Ryan E. Carlin, Laura Beghini Chelidonopoulos and Gabriel Miller

Should he lose his re-election bid, many observers expect Jair Bolsonaro to propagate a Big Trumpian Lie and spark an event reminiscent of the January 6 insurrection. But subverting the popular would be much riskier under two scenarios; (1) if ex-president and challenger Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva wins decisively; and (2) if Brazilians forcefully embrace democratic principles and norms. These scenarios are not mutually exclusive and, we posit, could be related.

In this essay, we explore links between election outcomes and democratic support. Our theoretical framework marries strains of macro-opinion research on policy preferences and democratic preferences through a thermostatic model. We conduct a plausibility probe of this model by analyzing the interplay of democracy and public opinion in Brazil over the last two decades. Our theory expects that, just as Brazilians rejected the democratic status quo by electing the illiberal Bolsonaro in 2018, a growing backlash against democratic backsliding could deny his re-election in 2022.

From Macro Polity to Macro Demos

According to the theory of representation advanced in The Macro Polity, public preferences for a bundle of issues move in parallel over time. This creates a “policy mood” which, in the United States, ranges ideologically from “conservative” to more “liberal.” Policy mood responds to public policy outputs (i.e. laws promulgated and spending outlays) in a thermostatic fashion: when policy outputs tilt too liberal, policy mood swings conservative. When, in turn, public policy tends too conservative, policy mood shifts liberal.

Normatively, such dynamics are welcome new because they incentivize candidates to anticipate the trajectory and location of citizen preferences. This enhances overall political representation. Theoretically, policy mood is not merely a description of public opinion. Indeed, policy mood swings better predict election winners than more conventional predictors (e.g., the economy, partisanship). Macro-political theories of representation, thus, suggest the democratic ideals of accountability and responsiveness are achieved in the aggregate.

Scholars have adapted this macro-polity framework to explain fluctuations in mass preferences for democracy, or “democratic mood.” And like their macro-polity forebears, macro-demos researchers find evidence that democracy levels and democratic mood also conform to thermostatic dynamics: democratic expansion tends to lower public preferences for democracy. Democratic erosion, however, can improve citizens’ democratic preferences. Hence, democratic mood swings correspond to changing democratic outcomes, just as policy mood swings correspond to shifts in policy outputs.

Democratic Mood and Election Outcomes

Whereas policy mood’s electoral implications are well documented, democratic mood’s are not. In the macro-polity literature, elections are won by leaders whose ideological stances best match the electorate’s policy mood. From a macro-demos perspective, might candidates whose democratic stances most closely reflect the electorate’s democratic mood be expected to fare similarly?

A full theoretical treatment and rigorous empirical test are well beyond the scope of this essay. Yet combining macro-polity and macro-demos to understand election outcomes does not seem far-fetched. In addition to thermostatic dynamics between democracy levels and democratic preferences, evidence suggests that publics in newer democracies punish incumbents for undemocratic behavior. The key question, we submit, is under what conditions might mass democratic preferences shape election outcomes?

Rather than an exhaustive list, we identify a necessary, if not sufficient, condition: the election must pit a pro-democratic candidate against an anti-democratic candidates. When the electorate is on an upswing of democratic mood, it should favor the pro-democratic candidate. Conversely, when democratic moods ebbs, anti-democratic candidate should have the edge. A more formal study would need to conceptualize “pro-democratic” and “anti-democratic” in a rigorous way. To justify our case selection of Brazil, we now consider the following contextual elements.

Pro- and anti-democratic stances have defined the 2018 and 2022 Brazilian presidential elections. Jair Bolsonaro’s 2018 campaign employed chauvinistic and homophobic tropes, criticized democratic institutions, and deployed fake news against his opponents. His 2022 campaign seeks to undermine faith in the election system and to delegitimize the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) that oversees the lawful execution electoral rules. If and how the military will participate in the electoral process – at Bolsonaro’s behest – remains an open question as of this writing. Coup rumors circulate widely, even as Bolsonaro downplays them. As for the Big Lie, Bolsonaro maintains that he will accept the election outcomes so long as they are clean—by his standards, not necessarily those of the TSE. Lula, for his part, has spoken out on many occasions to quell fears of a coup, to support pro-democracy acts, and to bolster democratic institutions. Lula’s message has been consistently pro-democracy, though he often elides democracy as liberal institutions and rule of law with democracy as social progress.

In short, Brazil’s 2022 presidential election arguably fits the conditions under which we might expect democratic mood to influence electoral outcomes. Equally important, is rigorous panel and cross-section evidence from Brazil’s 2018 presidential election that suggests Bolsonaro voters were more likely to exhibit flagging democratic preferences and greater illiberal preferences. Such evidence is wholly in keeping with the first mechanism of our theoretical framework: falling democratic preferences electorally benefit anti-democratic candidates. As we show below, democratic mood and democracy levels exhibit a thermostatic dynamic and, moreover, democratic mood is presently on a clear upwards trajectory.

