Maryhen Jiménez

Victor Garcia Miranda

The Venezuelan government led by Nicolás Maduro set this year’s presidential election on July 28, the birth anniversary of Hugo Chávez. This symbolic date was intended to galvanize support among Chavista followers and perhaps reignite the passion that once fueled the “Bolivarian Revolution”. However, contrary to the government’s expectations, the election unfolded as a profound repudiation of Chavismo, with the electorate decisively rejecting the incumbent’s authoritarian revolution across states. Voting data published by the opposition shows that Edmundo González Urrutia, the opposition candidate, received 67.1% of the votes compared to 30.4% for Maduro.

Why did the opposition win this time?

High-ranking government elites were confident they would secure another victory, as they have over the past 25 years. Chavismo has filled state institutions with loyalists, coup-proofed the military, repressed dissent, and developed a counter-intelligence apparatus to address any external threats. In short, they have tilted the playing field entirely in their favour. Relying on their “big data“, clientelistic networks and employing tactics of intimidation, the ruling party trusted their local brokers to successfully mobilize the chavista bases on election day.

Yet, the election results revealed the stark disconnect between the ruling elite and the generalized discontent and harsh realities faced by ordinary citizens, particularly in low-income communities across the country. Years of economic mismanagement, rampant corruption, unseen levels of inequality, and a deteriorating public health and education system have eroded the quality of life, diminished the trust in the revolutionary ideals once championed by Chávez among its followers.

The wide margin by which the opposition secured a victory in authoritarian Venezuela highlighted a cross-class dissatisfaction and collective yearning for change. Despite the government’s efforts to split the opposition vote among other candidates, voters recognized that change required concentrating their support on González Urrutia. This understanding explains why other candidates received only 3% of the total vote. The high voter turnout, on average at 60%, and the coordination across communities before and during election day illustrate the decisive rejection of the ruling party and the high risks Venezuelans were willing to take to vote the ruling party out. Turnout could have been even higher if Venezuelans who left their country were allowed to update their voter registry from abroad. However, the government imposed significant barriers for these voters, effectively preventing many from participating in the election. This tactic excluded a substantial portion of the electorate, many of whom might have supported the opposition.

Despite deep-seated divisions rooted in strategic preferences, ideology and personal rifts, as well as divide-and-conquer strategies employed by the government, traditional opposition actors managed to coordinate around a joint candidate, González Urrutia, who replaced Maria Corina Machado, the winner of the 2023 opposition primaries. Machado, like dozens of opposition politicians, had been disqualified from running for office. Yet, in spite of her past strategic choices, Machado and other hardliners returned to the “electoral path” to pursue regime change. Machado, who previously advocated for boycotts and regime change through external pressure, made a strategic turn that proved essential in building momentum for the opposition. Her shift to participating in the electoral process and focusing on developing domestic capacities resonated with a population eager to vote the incumbent regime out. Shifting the focus to domestic efforts for regime change was particularly important after the internationally backed “interim government” led by former legislator Juan Guaidó failed to unseat Maduro and created more dilemmas for the opposition.

During her campaign, the opposition capitalized on widespread discontent with poor living conditions and citizens’ preference for pursuing a peaceful change through elections. Machado de-emphasized her right-wing ideology and shifted her focus toward issues affecting voters across socio-economic backgrounds. Her messaging centered on promises of economic reforms aimed at stabilizing the economy and improving the quality of life. Perhaps the most compelling mobilizing message was her pledge to bring Venezuelans back home. With almost 8 million citizens living abroad, Venezuelan families endure significant emotional and psychological grievances due to forced separations created by the ongoing crisis.

Anticipating potential fraud, the opposition reported to have deployed poll watchers to 99% of the voting centers on election day. This was the first time that opponents managed to cover polling stations across the country, despite facing repression and harassment. In contrast to previous elections, where opponents could not always provide clear evidence of fraud, this time they implemented a meticulous process to do so. Despite the risks, poll watchers scanned digital copies of the voting tallies in secure locations to prevent tampering or loss of evidence. This parallel tallying effort allowed the opposition to compile over 80% of the voting data. Collecting voter tallies was crucial in being able to counter the official results announced by the National Electoral Council (CNE). Only one day after the election, the opposition presented their findings to domestic and international audiences, demonstrating the government’s fraud and calling for a transparent audit of the election results. This strategy of independent tallying and request for verification has galvanized domestic and international support for Venezuelans’ demand to respect the results.

What does the voting data reveal?

To understand voting patterns in the current election cycle, it is essential to recall the historical context of chavismo’s strength over time. Initially a mass movement, Chavismo heavily relied on the charismatic leadership of Hugo Chávez and significant oil revenues to mobilize citizens. At the height of his popularity, Chávez achieved approval ratings exceeding 65%. In contrast, Nicolás Maduro has faced persistent disapproval, with rejection rates hovering around 80% for many years in a row.

