Aline Burni

Between 6-9 June 2024, nearly 360 million Europeans were eligible to vote across the 27 Member States to elect the 720 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). These newly elected MEPs form the 10th legislature of the parliament for a mandate of five years. Although the European Parliament (EP) has more limited powers than a typical national parliament, it remains a relevant European body, responsible for supervising EU institutions, establishing and approving the EU’s budget, and passing legislation together with the Council based on proposals from the European Commission.

The EP elections are relevant not only to constitute this supranational assembly and translate voters’ preferences into a balance of power between the European political groups, but also to influence a series of events unfolding from the vote that determine the EU’s leadership, as well as the composition, alliances, and agenda of the next EU institutional cycle. The electoral results inform the nominations for the top EU jobs – the President of the European Commission, the President of the European Council, the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (the EU’s chief diplomat), and the President of the European Parliament.

European elections are typically referred to as ‘second-order’ because they are seen by voters as less relevant than national elections. They are usually driven by national issues and political dynamics, not European ones. However, this European vote triggered an unprecedented development at the national level, with French President Emmanuel Macron deciding to dissolve the National Assembly and call for snap elections scheduled to happen within a short period of three weeks following the European vote.

Despite concerns about a major rise of the far-right at both the EU level and in the French parliament, the results point to two general observations. First, even though the far-right continues its trend of gradual increase across Europe and in France in particular, it can still be contained, particularly if mainstream political elites coordinate among themselves and agree not to work with the far-right. Second, the centre seems to still hold, despite its shrinking size and reduced ability to build majorities. One can find evidence of both at the European and French levels. However, it also appears that the strategy of blocking the far-right may not be sustainable in the long run, because their vote share is expanding. Centrist parties need to transform the way democracy is functioning and delivering for its citizens in order to divert voters from supporting the far-right in their search for change.

A context marked by crisis, public dissatisfaction, and desire for change

Europeans voted in a context of high dissatisfaction, with the feeling of rising insecurity in multiple areas: the economy, society, climate, and geopolitics. Crises tend to offer fertile ground for populists and extremists. Over the last years, Europe has experienced subsequent crises – the 2008 economic turmoil, climate change, migration, Covid-19, the war in Ukraine, and the war in Gaza. As shown by a recent 12-country ECFR poll, the public was dissatisfied with how the EU managed these crises, with over 37%, on average, assessing the EU played a negative role. Over 70% thought the EU has done a bad job in handling the immigration crisis, 61% climate change, and 49% Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As the European elections approached, economic issues gained prominence in voters’ minds, with pressing concerns like rising prices, the cost of living, and social inequalities topping their agendas. Despite country-level variations, in general economic issues came ahead of topics like climate change and immigration, representing four out of the top five topics Europeans believed should be the highest priorities for incoming decision-makers, according to recent polls. The public was looking for change.

Against this prevailing climate of dissatisfaction, far-right parties were polling first or second ahead of the European vote in relevant countries like Austria, France, the Netherlands, and Germany, while a soft Eurosceptic party (Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia) was polling in first place in Italy. Until April 2024, the far-right group Identity and Democracy (ID), which included the French Rassemblement National and the Italian Lega, was emerging in third place, ahead of the liberal group spearheaded by Macron, Renew Europe (RE). However, the German party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) was expelled from the ID group following scandals affecting the party, including accusations of connections to China and Russia. Overall, the expectation right before the 6-9 June vote was one of an unprecedented gain by far-right parties at the European level.

The EP elections remain driven by national politics and dominated by national issues. In many cases, those elections have worked as a referendum against the national government. However, this time cross-border and global issues were more present in voters’ minds, especially given the wars at Europe’s doorstep and the climate emergency, although they were not dominant. To some extent, domestic politics have also been ‘Europeanised’. This was especially the case in France, where the disappointing results obtained by Emmanuel Macron’s party in the European vote triggered the dissolution of the National Assembly and the call for snap elections in France.

European results: a swing to the right, pro-EU parties holding a slight majority, and limited gains for the far-right

The European elections usually do not strongly mobilise voters. Often referred to as ‘second-order’, they have lower importance than national elections in the eyes of voters. Turnout tends to be low, usually around 50% on average. In 2019 and 2024, turnout slightly increased. However, there was notable variation across Europe, with countries like Belgium (where voting is mandatory and turnout reached almost 90%), Luxembourg (82%), Germany (64%), Malta (73%), and Denmark (58%) voting above the European average in 2024. On the contrary, countries in Central and Eastern Europe tended to display much lower turnout, for instance Croatia (21%), Lithuania (28%), Bulgaria (33%), Slovakia (34%), and Poland (40%).

