive by exercising and enforcing their own decision rights. Those mechanisms are associated to their expectations regarding how long they will remain in their posts and what benefits they derive from their tenure. Decision rights are worth as much as those in possession of those rights are willing to invest to enforce them, and this decision depends on forward-looking calculations: will they continue to be around to use their prerogatives in years to come?

This is to say that legislators who believe they will not remain in congress are also likely to take decision rights associated to their position lightly. If, instead, they value maintaining their posts, and they believe that they are likely to remain in congress for some time, the incentive will be greater to enforce their decision rights. By doing so, they strengthen the institutions they embody, and endow them with added value. These are the conditions under which enforcement is more likely to occur.

Checking Presidential Power confronts a basic empirical puzzle: even weak Latin America congresses pass laws, and oftentimes they pass important ones. Once and again, the ever-powerful presidents portrayed in the literature are left to stand by while bills go through the congressional procedure for approval. If presidents were as powerful as they are often portrayed, and were it so easy to overrun legislators and the supreme court, why do they not simply rule by decree? Why go through the hurdles imposed by the congressional legislative path in countries where decrees are so readily available? While Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Peru have similar institutional arrangements, analysis of the their level of reliance on decrees reveals stark differences. Each of the seven countries is endowed with constitutional decree authority, yet decrees are practically never the legislative instrument of choice in Chile, and they are used in varying levels in the rest of the countries.

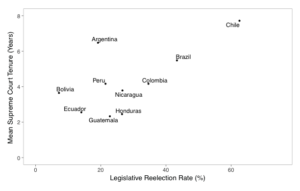

Graph 2 presents how countries fare on two basic indicators of job security across seven Latin American countries. The horizontal axis shows variation along legislative reelection rates, and the vertical axis shows supreme court tenure, indicators of legislators’ and supreme court justices’ expected life in office. Countries are fairly well organized along an imaginary positive correlation line.

Graph 2. Legislative Reelection & Supreme Court Tenure

Regarding variations in levels of reliance on decrees within countries, the puzzle is slightly different. We know some countries rely more heavily on decrees than do others. But within a given country, what explains the choice to enact a specific policy by decree, and yet another one through a congressional statute? Again, the answer depends on levels of institutional commitment.

On one end of the continuum, where institutional commitment is at its highest, we expect decrees to be enacted under truly extraordinary circumstances, very sparingly. At the opposite end of the continuum one might find decrees taking over. Most countries, however, have levels of institutional commitment such that decrees are chosen often yet not always. In these cases, whatever level of institutional commitment politicians of one branch have in a given country interacts with their valuation of what is at stake in that case, surrounding that specific policy on a specific issue. The claim is that different policy issues vary in the stakes they raise. The level of resources (votes, organizational capacities, ability for mobilization, economic resources, among others) that an issue commands affects the stakes around that issue. So in one country it may be the case that labor policy or energy policy is high stakes, while agricultural policy or health policy is low stakes, and this may be different in a neighboring country. Whether the stakes are high or low tells us whether the issue attracts attention from resourceful agents on more than a single side of the debate surrounding it. If it does, the stakes increase; if it does not, they tend to be low.

So far, I have suggested (a) that levels of institutional commitment are fixed within specific countries, and (b) that commitment to the enforcement of prerogatives is activated to different extents by different policy areas. Yet when conducting country-specific analyses, the level of institutional commitment is fixed, while allowing for variation in the extent to which this commitment is triggered. Cross-country analysis requires, instead, analysis of the variation on the institutionally derived dimension. Such variation is captured through an Institutional Commitment Index (created from the two indicators presented in Graph 2, legislative reelection rates and mean supreme court tenure), which is conceived as a proxy of levels of institutional commitment.

