Aline Burni

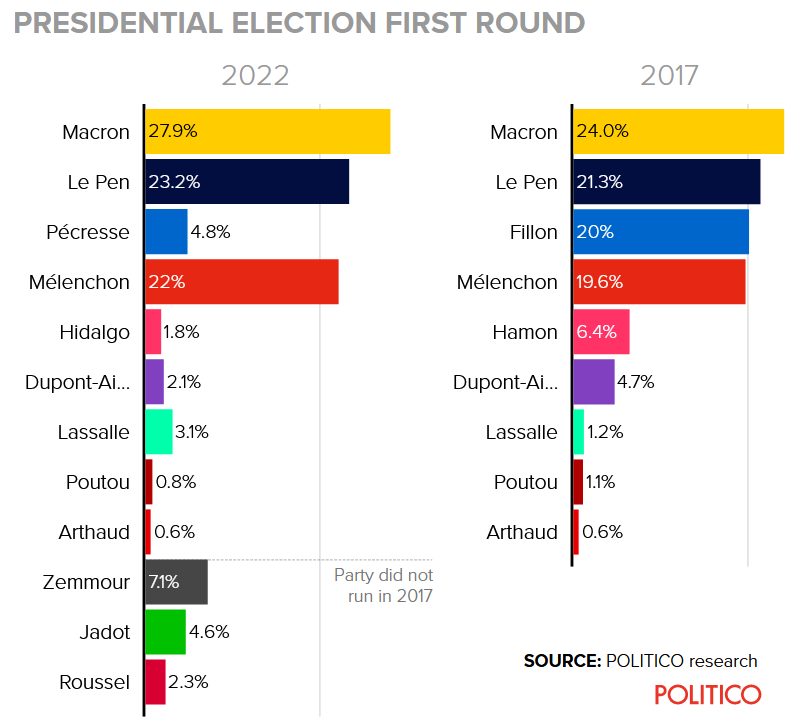

On Sunday 10 April, the French citizens voted in the first round of presidential elections. The results have set a four-point advantage for incumbent Emmanuel Macron (La République En Marche, LREM) over the second-placed far-right candidate, Marine Le Pen (Rassemblement National, RN) (see graph below), against whom the current president will run the second round on 24 April[1]. However, although Macron remains favourite to win, the election outcome also shows that the race between the two remains considerably tight – to the point where Le Pen has, for the first time ever, a realistic chance of winning. In fact, her party has never been so close to power. Featuring a noteworthy number of running candidates (12 in total), high voter uncertainty and volatility, this race will define the fate of France and Europe amidst a series of unsettled crises (e.g. the COVID-19 pandemic, the yellow vests protests, the Russia war on Ukraine). Not only the re-election of Macron is at stake, but also the prospect of traditional parties and politicians, as well as the future of the (populist) radical right, a persistent force in France for decades now. The presidential election has been characterised by an unusual campaign, with extraordinary voter apathy. Some of its main takeaways can be summarised as the further erosion of the French party system, yet the lack of the emergency of a (new) structure of political competition, as well as the persistent strength of radical forces, both on the left and on the right of the political spectrum.

Source: https://www.politico.eu/article/5-takeaways-from-frances-presidential-election/

An unusual campaign

It has been an unusual presidential campaign, in several aspects. Although it was not a secret that Macron would stand for re-election, he officially declared his candidacy very late in early-March – at the very last minute. This has led to accusations against him of insufficient commitment to campaigning or taking unfair advantage of the presidential office. By the public, Macron was seen as more ‘president’ than ‘candidate’ and as distant from the average citizen. In addition, the incumbent avoided participation in some media interviews and debates with other contenders. Over the last weeks of the race, he often appeared to be ‘too busy’ with the Russia-Ukraine war.

It was a race marked by apathy and high indecisiveness among voters. In February 2022, eight out of ten French people rejected the announced competition between Macron and Le Pen for the upcoming second round, even though 59% were convinced this would eventually happen. Having the 2022 elections in mind, 72% did not see any political personality that would suit their preferences. Overall, more than 30% were unsure whether to vote at all and for whom, until the last minute. Also, it is difficult to identify a clear dimension or issue that dominated the electoral campaign. While in the early days the topic of COVID-19 mandatory vaccinations still held some relevance, the pandemic became virtually absent from the race.

