Ryan E. Carlin, Gregory J. Love and Brenda Mercado

In less than eleven months, Brazilian voters will decide the political fate of President Jair Bolsonaro. Pre-election polling suggests former president Lula da Silva will be his most formidable challenger. These two political foes first clashed in 2018, when a corruption conviction forced Lula to withdraw from the race four weeks before the election. Lula was the frontrunner then, as now. In the coming months, can Bolsonaro garner enough popular support to fend off Lula and earn a second term? Or is it too late?

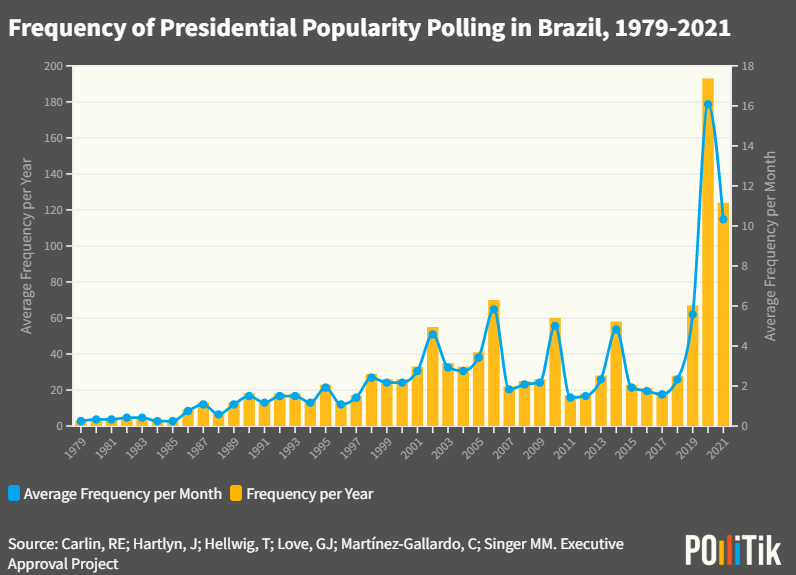

Although we would love to see into the future, we don’t have a crystal ball. But we do possess a strong theoretical foundation on the dynamics of presidential approval to place Jair Bolsonaro’s popularity into national and international contexts. We are aided in this task by a wealth of historical data in Brazil, where polling on presidential approval has exploded in recent years (see figure below), and data from other reference cases in Latin America and beyond from the Executive Approval Project.

A Word or Two on Presidential Approval and Its Dynamics

Presidential approval is a telltale of political power. It indexes executive authority at any given moment (Neustadt 1963) and popular presidents pass more of their agenda (Calvo 2007). Unpopular presidents resort to “going public” to shore up support for their policies (Cockerham et al. 2019) but resist ruling by decree (Shair-Rosenfield and Stoyan 2018). Low approval can be a leading indicator of cabinet (Martinez-Gallardo 2012, 2014) and government instability (Pérez-Liñán 2007). High approval can foretell attempts to alter term limits (Corrales 2018). And presidential popularity is a key parameter in most economic approaches to election forecasting (Belanger and Trotter 2017). Popularity is nearly synonymous with power.

Pioneering work on U.S. presidents discovered presidential approval often obeys a cyclical pattern for each presidency: approval ratings peak when the president is sworn in, erode slowly before bottoming out, only to rise again sometime in the last year of the term (Mueller 1970, Stimson 1976). This pattern consists of three specific dynamics.

First is the “honeymoon.” Elections generate unrealistic hopes of what the new government can do. Not surprisingly, “[e]arly naive expectations lead to later cynicism” (Stimson 1976, 10), forming the second dynamic: a backsliding of approval that reaches a trough somewhere in the last year of the term. This reflects the “costs of ruling” (Wlezien 2017, Nannestad and Paldam 1999). That is, policymaking perpetually creates new “losers,” a portion of whom turn their backs on the president until, ultimately, approval is confined to the president’s most reliable base (Mueller 1970). The third and last dynamic is the campaign/end-of-term bump. Campaigns, staged events, and often electoral budget cycles boost presidential approval (Nordhaus 1975); yet, presidents rarely approach the popularity levels they enjoyed during their honeymoons (Stimson 1976, Brace and Hinckley 1992).