Democratic Thermostatics in Brazil

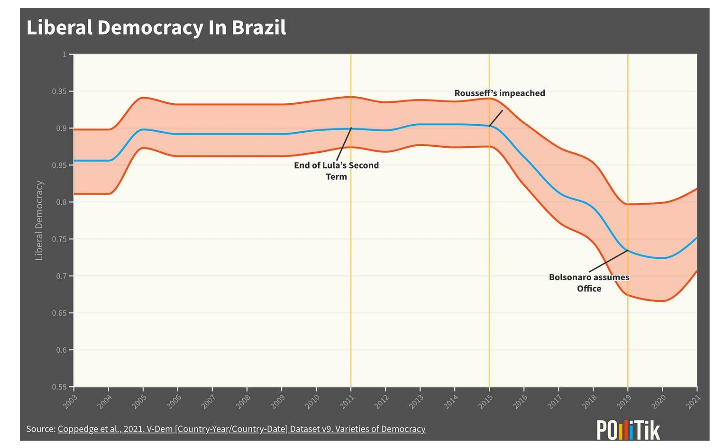

Our discussion of democratic thermostatics in Brazil begins with an analysis of its Liberal Democracy Index provided by Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem; see graphic below) from 2003 to 2021. We observe a degree of democratic backsliding after the presidency of Dilma Rousseff: the commodity boom had ended, corruption associated with the Lava Jato scheme had thoroughly ensnared the political class, congress had impeached Rousseff, and a polarized Brazilian public had been protesting a range of social-political problems. Jair Bolsonaro’s campaign leveraged this “perfect storm” to the presidency, which began January 1, 2019.

Liberal democracy continued its downward trajectory until rising in 2021. Bolsonaro’s attempt to achieve herd immunity during the COVID pandemic threatened rights to health and human safety. A congressional panel later condemned his policy as a crime against humanity. All the while, Bolsonaro routinely abused journalists and attacked the TSE and the Supreme Federal Court, as well as individual members of both. Bolsonaro and his coterie regularly authored and diffused fake news and misinformation. Looser gun laws, promoted by Bolsonaro, raised Brazilians’ fears for their rights and safety. Indeed, Bolsonaro defended the use of excessive force to quell protests and to police favelas. Violence between political rivals increased to record levels and turned bloody on several occasions.

The 2021 rebound in the Liberal Democracy Index probably reflects the TSE’s and Supreme Federal Court’s willingness to hold Bolsonaro accountable for some of his most egregious transgressions. For example, the Supreme Federal Court countered Bolsonaro’s laissez-faire approach to the coronavirus by emboldening state and local governments to implement policies to slow the spread and enhancing protections for indigenous communities. The TSE has combatted accusations that seek to undermine Brazilians’ faith in the electoral process.

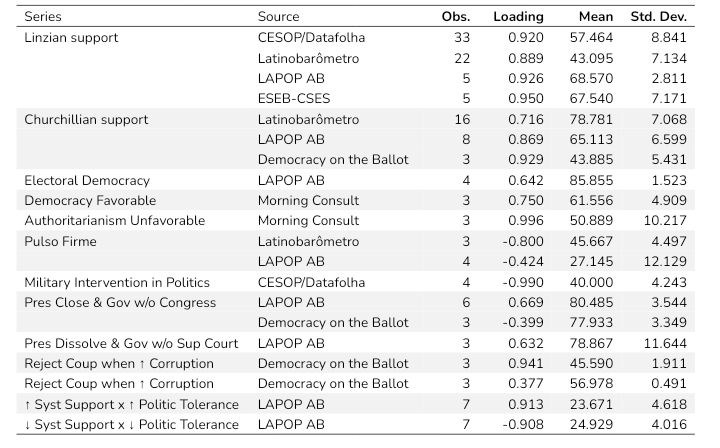

We measure democratic mood by combining twenty aggregate time series of democratic preferences over 33 years of public opinion surveys on national samples of Brazilians. Our dataset consists of series from AmericasBarometer, the Brazilian Election Study, Datafolha, the Democracy on the Ballot Panel Study, Latinobarômetro, and Morning Consult[1].

