“Boys wear blue, girls wear pink”: Bolsonaro and the anti-gender agenda as government policy in Brazil

February 2, 2022

Daniela Rezende[1]

The Secretariat of Policies For Women (hereafter SPM) was founded in 2003, becoming the first agency in Brazil to have Ministry status and with political and financial resources to plan and implement policies for women. The SPM’s priority actions were those related to fighting violence against women and to promote women’s work and economic autonomy. It also aimed to consolidate and expand policies for women at other levels of public administration, providing technical and financial support for the creation of municipal and state women’s agencies and councils. In the 2010s it began to incorporate the demands and needs of rural women workers as a response to the pressures and mobilization of this group throughout the 2000s. In addition to greater resources, the SPM differentiated itself from previous experiences by investing in formal spaces for social participation, such as the National Council for Women’s Rights (CNDM) and the National Conferences on Women’s Policies (CNPM).

Regarding the relationship between the SPM and the National Congress, the Secretariat played a prominent role in articulating, together with the National Congress women’s caucus, the adoption of important legislation that guaranteed women’s rights, such as the Maria da Penha Law and Constitutional Amendment 72/2013, which deals with the labor rights of domestic workers. It also sought articulations with other policy areas in the Executive, such as the Ministries of Health, Education, Agrarian Development, and Human Rights and Promotion of Racial Equality, as a strategy of gender mainstreaming.

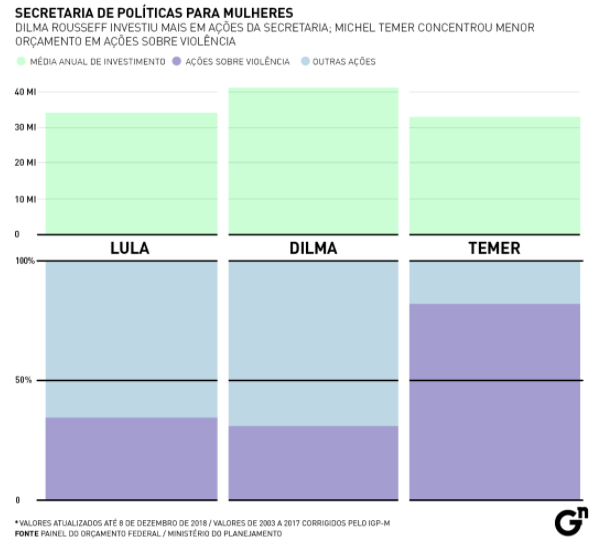

However, after the second government of President Dilma Rousseff, the SPM’s institutional capacity became limited, both in terms of scope and depth (Piscopo, 2014). In this scenario, in 2016, still in the Dilma government and in the context of a political crisis that culminated in the president’s impeachment, the agency lost its ministerial status and became linked to the Ministry of Women, Promotion of Racial Equality and Human Rights. Chart 1 shows the continuous decrease in the portfolio’s budget. Note that, despite the political crisis, the Dilma government (2011-2016) was the one that invested the most in women’s policies, when compared to the Lula (2003-2010) and Temer (2016-2018) governments. In the latter’s government, the portfolio’s budget was reduced to one third of the amounts allocated in 2010 or 2015, and in 2018, the portfolio’s entire budget was applied in policies to confront gender violence:

Graph 1: Budget and actions developed by the Secretariat of Policies for Women, 2003-2018.

Source: Gênero e Número, 2018.

Despite the trend of budget cuts and loss of status in previous years, it was in the Bolsonaro government that policies aimed at gender equality suffered the biggest setback, since the anti-gender agenda (or the agenda contrary to the so-called “gender ideology”) went from campaign platform to government policy (Aragusuku, 2020). The portfolio was renamed as Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights, which signals a conservative reorientation of its agenda, reinforced with the appointment of pastor Damares Alves[2] as minister.

Kuhar and Patternotte (2017, p.5) define “gender ideology” as a political discourse and transnational strategy, which “regards gender as the ideological matrix of a set of abhorred ethical and social reforms, namely sexual and reproductive rights, same-sex marriage and adoption, new reproductive technologies, sex education, gender mainstreaming, protection against gender violence and others”. The term operates, according to the authors, as an interpretative framework or an empty signifier that would allow different actors, such as politicians, members of religious organizations, anti-abortion associations, and defenders of the traditional family, to organize a reaction to reforms aimed at guaranteeing the rights of women and the LGBTQIA+ population. This definition is close to the argument of Petó (2015), who states that the category gender is used by anti-gender movements as a “symbolic glue”, since it would allow the aggregation of different agendas aimed at the transformation of Western values and politics, such as the language of human rights. This unification of diverse actors and agendas would operate, according to Kuhar and Paternotte (2017, p. 260-1), based on the defense of three “Ns”: nature, nation, and normality.