To a relevant extent, the Russia military invasion of Ukraine in late-February became a striking topic, although mostly due to its indirect effects in France and Europe. First, Macron benefited from the classical ‘rally around the flag’ effect, rising to 30.5% on vote intentions in early-March. However, such an effect did not last for more than a month. Marine Le Pen, a long-time admirer of Russia’s Putin, who even lend money to her party, could have been caught up in the Russia-Ukraine conflict because of her pro-Putin stance, but she has managed to dodge criticism by condemning the war very early and by focusing on purchasing power.

By its turn, issues dominating latest elections, such as immigration, security and identity, have given place to other major concerns of French citizens, in particular purchasing power, the reform of the retirement system, and public health. In effect, the topic of immigration was only around the fourth most important in 2022, behind social security, climate change, and purchasing power. Curiously, the prioritisation of the environment by more than 20% of the electorate, has not led to its prominent presence in the political debate and the green candidate Yannick Jadot did not manage to poll above 5%.

As a final point, it seems that tactical voting has played a non-negligible role over the final results – to different extent for all three better placed candidates – Macron, Le Pen and Mélenchon. While the TV celebrity and journalist Éric Zemmour promised to be a surprise when he launched his movement Reconquête!, in the end it was the better known and more experienced radical candidates Le Pen and Mélenchon who managed to recover support and consolidate their scores. With other left-wing candidates displaying pitiful results in the polls, Mélenchon played the ‘tactical voting’ card and called citizens to vote for him in order to avoid having to choose between Macron and Le Pen in the second round. By her turn, Marine Le Pen won (back) right-wing voters around her – from both Zemmour and some from Pécresse (Les Républicains, LR), who were seen as less capable of beating Macron.

Further erosion of the French party system: the old is gone, but the new is yet to come

Mirroring the drastic erosion of the traditional centre-left Socialist Party in 2017, the first round of 2022 was marked by the defeat of the centre-right LR, with its candidate Pécresse scoring only 4.8%. For decades, the Fifth French Republic has been characterised by the hegemony of two competing and alternating blocks: the centre-left and the centre-right, which used to gather up to 80% of voters’ preferences and have alternated in the government for several years. Already the 2017 presidential election represented a turning point in French electoral politics, marked by the meagre performance of the main governing parties’ candidates and the victory of a political newcomer at the time, Emmanuel Macron. By then, the PS scored only 6.4% of the votes, while LR was still breathing some life with 20% of support for candidate Fillon. In contrast, in 2022 the sum of Pécresse (LR) and Hidalgo (PS) not even reached 10%, which consolidates the drastic erosion of the traditional party-system. In part, such de-alignment can be explained by the increasing distrust and apathy of voters, who no longer systematically place themselves on the classical left-right ideological dimension.

The similarity of the numbers conquered by Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon between 2017 and 2022 can be misleading in light of the phenomenon of electoral de-alignment. They could lead to think these three leaders as being the new structuring forces of the political system. However, the erosion of the traditional party system cannot be said to have already been replaced by a new configuration of political forces, less so by a new configuration of parties. In fact, what we see gaining ground are the emergence of movements organised around individual leaders, instead of political party organisations. In addition, these three personalities are more likely to be in the end of their political ambitions, instead of the beginning of their careers. If re-elected, Macron cannot run again in 2027. Mélenchon and Le Pen, respectively at their fourth and third presidential elections, are expected to be trying their last presidential attempt this time, in 2022. The political elite itself has been quite volatile and disloyal regarding their party attachments. Macron formed his government with personalities coming from both the traditional centre-left and centre-right organisations, while the Rassemblement National lost some important party officials who decided to join Zemmour’s camp lately. Over the last years, the electorate has no longer been clearly structured along the lines of left-right ideology, but a new dimension of competition has not yet imposed itself in France either.

Although the repeated duel between Macron and Le Pen points to the relevance of a divide between a cosmopolitan side and a patriarchal side, it is too early to say that this will be the definitive structure of political competition for the years to come. There remains important incongruities between the dynamics of party-competition at different levels in France: local, regional, national and European. As political scientist Dominique Reynié correctly emphasised: today, the main forces around the presidential elections (Macron and Le Pen) do not have locally elected officials, while the traditional parties who no longer have national relevance, are still dominant in local office.

The strength of the radicals

Marine Le Pen and, especially Mélenchon have run an effective campaign on the ground and on the media, exceeding their projected vote share previously announced in the polls. Both have also increased their results compared to 2017 and managed to expand their electoral base to some extent. Their favourable dynamics can be explained by both long-term and short-term factors. As a matter of fact, Marine Le Pen has implemented a strategy to modernise, moderate her image and rhetoric for a decade now. In the short run, she benefited from the arrival of an even more radical and brutal rival, Zemmour. Mélenchon occupied the space opened up by the decadent left, he expanded the scope of his programme (appealing to issues like environment and climate) and rose in the polls in the final weeks by benefiting from being perceived as the only viable candidate on the left.

Nevertheless, the programme of both candidates remain radical. Marine Le Pen still fosters the discrimination of ethnic minorities and defends the ‘national preference’ to access public services like housing. She is also for the ban of headscarves, and for drastically limiting the arrival of immigrants and the access to the French nationality. Mélenchon proposed far-reaching institutional changes, including the foundation of a new Republic. In addition, he defends price blocks, and even ‘disobedience’ to European legislation if needed to implement his programme. Both are hostile to the European Union, by the way.

Therefore, the electoral results mainly confirm that the rising anxiety, ennui and mistrust of French people over the last years have been largely captured by anti-establishment and radical candidates, instead of moderates. The far-right bloc — Marine Le Pen, Éric Zemmour and nationalist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan combined — garnered more than 30% of the total vote. Combined with Mélenchon’s 22%, this sums up to more than half of the electorate going radical. Not only that – the radical candidates have mainly attracted younger voters. According to the vote preferences by age, 34% within the 18-24 and the 25-34 ranges voted for Mélenchon (against 25% for Macron and 17% for Le Pen, and 22% for Macron and 27% for Len Pen, respectively). Le Pen ranked first among those aged 35-49 and 50-64, receiving the vote of 29%. The only age range in which Macron won was those older than 65.

Final remarks

Already in the evening of the first round, main candidates endorsed Macron to prevent the far-right leader coming to power (Hildango, Pécresse, Jadot). Unsurprisingly, Zemmour is now supporting Marine Le Pen. Yet, Mélenchon indicated to supporters that ‘no vote should go to Marine Le Pen’, but has not actively endorsed Macron, leaving the door open, particularly for a massive abstention of his electorate. Recent polls show that almost half of Mélenchon’s voters could abstain in the run-off, while the rest are expected to split between Macron and Le Pen.

Due to its numeric relevance in the first round and the unclear command of the radical-left leader of the movement ‘La France insoumise’, Mélenchon’s voters will be decisive for the final results, as well as those 26% that abstained in the first vote. Macron was quick to signal towards the leftist supporters. In his first speech after the announcement of the results, he mentioned the defence of Universalist and culturally-open values, his pro-European Union stance, but also his commitment to purchasing power and to tackle other socio-economic concerns. His first campaign displacements targeted the regions where Le Pen has been traditionally strong, which are composed of more popular social sectors. As for Le Pen, she is challenged with the task of pursuing her moderation strategy, while raising her credibility to form alliances and govern the country. Although much weaker than in the past, it seems that the old ‘cordon sanitaire’ designed to block the far-right getting to power is still operating at the level of the political elites. However, it remains to be seen if it is also alive at the level of voters.

Notes

[1]Presidential and legislative elections in France are non-concurrent. The election of the 577 members of the National Assembly (lower-house) happen after the runoff and are scheduled to be held on 12 and 19 June 2022.