Table 1. Democratic Mood Input Series, 1989-2022

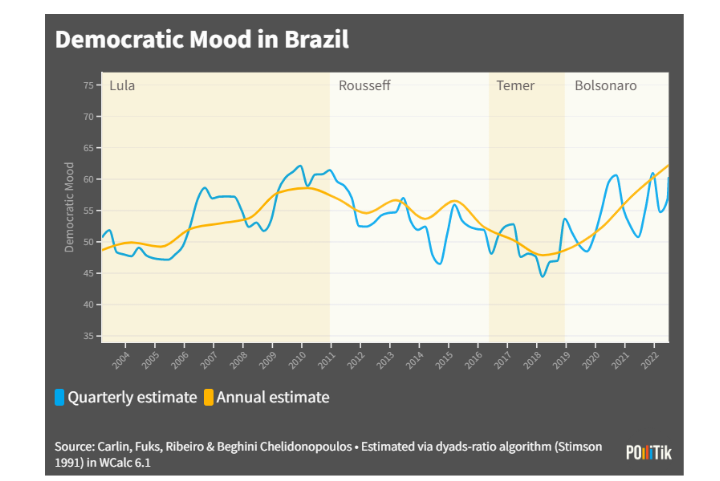

Figure 2. Democratic Mood in Brazil, Quarterly and Annual Estimates, 2003-2022

To combine these indicator series, we follow macro-polity research and employ the dyads-ratio algorithm. This method is analogous to time-series factor analysis. It main advantages are that it can deal with missing data and, in turn, use communality estimates to impute values at specified intervals (e.g., year, quarter, month; see Stimson 2018 for a detailed account).

Figure 2 presents democratic mood the period of interest, 2003-2021. Annual estimates trade temporal precision and variation for more information (i.e., data). Quarterly estimates vary more over time but draw on fewer data points per period. Trends are, nevertheless, consistent across the quarterly and annual estimates.

After high and sustained levels on the Liberal Democracy Index in the 2000s (see Figure 1), we observe an illiberal backlash (see Figure 2). That is, democratic mood decreased from Rousseff’s ascent in 2011 until Bolsonaro took office in 2019 – with a brief upturn around elections in October 2014. Levels of democracy bottomed out in 2020, during Bolsonaro’s government. But by mid-2018, we observe a backlash against democratic backsliding, i.e., democratic mood its reversed course and began climbing again. As thermostatic theory would predict, by 2021 democracy levels began to recover[2].

Although our preliminary analysis does not control for confounding factors, it reveals patterns in line with prior studies that do. In sum, democracy levels and democratic mood in Brazil replicate the expected thermostatic relationship of extant macro-demos research. But can we graft these dynamics onto the prediction, from the macro-polity literature, that an upswing in democratic mood should favor a democratic challenger over an anti-democratic incumbent?

Democracy is on the Ballot Again

We expect a pro-democratic mood swing could, as in 2018, hold electoral implications in 2022. But now that the pendulum of public sentiment has swung back in the democratic direction, our prediction is that the pro-democracy candidate, Lula, holds an edge over the illiberal incumbent, Bolsonaro.

At this point in the race, all empirical evidence suggests this is the case. A Datafolha poll, fielded September 13-15, found Lula leading Bolsonaro in the first-round vote intentions, 45% to 33% (± 2%, 95% c.i.). An IPEC poll fielded September 17-18 indicated a lead of 47% for Lula over 31% for Bolsonaro (± 2%, 95% c.i.). Forecasts by Polling Brazil project Lula to win 39% of the round-one vote, and Bolsonaro to win 37%, as of this writing. Polling Brazil also assigns a 100% probability to the chances of a runoff election, in which they predict 49% for Lula and 40% for Bolsonaro.

Of course, these outcomes are over-determined. Non-rival factors are likely at play – inflation, unemployment, ideological and affective polarization, etc. – as research on Brazil’s 2018 election has found. Yet incumbent presidents hold myriad advantages over challengers, and their re-election rates are upwards of 80%. Such a track record suggests that incumbents – seemingly against all odds – tend to weather economic crises, to withstand scandals, and to wiggle out of all kinds of binds. Simply put, re-election-seeking incumbents are difficult to stop. Therefore, Lula’s polling advantage would be somewhat more puzzling without considering democratic mood. He is challenging an illiberal incumbent who had presided over democratic backsliding at a time when Brazilians are renewing their pledges to democracy.

We believe the evidence from Brazil’s 2018 election plus the dynamics we report here warrant further investigation. Moreover, the validity of our theoretical framework hinges on gaining better control over the variables at play, addressing measurement uncertainty, and expanding generalizability. If data exist, our expectations could also be tested in the 2020 US elections in which Joe Biden defeated illiberal incumbent, Donald Trump. And if Trump challenges Joe Biden in 2024, it will yield yet another test. An eventual re-election bid for El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele is another potential case. Laws against re-election rule out tests in Mexico and Guatemala. And, of course, we await confirmatory evidence from Brazil, where the presidential race is far from over.

[1] Data originally compiled by Mario Fuks and Ednaldo Ribeiro; updated by Laura Beghini Chelidonopoulos, Gabriel Miller, and Ryan Carlin. We thank Matthew Kendrick at Morning Consult for sharing data. The dataset remains under construction and estimates are still undergoing validation. Please contact the authors for more information.

[2]Carlin, Fuks, and Ribeiro (2022) reach a similar conclusion in their working paper, “The Dynamics of Democratic Support in Brazil,” (available upon request).