This pattern of cyclical approval extends beyond the United States to Europe (Müller and Louwerse 2020) and Latin America (Carlin et al. 2018), outlier presidents and countries notwithstanding (Mueller 1970; Carlin and Martinez-Gallardo 2019). Do Brazilian presidents exhibit these approval dynamics? If so, then it should inform our expectations vis-à-vis Bolsonaro’s popularity over the coming months and, in turn, his electoral prospects.

Bolsonaro’s Approval Dynamics in Brazilian Perspective

Two criteria guide our selection of presidencies for this comparative analysis of approval dynamics in Brazil. Taking presidential office by the ballot box is the first. Brazilian presidents of the Nova República have gained and lost power via electoral as well as non-electoral pathways. But campaigns and elections truly drive the cyclical pattern, and Bolsonaro himself was popularly elected. This rules out José Sarney, who assumed power after the inaugurated president, Tancredo Neves, took ill and died. It also excludes Itamar Franco and Michel Temer, who ascended to the presidency following impeachments.

Our second criterion restricts comparison to first-term presidents. The basic cyclical pattern may hold in a president’s second term but the dynamics can be distorted — less initial support, shorter honeymoons, greater costs of ruling, and the end of term doesn’t involve a campaign for reelection (see Brace and Hinckley 1992). We, therefore, exclude the second terms of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Lula de Silva, and Dilma Rousseff. This leaves us with the five cases of Collor de Mello, Cardoso, da Silva, Rousseff, and Bolsonaro during their first terms.

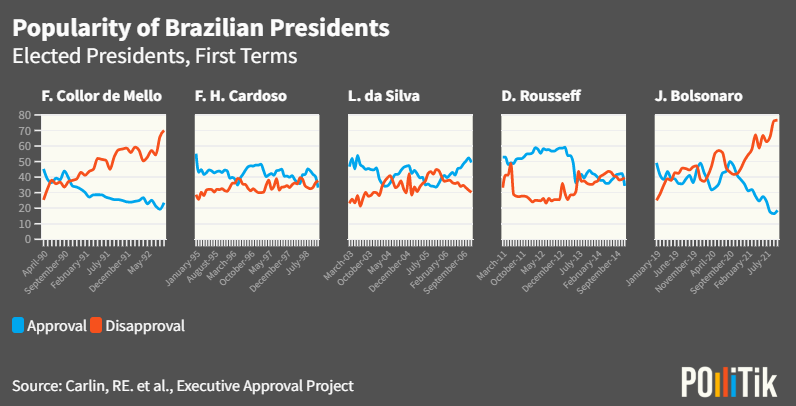

The figure below displays approval and disapproval series for each president as estimated using Stimson’s (1991) dyad-ratio algorithm applied to all available polls housed in the Executive Approval Project. As such, they should be considered best estimates of latent presidential public popularity and unpopularity, respectively. By and large, these five presidencies do not conform terribly well to the classic cyclical model. Yet despite the large variance in how the Brazilian public has evaluated them, each of these leaders displays at least one of the three classic approval dynamics.

Honeymoons

According to Carlin et al. (2018), the average presidential honeymoon period in Latin America lasts about nine months. Bolsonaro enjoyed virtually no honeymoon. On the contrary, his support eroded fairly consistently over his first nine months in office. How does Bolsonaro’s honeymoon compare with that of his four predecessors from inauguration to the end of their third quarter in office?