Empirical Analysis

Checking Presidential Power presents empirical analyses at two different levels, over the course of three chapters. Two chapters are devoted to within country analyses of Argentina and Brazil, another analyzes the determinants of levels of reliance on decrees across seven countries. In a nutshell, the analysis of the Brazilian and Argentine cases reveal that at higher levels of institutional commitment, as in Brazil, we can expect high-stakes policies to be enacted by statutes, whereas low-stakes policies are more likely to be enacted by decree. When levels of institutional commitment are lower, as in Argentina, the stakes surrounding policies may not be enough of a pull to affect the likelihood of decrees, and more policy seems to be enacted by decree overall. The evidence provided by the case of Chile, where only two decrees were enacted during the entire period under analysis (see Graph 1), suggests that at sufficiently high levels of institutional commitment the stakes surrounding policies may also become irrelevant –fewer decrees are enacted overall. In what follows I will refer to the cross-country analysis.

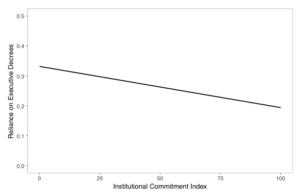

Graph 3.1 shows the effect of the Institutional Commitment Index on levels of reliance on decree. It shows the predicted inverse relation between institutional commitment and reliance on decrees: at higher levels of institutional commitment countries tend to rely less on executive decrees. The book proposes that this is because legislators and supreme court justices in these cases are willing to enforce their decision rights. They value having the prerogative to decide on legislative issues, and they act to defend this right when presidents overstep their turf.

Graph 3.1. Effect of Institutional Commitment on Reliance on Decrees

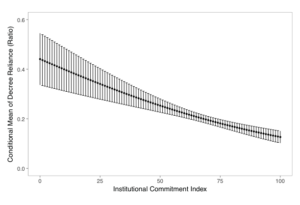

Graph 3.2 shows the effect of the Institutional Commitment Index on the conditional mean of levels of reliance on decrees. It indicates that the effect on reliance on decrees is best predicted at high levels of institutional commitment, as suggested by the smaller margins on the right side of the curve, and predicted with less accuracy at lower levels of institutional commitment. This is in line with what the theory predicts, as below a certain level of institutional commitment it should not make much of a difference –politicians charged with checking the president simply do not care to do so, and decrees may be more likely always. This is precisely what the book explores through the cases of Brazil and Argentina.

Graph 3.2 Conditional Mean of Reliance on Decrees

The underlying conviction of the book is that by understanding the conditions leading to the choice between legislative paths we take steps to understand the mechanisms underlying unilateral action by presidents. Quiescence on the part of the actors charged with checking presidential actions and enforcing checks and balances is the main culprit of concentration of power in presidential hands. By lending insight to the motivations facing actors involved in the process we are able to grasp the microfoundations of the encroachment of decision rights, as well as their enforcement. The checks and balances that stand at the core of separation of powers systems depend crucially on this enforcement.

Far from arguments that highlight presidential self-restraint or cultural traits of respect for institutional provisions, this book places institutional commitment, born of self-interested behavior by legislators and supreme court justices, as the factor standing at the center of the enforcement of checks on the executive. Institutional commitment speaks of politicians’ appreciation for the provisions that make them influential actors in the legislative process, their decision rights. The book proposes that when levels of institutional commitment are higher, politicians are more likely to stand in defense of their decision rights; the evidence coming from the seven countries analyzed confirms this argument: where levels of institutional commitment are higher, presidents tend to rely less on decrees.

Taking Stock

The sample considered in Checking Presidential Power suggests that high levels of institutional commitment are not prevalent in Latin America. Why are high levels of Institutional commitment rare? A legacy of regime instability has placed into this situation, even when the results in this book depend solely on data from current day democracies born out of the latest wave of democratization in the region. The book argues that job stability in top political jobs, fundamentally in the supreme court and the legislature, are fundamental determinants of levels of institutional commitment.

Yet clearly, stability is not easily attained. The strong association between the enforcement of decision rights and job security, the latter linked to longer tenures in the SC and in congress, does suggest that supreme courts that are longer lived and legislators that create careers within congress are more inclined to check presidents with a propensity to overstep their bounds. But we know countries vary in their institutional arrangements, ranging anywhere between banning reelection to legislative jobs and instituting fixed-term short-lived SC benches, to placing no limits on the reelection of legislators and establishing indefinite tenure in the SC. Furthermore, we know that these rules are not alone in determining tenure, other rules not considered in the book may also play a role.