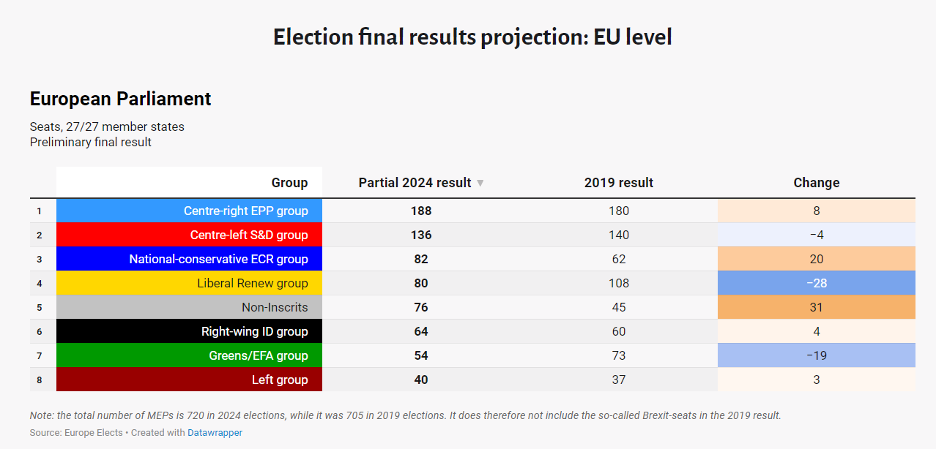

The results of the European vote were broadly in line with predictions, with the legislature shifting to the right. The centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) emerged as a clear winner and gained about 8 seats compared to 2019, becoming the new centre of gravity of the parliament. Far-right parties made some relevant gains, particularly in France and Germany, where the RN went from 22 to 30 seats and the AfD from 9 to 15, respectively. In addition to those countries, far-right parties arrived first or second in Austria, Italy, Poland, and the Netherlands. They made some gains, but overall, these were more limited than anticipated. For instance, the Austrian FPÖ went from 3 to 6 seats and the Dutch PVV from zero to 6. The Sweden Democrats (3), the Danish People’s Party (1), and the Belgium Vlaams Belang (3) kept the same number of seats as before. The Finns Party lost one seat. Far-right parties performed less well than pollsters predicted in Scandinavian countries, Spain, and Portugal. Nevertheless, the Portuguese Chega! went from zero to 2 seats, and the Spanish Vox doubled its previous 3 seats to 6.

Source: Europe Elects

The biggest populist radical right loss in terms of seats was Salvini’s Lega, but its decline was matched by the rise of Meloni’s FdI (24 seats in total). The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), ID, and the non-aligned (NI) groups have gained seats. It’s relevant to note that about 42 out of the 77 non-aligned elected MEPs fall into the far-right/national conservative category, chief among them the AfD and the Hungarian Fidesz. Far-right groups are far from becoming a majority, but this does not mean they are irrelevant. The picture was one of general stability in most countries, significant gains in France and Germany, and a gradual increase in the European scene, continuing a trend over the last decades.

The centre-left bloc experienced the biggest losses. Although the parties in the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) group managed to remain second and maintained about the same number of seats as before, Macron’s Renew Europe group and the Greens/European Free Alliance group lost around 20 seats each. In the case of Renew Europe, the election outcome caused it to lose the third position in the EP to the ECR. These losses were mainly driven by poor results in France and Germany, the largest Member States. However, there were important nuances across Europe, with the Greens performing relatively well in the Netherlands and Denmark, and the Social Democrats in Portugal and Spain, for instance.

The Europeanisation of French politics? Snap elections following the European vote

The results of the European elections were very close to the projections. The biggest surprise of the night was Macron’s decision to dissolve the National Assembly and call for snap elections in France. For the first time, the outcome of a European election had such major repercussions at the national level. Macron’s decision was prompted by the significant rise of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (31%), which obtained twice the vote of Macron’s list (14.6%) for the European Parliament. The latter lost almost 8 percentage points compared to 2019, falling from 21 to 13 seats in the EP, while the RN became the biggest single party delegation with 30 seats.

There were several attempts to explain Macron’s decision on the night of June 9. He himself said he wanted ‘clarity.’ Several analysts interpreted Macron’s decision as a bid to re-establish himself as the only credible alternative to the RN, relying on the assumption that a majority of French people would reject the far-right in office. But the president’s popularity had fallen to just 26% ahead of the dissolution. This strategy was seen as extremely risky in Brussels. The perception of whether this approach could work or backfire, potentially opening the doors of power to the far-right, changed dramatically between the first and second rounds of the election. In the end, Macron ended up with a hung parliament, and at this stage, it remains uncertain who will govern France in the coming months.

Results in France: an unexpected surge of the left, a blocked far-right, but a hung parliament

On the night of 30 June, after the first round, the RN seemed poised to win. The party, founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972, found itself in a position where it could envision forming a government for the first time. Polls showed the RN clearly leading across France. In a historic rise, the party received around 10 million votes in the first round, corresponding to 33.2% of the national electorate. Furthermore, it managed to elect 37 deputies in the first round, with those candidates securing more than 50% of the votes. The RN came first in 297 districts, and initial projections placed Marine Le Pen’s party in a position to win between 255-295 seats in the second round. This represented a real and unprecedented chance to not only drastically increase its presence in the National Assembly but to obtain a majority and form a government. The plan was to have the president of the RN, Jordan Bardella, appointed as Prime Minister.

The two-round French system allows more than two candidates to run in the second round of a legislative election. This is because all candidates who obtain support of at least 12.5% of the registered voters have the chance to run in the second round. When a run-off features three candidates, it is called a ‘triangulaire’. This time, the outcome of the first round indicated more than 300 ‘triangulaires’ could take place, compared to only eight in 2022. However, in light of the extraordinary situation where a far-right majority seemed possible, both Macron’s Ensemble coalition and the left-wing New Popular Front (NPF) quickly mobilised to reduce the chances of an RN victory. In practice, this meant massive withdrawals of third-placed candidates by these two coalitions to present a single alternative against the far-right candidate. Withdrawals to block the far-right occurred in about 220 cases, among which 82 were from Macron’s coalition and 131 from the New Popular Front.

Against all expectations, the left-wing bloc emerged ahead on 7 July, winning 182 seats. Macron’s coalition followed with 168 seats, while the RN and its allies came in third with 143 seats. Nevertheless, the RN achieved a historic result, considerably growing from its 88 seats in the outgoing parliament within an electoral system designed to keep the extremes out of power.

Three main factors seem to have contained the rise of the RN and reversed its chances of winning a majority. First and foremost, tactical voting induced by the withdrawal of NFP and Ensemble candidates made voters hostile to or concerned with a far-right government support the only viable alternative, either from the left or the centre. Second, the high mobilisation of the electorate, linked to the apprehension of a possible far-right government, contributed significantly. Turnout was very strong in both rounds (66.7% and 66.6% in the first and second rounds, respectively). This was the highest second-round turnout since 1997, when Jacques Chirac dissolved the Assembly. Third, Emmanuel Macron’s absence from the second-round campaign allowed candidates to focus on the narrative of containing the far-right without having to associate such a choice with personal support for Macron, which would be a challenge given his unpopularity among French voters.

No clear majority emerged from the French vote, leaving enormous challenges ahead for the formation of the next French government. The National Assembly is split into three strong camps – none of them getting even close to the 289 required to form a majority – that can hardly find common ground on any major issue. The electoral battle against the far-right might have succeeded once again, but it remains unclear what will unite a potential governing coalition next, given that the ‘republican front’ built in the elections is extremely unlikely to stay alive to constitute a government.

After the challenge of elections, the challenge of government

The results of both the European Parliament and the French National Assembly elections are in. They are different from one another. However, the full picture of the new hemicycles and the governments emerging from them is still to be completed.

In the European Parliament, party groups reorganised themselves, and two new far-right groups emerged alongside the existing ECR: Patriots for Europe – a rebranding of the previous ID which now includes Viktor Orbán’s party – and the Europe of Sovereign Nations group, organised around the German AfD party, and gathering parties which are against supporting Ukraine.

So far, more centrist, pro-EU groups have resisted the pressure from the far-right by creating an alliance between themselves to reappoint Ursula von der Leyen as President of the European Commission and to exclude the far-right groups from key positions in the European Parliament – despite their size. Furthermore, EU leaders agreed to nominate candidates from the three mainstream groups (EPP, S&D, and Renew) to the three top jobs, indicating that they are willing to continue working together. Von der Leyen managed to negotiate support from the pro-EU parties based on policy and job compromises, including the Greens/EFA, to get elected, instead of reaching out to the ECR. One of the conditions of the pro-EU partners was that the EPP would not collaborate with the groups on the far-right.

Greater efforts will have to be made in the case of France to build a majority or even a minority government, as Macron’s coalition has considerably decreased from 250 to 168 seats. On one side, after a period of intense disagreement within the left-wing NFP to propose a candidate for prime minister, Macron has refused to give the left a role to try to form a government. On the other side, the centre remains in a pivotal position to form a government, although it is now squeezed between a sizeable far-right and a radical left, with which it has very little in common. Both the left and the right sides refuse to work together or to enable a government led by the other. Moreover, French political culture is not one of consensus-making, and all leaders are watching the 2027 presidential elections.

Conclusion

Many recent examples—from Poland to Brazil—have shown that it is still possible to block the far-right’s access to or maintenance of power when mainstream parties coordinate their actions and unite against the far-right. However, in the long term, this strategy may no longer be feasible. If the far-right continues to grow electorally, it becomes an increasing challenge to contain its access to decision-making and influence on policies.

The question now is how long this strategy can work and whether centrist parties – in a broader sense – will still hold. Mainstream parties must use their time in office to implement democratic reforms and deliver policies that improve the lives of citizens and address their priorities, especially by establishing trust in the functioning of liberal democracy. It does not seem wise to simply open the door to the far-right and expect voters to judge its incompetence to govern. It might be too late to regain power after the far-right curtails institutional checks and balances and weakens liberal democracies, as often happens. The best strategy at this point is to keep the far-right away from power and at the same time lead the urgent and necessary reforms to improve liberal democracy and provide tangible results to citizens.