The anti-gender agenda had already been articulated in Brazil mainly via legislative branch, with a strong religious component (Lacerda, 2016; Machado, 2016, 2017; Luna, 2015; Vital and Lopes, 2013; Mariano, 2018)[3]. From the beginning of the Bolsonaro government, institutional anti-gender activism has strengthened in the executive branch, intensely played by Minister Damares Alves, who enjoys great popularity. The minister has been involved in situations in which references to the anti-gender agenda are mobilized, as in the video filmed on the inauguration day of the Bolsonaro government, in which she says: “Attention, attention. This is a new era in Brazil. Boys wear blue and girls wear pink”. The image and the evoked colors make up one of the transnational symbols of the anti-gender movements. Noteworthy in this context is the change of name of the portfolio responsible for human rights to Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights (MMFDH), which makes explicit the centrality of the family for the current Brazilian government.

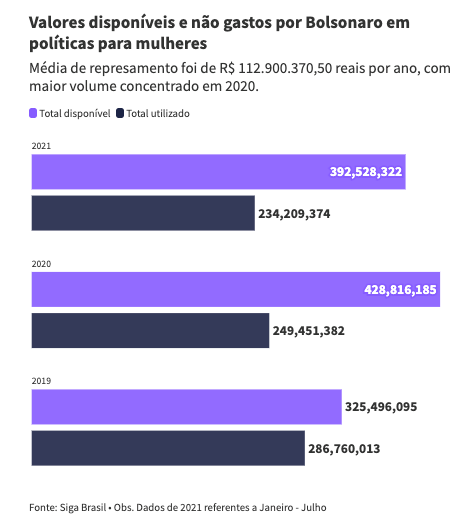

These changes were not merely rhetorical. First of all, there has been a reduction not only in the budget allocated to the portfolio, but also in the amounts spent, that is, in the resources actually spent on public policies, as shown in Graph 2. Thus, even though in nominal terms the budget value of the portfolio has been increased between 2019 and 2021, when we look at the resources spent, they have been decreasing annually, even in a context of greater demand for public policies due to the pandemic. These cuts have greatly weakened the actions aimed at guaranteeing women’s rights in a context of extreme vulnerability, reinforced by class, gender and race[4].

Graph 2: Amounts available and not spent by Bolsonaro in women’s policies

Source: AzMina, 2021.

Moreover, as pointed out by AzMina, in budgetary terms, “the 2016 Program called ‘Policies for Women: Promotion of Equality and Confronting Violence’ ceased to exist and in its place came the ‘5034 Program – Protecting life, strengthening the family, promoting and defending human rights for all’. This change, already signaled in the new name of the ministry, implied in a shift in the focus of policies from women to families, which can contribute to invisibilize intra-family inequalities and violence, since the family to be strengthened in the actions of the Bolsonaro government is the nuclear, heterosexual family, called the “natural family” by anti-gender movements.

The notion of a “natural family” converges the three N’s pointed out by Kuhar and Paternotte (2017), since this specific type of family arrangement would be derived from the natural character of the male and female sexes, which would also be complementary, leading to the heterosexual family also being considered natural, merely derived from human nature and, therefore, normal. This family configuration would be at the basis of the formation of society and would be identified as one of the most important national values, being therefore fundamental to the idea of (and the formation of) the Brazilian nation.

The strengthening of this traditional family model, also marked by the sexual division of labor[5], converges with the advance of the neoliberal reform agenda intensified by the Bolsonaro government, such as budget cuts in social policies, stimulated by Constitutional Amendment 95, which established a ceiling on government spending for 20 years. The retraction of the State’s role in offering social policies ends up putting even more pressure on Brazilian women, who have to give up paid work or even access to formal education to meet family demands related to reproductive work and care[6]. These issues are now considered private matters and should be treated as the responsibility of families and not of the State. In this sense, the government’s rhetoric of strengthening the family has been accompanied, in fact, by public policies that put even more pressure on Brazilian families, especially if we consider the actions aimed at generating employment and income, income redistribution, and food security, just to name a few examples.