Except for Dilma Rouseff, popularity peaked during the honeymoon period in each of these first-term presidencies. Jair Bolsonaro’s entering approval (49%) and 10-point drop is in the same ballpark as Fernando Collor de Mello and Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Both lost roughly 11 points in their first three quarters, from 45 to 34 and 55 to 44, respectively. Lula da Silva, however, started with around 47 percent support and did not see his popularity erode until the end of his first year in office. And Dilma Rousseff enjoyed a tremendous honeymoon, her approval rating defying gravity for 27 months and hovering within 6 points of her initial rating (53 percent). In all, Bolsonaro’s honeymoon was decidedly middle-of-the-pack in terms of both incoming support and how quickly it eroded.

Costs of Ruling

Collor de Mello’s modest honeymoon gave way quickly to sinking approval (and spiking disapproval) that ended in his impeachment. Otherwise, these Brazilian presidents contradict the dictum that ruling is costly. Cardoso exhibited by far the most stable levels of approval of any president in our analysis (standard deviation = 3.8). Perhaps this owes to his ability to tame hyperinflation. Lula’s strange dynamics include a decline after his advisor’s, José Dirceu, numbers racket scandal and the slight economic contraction in 2003, followed by a surge in approval linked to strong economic conditions in the following years (Hunter and Power 2005). The mensalão scandal that enveloped Lula’s Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) eventually slowed his momentum. For her part, Rousseff’s extended honeymoon was ended by protests around the Confederations Cup — a warm-up for the World Cup and Olympics mega-events — and a list of social grievances they brought to light (Santos Mundim and Almeida da Silva 2019).

Six months into his term Bolsonaro was paying the costs of ruling right on schedule, with approval in the low-40s to mid-30s. COVID-19 gave him a slight rally-’round-the-flag boost (Yam et al. 2020; cf. Sosa-Villagarcia and Hurtado Lozada 2021). Massive outlays of emergency aid coupled with his supporters’ consumption of friendly online media (Batista Pereira and Nunes 2021), ignorance about the coronavirus, and beliefs in conspiracy theories (Gramacho et al. 2021) likely softened the blow of the pandemic on Bolsonaro’s popularity. But by October 2020, he was losing public support at a quick rate. Indeed, Bolsonaro registered levels of disapproval no popularly-elected has seen since Fernando Collor — including in the throes of Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment. Likely causes include Bolsonaro’s initial denial and outright inaction in the face of COVID followed by his lack of coordination of public health response with (and at times antagonism towards) governors and mayors (Inácio et al. 2021).

The Campaign/End-of-Term Bump

Many presidents leverage campaigns — ads, rallies, partisan mobilization — to bolster their public standing (Stimson 1976; Carlin et al. 2018). Even if the incumbent is not on the ballot, their party’s campaign often centers on the incumbent’s accomplishments. Campaign/end-of-term bumps may also reflect the political-business cycle (Nordhaus 1975). As the election date creeps closer and closer, incumbents may be tempted to increase the monetary supply through fiscal or monetary means. Priming the economy via fiscal policy is difficult to time with the election since working with legislatures can be slow and uncertain, and policy implementation is time-consuming. Monetary policy can be an ideal vehicle for politicians seeking reelection to encourage short-term economic booms (often with substantial longer-term economic consequences). In many countries, this route is now limited by the establishment of independent central banks.

As our figure shows, campaign bumps do not seem to be the norm in Brazil. Collor was impeached before his reelection campaign could get underway. Offsetting any positive campaign effects for Cardoso was a growing economic crisis triggered by successive international economic crises in Mexico (1995), Asia (1997), and Russia (1998) (Ferreira and Naruhik Sakurai 2013). Lula appears to have enjoyed a campaign bump. While Lula’s high popularity certainly reflects robust economic conditions — wage and GDP growth, increased industrial production, low inflation (e.g., Flynn 2005) — it may also reflect his rising “charisma” (Ferreira and Naruhik Sakurai 2013), which the campaign surely heightened. The difficulty of using the political-business cycle in Brazil, both politically and institutionally, for electoral advantage could partially explain why reelection bumps appear to be rare and/or small. Nevertheless, evidence indicates both Cardoso and Lula attempted to raise their support through opportunistic fiscal — but not monetary — policy (Costa, Jr. et al. 2021).

Lack of historical precedent for a vigorous end-of-term bump in Brazil could be a cause for alarm for incumbent Jair Bolsonaro. He enters the 2022 campaign with the lowest approval rating and highest disapproval ratings of any of his successors. Nevertheless, populists excel in campaigns, which allow them to go on the attack against establishment elites (like Lula, his main contender) and, in so doing, cleave society to make the election a majoritarian exercise (Urbinati 2017).

A 2021 law strengthening Central Bank independence should frustrate any attempts by Bolsonaro to manipulate interest rates or the money supply to his advantage. Yet, the president seems to be looking for ways to sidestep monetary and fiscal constraints with a proposed constitutional amendment loosening restrictions on government budgets in a short-term tactic to increase growth and decrease unemployment and poverty ahead of the 2022 election (The Economist 13/11/2021). Thus, while few previous Brazilian presidents have enjoyed substantial reelection bumps, Bolsonaro may be creative enough to raise his approval heading into October.

Presidential Approval and Re-Election Prospects

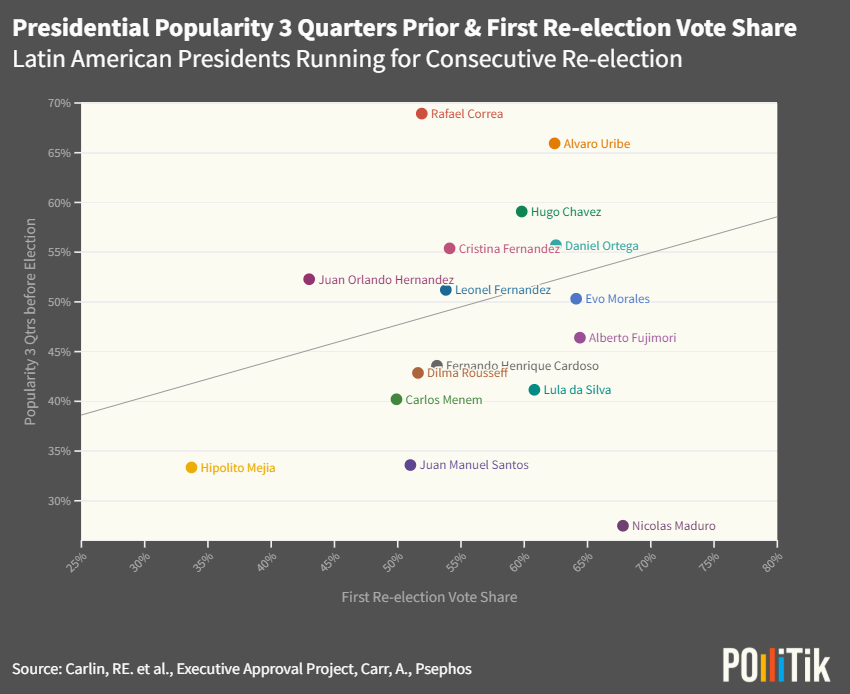

Does Bolsonaro’s popularity have any bearing on his electoral success? To gain some leverage on this question, we compiled data on two reference groups of incumbents seeking their first consecutive reelection: (1) Latin American presidents since 1979 and (2) presidents who have presided over significant declines in liberal democracy in the past three decades. Whether approval ratings correlate with vote shares among either of these groups could shed some initial light on Bolsonaro’s 2022 reelection bid. Of course, most forecasts that rely on approval ratings are unreliable more than 3 months prior to the election. Therefore, this exercise should be taken as illustrative and still quite preliminary.

At first glance, the relationship between incumbent popularity three quarters (9 months) from the election and vote shares is positive but modest (r = 0.235). Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro is clearly an outlier. And it would be reasonable to exclude his first reelection bid given that it took place under, essentially, authoritarian circumstances. The same could be said for Peru’s Alberto Fujimori. If those data points are removed, the correlation more than doubles (r = 0.52). Note that Bolsonaro’s current popularity estimates are in the same ballpark as Maduro’s were at this point. If he follows the trend of democratic presidents, a simple regression suggests he would be expected to receive 51.6% of the second-round vote. If he resorts to more authoritarian electoral strategies or more severely damages liberal institutions in the coming months, Maduro’s example suggests he could win an even greater percentage of the vote.