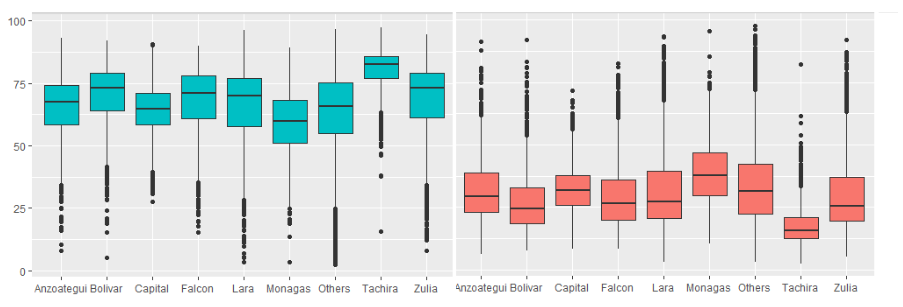

We analyzed the difference between Maduro and Gónzalez Urrutia across the country zooming into municipal level voting data for this presidential election. Overall, we can observe that the difference is high on a country level. The opposition candidate Gónzalez Urrutia won by a landslide with an overall participation around 60% across states. Zooming into regional dynamics, the biggest difference between the two candidates was in Táchira, while the lowest in Monagas (Figure 1 with state comparison ). Moreover, we see two distinct level of votes between two candidates, Gónzalez’s vote distribution barely touches Maduro’s level in all of most populated states.

Figure 1. Percentage vote distributions for Gónzalez (turquoise) and Maduro (red) by most populated states (REVIEW)

Data source: https://ganovzla.com/. Chart by authors.

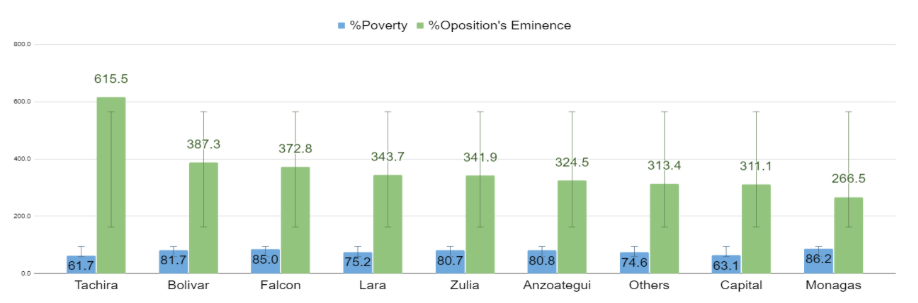

To understand how socio-economic conditions shaped voting behaviour, we analysed poverty data on a municipal level (271 cities) collected by ENCOVI in 2021. We used the percentage of the population living in extreme poverty (Figure 2) and verified the variation of this indicator among the most populated states across the country. Within the observed boundaries, there is a clear trend of higher votes for the opposition candidate, even when considering other variables. When analyzing the states as aggregated units, the opposition candidate consistently received at least 266% more votes than Maduro (i.e., 1.6 times more votes than the incumbent), regardless of poverty levels around voting locations (Figure 2). This widespread victory is particularly remarkable given the risks of repression, intimidation, the widespread presence of regime-friendly “colectivos,” and the sociopolitical control exercised by the incumbent over underprivileged communities. Notably, in Táchira Maduro would have had to multiply his voting capability more than 5 times to match the opposition’s vote).

Figure 2. Percentage of people living in extreme poverty alongside the percentage of additional votes Maduro would have needed to match the opposition’s total votes

Data sources: Encovi Project; https://ganovzla.com/. Author’s calculations.

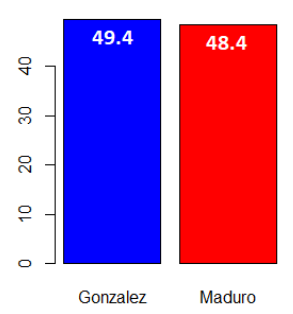

Socio-economic vulnerability and high voter turnout may suggest that state control and intimidation may have influenced vulnerable voters toward a ruling party vote. Nonetheless, when disaggregating the data and focusing on ballots from communities with the highest levels of extreme poverty and the highest turnout rates (Figure 3), the preference for the opposition candidate remains evident. This highlights the desire for change among the most vulnerable groups who lack the resources to finance the privatization of everyday life imposed by the government. It also underlines that Chavismo has lost its previous support over underprivileged groups. This voting behavior has unleashed a new wave of repression and tight control over these communities, indicating the government’s efforts to reassert its dominance amidst growing opposition.

Figure 3. Share of votes just in Voting centers (507) with the highest levels of extreme poverty and

electoral turnout combined

Data source: https://ganovzla.com/. Author’s calculations.

In conclusion, despite relying on the support of authoritarian allies abroad, specialized coercive forces, regime-friendly armed groups, surveillance mechanisms, 19 governors, over 200 mayors, co-opted opposition figures, and control of all state institutions, Nicolás Maduro failed to secure victory against opposition candidate González Urrutia. Asphyxiated by Chavismo and its policies, voters turned out in large numbers to cast their ballots for González on July 28th, even in remote and underprivileged communities. Despite facing numerous obstacles and an uneven playing field, people’s collective frustration culminated in a decisive victory for the opposition, underlining the role of institutional strategies in pushing back against authoritarian rule. Although the government has relied on fraud to maintain power, exposing the regime’s vulnerability at the ballot box has triggered tensions within the ruling coalition, low-rank defections, international alignment on pressuring the government, and a new politicization among Venezuelans, particularly among the youth.

Although the current situation in Venezuela poses significant challenges for researchers, given the risks of repression or the lack of reliable public data, engaging in collaborative data collection seems essential. In this way, scholars will be able to unpack when, why and how societies organize and resist under the most adverse circumstances.