Finally, it is important to highlight that this action was not restricted to the domestic sphere, and Brazil, unfortunately and in disagreement with international treaties of which the country is a signatory, has gained international prominence in the anti-gender agenda, as shown by the actions of the MMFDH and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MRE) around the Geneva Consensus. This agreement, which condemns abortion, proposes the defense of the heterosexual family and of national sovereignty (in an articulation that again reinforces the centrality of the three N’s for anti-gender movements), was signed by 36 countries, among which stand out those with the worst performance in terms of guaranteeing women’s human rights and the quality of democracy, such as Poland, Hungary, and Russia, besides Saudi Arabia.

This action converges with other previous international actions, such as the Brazilian government’s opposition to the guarantee of universal access to sexual and reproductive health policies, its abstention during the voting on the UN Human Rights Council’s report on actions against discrimination against women and girls, and the support Brazil gave to a text presented to the OAS that dealt with authorizing parents to impose religious or moral education on their children. With the departure of Chancellor Ernesto Araújo from the MRE, Damares Alves took a leading role in the advancement of conservative agendas on the international scene as well, and Brazil became a kind of “showcase” of the anti-gender agenda for other countries in the world, especially in Latin America, such as Uruguay (Abracinskas et. al., 2020).

These elements point to the centrality of gender relations in the processes of crisis of democracy in Brazil, which means to affirm that they should not be treated as epiphenomena of this crisis or as a “smokescreen” to divert the focus from more central issues in this process of democratic crisis. Gender has assumed, as Kóvatz and Põim (2015) argue, the role of symbolic glue between various conservative, reactionary, and neoconservative movements, allowing the articulation of distinct agendas through the use of moral panic strategies, unifying the defense of family, nation, tradition, normality, and “democracy”, identified (mistakenly, but intentionally) as the interest of the majority[7], in opposition to the demands and agendas of the “minorities of minorities” (feminists and LGBTQIA+ groups). In this sense, understanding the relationship (or the “elective affinities”) between gender (as well as sexuality and race), conservatism, neoliberalism, and populism is urgent if the focus is on reversing the setbacks implemented by the Bolsonaro government and resuming and strengthening democracy in the country.

Notes

[1] This text presents excerpts from previous collaborative/coauthored work. However, the analyses presented in this post are the responsibility of the author. See: Rezende, Brito and Ogando (2019), Rezende, Ávila and Teixeira (2020); Rezende, Elias and Ávila (2021) and Rezende and Sol (2021). Special thanks to Ana Carolina Ogando and Luciana Andrade for their comments on the preliminary version of this post. The Portuguese version is available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358241750_Menino_veste_azul_menina_veste_rosa_Bolsonaro_e_a_agenda_antigenero_como_politica_de_governo_no_Brasil_Versao_em_portugues_do_post_publicado_em_httpspex-networkcomspecial-reports.

[2] Evangelical pastor and former advisor to Magno Malta, former parliamentarian linked to the evangelical caucus.

[3] The virulent reactions to the National Human Rights Plan, the Brazil without Homophobia Program, the recognition of same-sex civil union by the STF, the National Education Plans, the National Plan for the Promotion of Citizenship and LGBT Human Rights stand out as milestones of anti-gender activism in the legislature (Miskolci and Campana, 2017).

[4] In addition, a report published by the National Transvestite and Transgender Association highlights that in 2019, “there has been a 114% increase in the number of murders of transgender people in the country. Data from the NGO Trangender Europe also highlights that Brazil is one of the deadliest countries for trans people in the world.

[5] According to Hirata and Kergoat (2007), the sexual division of labor is based on two principles: separation (of jobs considered feminine from those considered masculine) and hierarchization (since masculine jobs are generally more valued than jobs considered feminine). In the “natural family” model, the sexes are considered complementary and the sexual division of labor would be the result of the natural differences between men and women and not the product of generified social relations.

[6] For analyses on this relationship, see Santos (2019); Biroli et. al (2020).

[7] Already in the 19th century, John Staurt Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville called attention to the risk of “tyranny of the majority” inherent in democracy, whether related to the actions of the State or to public opinion. In this sense, the authors point to the limits of identifying democracy only with the interests of the majority, arguing that there should be safeguards for minority rights, such as freedom of opinion, expression and demonstration, and political participation at the local level.