While the book highlights the positive effects of high levels of institutional commitment for democracy, it acknowledges that countries adopt institutions oftentimes in response to problems they confronted in their recent (and not-so-recent) history, and in combination with other institutional traits and political dynamics that are specific to each country. So no evaluation of the effects of specific institutions can be done in isolation of those conditions.

Can countries strengthen institutional commitment? Based on arguments in the book, one might be inclined to believe that by inducing longer tenures in the SC and legislatures, levels of institutional commitment would rise. If so, it might be interesting to understand how, in what way, such a process can be brought about. How can longer tenures be achieved?

Unfortunately, establishing rules that provide for unlimited reelection to congress or indefinite tenure in the SC will not do the trick –at least not alone. They will not necessarily bring rises in levels of institutional commitment, because the connection is not direct. These rules are not the sole determinants of longer tenures, as the abundant literature cited in the book has pointed out. Countries with unlimited reelection to congress and indefinite SC tenure may in practice experience high levels of rotation in both spheres due to other incentives that weigh upon decisions to stay on. Factors from the structure of party lists in systems of proportional representation to intimidation to leave the bench can affect tenure, as research cited in the book shows.

Furthermore, it is not reasonable to expect changes in levels of institutional commitment in short periods of time. Its strengthening, as much as its deterioration, occurs over the long term. Levels of institutional commitment are determined by the current institutional setting and by inter-temporal calculations. On the bright side, this is also why levels will not deteriorate quickly.

Consider the case of the United States of America. Levels of institutional commitment there are certainly at the higher end of the spectrum. Recent events in US politics, such as the executive order signed by President D. Trump on 27 January 2017, a travel ban “Protecting the Nation from foreign terrorist entry into the United States,” provides a glimpse into how the dynamics emphasized by this book come to play. In this specific case, those who claim that partisan support in congress enables the executive to issue decrees certainly have a point. The partisan majority held by republicans in Congress stood still while an expansive ban was placed on travel into the US, countering established policy in this realm. Yet given that this ban violates constitutional rights, the judiciary was able to step in and revert it. To be sure, the judiciary in the US has the capacity to counter the decisions of a standing president because there is a history of judicial independence, and it is difficult to imagine that a standing judge would face losing her job as a consequence of her decisions.

Clearly, this is not always the case outside of the United States. Most interestingly, it may not always be the case in the US: a few weeks into the Trump presidency observers were already wondering whether job security in the judiciary will remain as strong as it has been. But the point is that other countries already face the reality of low levels of institutional commitment, and its strengthening requires a multifaceted approach that can lead to longer tenures.

Politicians are not naïve regarding institutional choices. The powerful actors of today feed off of the current incentive structure, so to expect them to make changes in the direction of strengthening actors that will then limit their discretion simply does not seem reasonable. Such changes require a good dosage of statesmanship, with a dash of altruism. They require a firm conviction by a majority of the actors involved that the strengthening of the branches, which comes hand in hand with the imposition of constraints on the executive, has the power to bring about long-term benefits to the entire polity.

Alemán, Eduardo and George Tsebelis. 2016. Legislative Institutions and Lawmaking in Latin America, Oxford University Press

Carey, John, and Matthew S. Shugart. 1998. Executive Decree Authority. Cambridge University Press

Cheibub, José. 2007. Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy. Cambridge University Press

Howell, William G., and Terry M. Moe. 2016. Relic: How Our Constitution Undermines Effective Government–and Why We Need a More Powerful Presidency, Basic Books

Palanza, Valeria. 2018. Checking Presidential Power. Executive Decrees and the Legislative Process in New Democracies. Cambridge University Press

Mainwaring and Shugart 1997. Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America, Cambridge University Press

Morgenstern, Scott and Benito Nacif. 2002. Legislative Politics in Latin America. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics, CUP

Samuels, David . 2006. Ambition, Federalism, and Legislative Politics in Brazil. Cambridge University Press

Mark P. Jones. 1996. Electoral Laws and the Survival of Presidential Democracies. University of Notre Dame Press

Spiller, Pablo and Mariano Tommasi. 2009. The Institutional Foundations of Public Policy in Argentina: A Transactions Cost Approach. Cambridge University Press