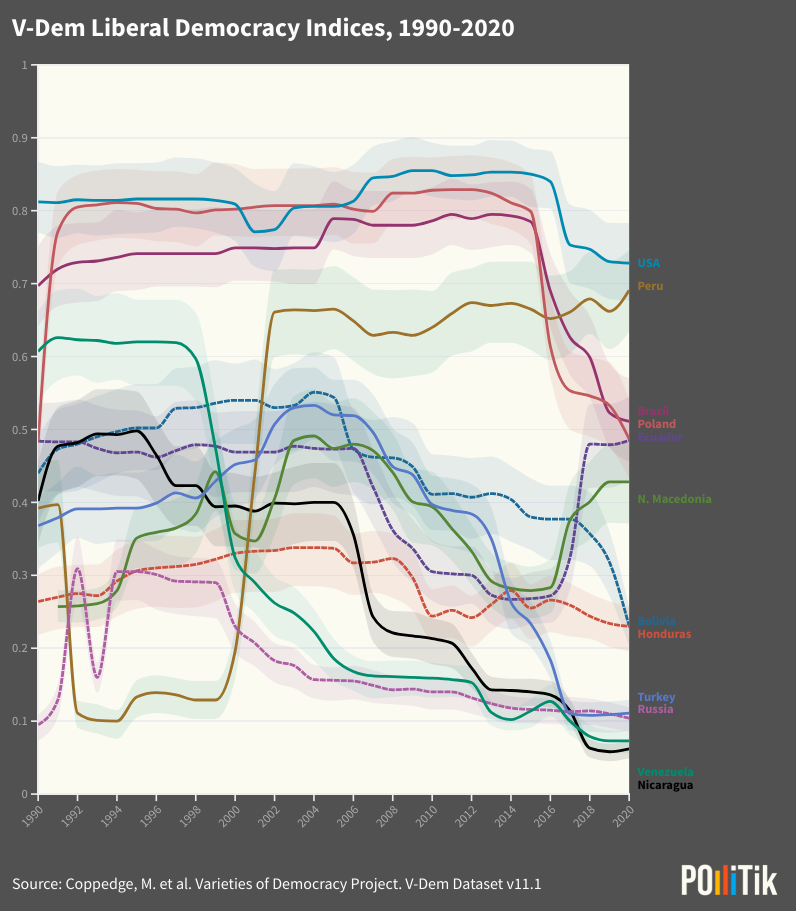

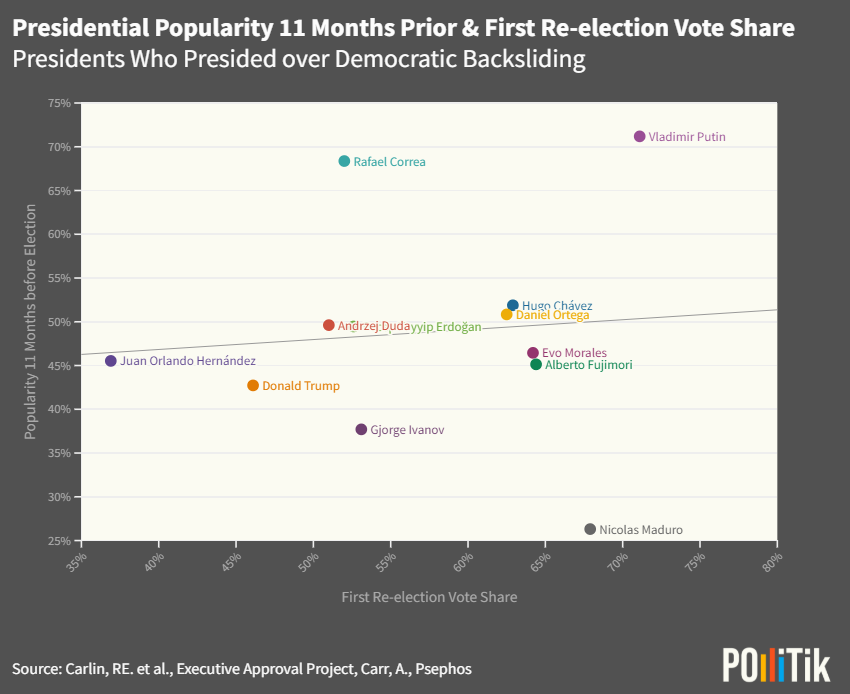

Does approval work differently for aspiring authoritarian leaders when it comes to vote shares? Again, this analysis is preliminary and based on those cases which both exhibited a marked decrease in liberal democracy according to V-Dem and for which the Executive Approval Project has sufficient data 11 months prior to the election. See the figure below.

In this case, the relationship between approval and vote share is far weaker though still positive (r = 0.094). We see a few outliers below (Venezuela’s Maduro and North Macedonia’s Ivanov) and above the line (Ecuador’s Correa and Russia’s Putin). Its overall flatness, however, implies that approval ratings at this point in the election cycle are not terribly indicative of vote shares in these contexts of democratic backsliding. Given the tools at these incumbents’ disposal, and the much stronger association in more democratic contexts observed above, this is no surprise.

Concluding Thoughts

Observers of Brazilian politics and democracy’s champions the world over are closely monitoring Jair Bolsonaro’s reelection bid. Many voters see this as a Catch-22: a choice between a populist with authoritarian tendencies and a committed democrat convicted for corruption. Bolsonaro’s popularity ratings are, we have argued, a critical bellwether for his election prospects. And we have attempted to place his popularity in context. Our analysis leads us to three central conclusions.

First, given his current levels of support, Bolsonaro’s re-election is presently a toss-up. Brazilian history is on his side: no Brazilian incumbent has sought reelection and lost. And our very simple forecast that he will (barely) eclipse 50% in a runoff election. Nevertheless, there are reasons for concern. No presidents in Brazil or his counterparts in Latin America and beyond have entered a reelection campaign with less approval or more disapproval than Bolsonaro has today. Moreover, few incumbents have faced such a strong challenger as Lula in their reelection bids. Our preliminary analysis indicates that Bolsonaro’s reelection will be hard fought without further dismantling democracy’s side rails.

Second, Brazilians would appear to be holding Bolsonaro accountable for policy outcomes. Certainly, the COVID-19 overwhelmed leaders around the world. Bolsonaro, however, downplayed the coronavirus relentlessly, resisted lockdowns, and claimed the economy mattered über alles. Yet as Brazil registers the 10th highest COVID death rate in the world (and second only to Peru in the Americas), his deep unpopularity suggests that many Brazilians have assigned him responsibility for these tragic outcomes along with a sluggish economic recovery and a mounting fiscal crisis. More rigorous analysis is necessary to investigate such hypotheses, but Bolsonaro appears to be reaping what he has sown and democracy functioning as it should.

Third and finally, Bolsonaro’s popularity is not (yet) trending in the right direction. It is still early, of course. Per the cyclical model, most presidents are the least popular at this point in their terms. Unfortunately for Bolsonaro, few Brazilians presidents have managed to boost their approval at the end of their terms using campaigns or cyclical spending. Since the monetary route is increasingly complicated, the fiscal route looks most appealing. Whether or not the new social spending and policies Bolsonaro is preparing will ultimately help him is far from clear.

In closing, we underscore the preliminary nature of our analysis and that any and all conclusions are necessarily tentative. Comparative analysis is an important tool for social scientists, and we have tried to use it appropriately and to draw appropriately bounded conclusions. A more fully-informed forecasting model, however, is necessary in order to grasp the significance of presidential approval for Bolsonaro’s election chances.