References

ABRACINSKAS, L.; PUYOL, S.; IGLESIAS, N; KREHER, S. Politicas antigénero en Latinoamérica: Uruguay, el malo exemplo. Montevideo: MYSU, 2019.

ARAGUSUKU, Henrique. A. O percurso histórico da “ideologia de gênero” na Câmara dos Deputados: uma renovação das direitas nas políticas sexuais. Agenda Política, v. 8, n. 1, p. 106-130, 2020.

BIROLI, Flávia; VAGGIONE, Juan Marco; MACHADO, Maria das Dores Campos. Gênero, neoconservadorismo e democracia: disputas e retrocessos na América Latina. Boitempo Editorial, 2020.

HIRATA, Helena; KERGOAT, Danièle. Novas configurações da divisão sexual do trabalho. Cadernos de pesquisa, v. 37, p. 595-609, 2007.

KOVÁTS, Eszter; PÕIM, Maari. (Eds). Gender as symbolic glue: the position and role of conservative and far right parties in the anti-gender mobilizations in Europe. Budapest: FEPS; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015.

KUHAR, R.; PATERNOTTE, D. (Eds.). Anti-gender campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing against equality. Rowman & Littlefield International, 2017.

LACERDA, Marina. B. Ideologia de gênero na Câmara dos Deputados. 10º Encontro Da Associação Brasileira De Ciência Política, 2016.

MACHADO, Maria das Dores C. Pentecostais, sexualidade e família no Congresso Nacional. Horizontes Antropológicos, n. 47, p. 351-380, 2017.

MACHADO, M. das D. C. O discurso cristão sobre a “ideologia de gênero”. Revista Estudos Feministas, v. 26, n. 2, 2018.

MARIANO, Rayani. Conservadorismo na Câmara dos Deputados: discursos sobre “ideologia de gênero” e Escola sem Partido entre 2014 e 2018. Teoria e Cultura, v. 13, n. 2, 2018, p. 118-134.

MISKOLCI, Richard; CAMPANA, Maximiliano. “Ideologia de gênero”: notas para a genealogia de um pânico moral contemporâneo. Sociedade e Estado, vol. 32, núm. 3, 2017, pp. 725-747. Available at: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3399/339954301008.pdf. Acesso em: 16 out. 2019.

PETØ, Andrea. Epílogo: “Anti-gender” mobilizational discourse of conservative and far-right parties as a challenge for progressive politics. In: KOVÁTS, Eszter; PÕIM, Maari. (Eds). Gender as symbolic glue: the position and role of conservative and far right parties in the anti-gender mobilizations in Europe. Budapest: FEPS; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015. Pp. 126-131.

PISCOPO, Jennifer. Inclusive Institutions versus Feminist Advocacy: Women’s Legislative Committees and Caucuses in Latin America. 23o Congresso Mundial de Ciência Política, 2014.

REZENDE, D.; BRITO, M. P.; OGANDO, A. C. Substantive Representation of Women in Brazil in the thirty years of the Constitution. Mimeo. 2019.

REZENDE, Daniela Leandro; ÁVILA, Luciana Beatriz; TEIXEIRA, Camila Olídia. Cidadania religiosa e movimentos antigênero na Câmara dos Deputados brasileira: uma análise dos discursos de legisladores/as, 2014-2017. Contemporânea, v. 10, n. 2, p. 585-612, 2020.

REZENDE, D.; ELIAS, Maria Lígia; ÁVILA, Luciana. B. Gender Ideology in Latin America: Analysis of Legislative Speeches in Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Uruguay. 26o Congresso Mundial de Ciência Política, 2021.

REZENDE, D; SOL, Aruna. “Ideologia de gênero” na produção acadêmica brasileira recente. Teoria e Cultura, v. 16, n. 2, 2021b.

SANTOS, Rayani M. Pensando a família como um dos pontos de intersecção entre o neoliberalismo e o conservadorismo. III Simpósio Pós-Estruturalismo e Teoria Social. Pelotas/UFPel, 2019. Available at: https://wp.ufpel.edu.br/legadolaclau/files/2019/07/ARTIGO-Santos.pdf

VITAL, Cristina.; LOPES, Paulo. V. L. Religião e política: uma análise da atuação de parlamentares evangélicos sobre direitos das mulheres e de LGBTs no Brasil. Fundação Heinrich Böll, 2013.

Share this post: