André Borges, Mathieu Turgeon, and Adrian Albala

Extant research has often assumed that post-electoral incentives and constraints play a central role in government formation in multiparty presidential systems. According to this interpretation, coalition bargaining only starts after presidential election results are known. Presidents’ coalition-making strategies would depend mostly on factors such as the size of the president’s party in the legislature, the ideological position of the median legislator and the scope of the president’s legislative authority. By definition, all these variables operate in the post-electoral period, when both the identity of the formateur party and the partisan composition of the legislature are known[1].

We argue that this framework offers only a partial and unsatisfying account of cabinet formation in presidential systems because the majoritarian nature of presidential elections creates strong incentives for pre-electoral coalition formation, especially in multiparty settings where no single party can expect to obtain alone a majority of the vote (Samuels, 2002; Spoon and West, 2015){Spoon, 2015 #144}. These electoral incentives carry a direct and important impact on government formation. Indeed, recent research on cabinet formation in presidential regimes has shown that multiparty cabinets frequently originate—partially or totally—from pre-electoral coalitions (Freudenreich, 2016; Albala, 2017 ; Carroll, 2007; Bunker, 2019; Chasquetti, 2008).

Although it has been demonstrated that governments coalition comprised of pre-electoral coalitions (PEC) parties are more likely than not to form, we still know little about the implications of PEC formation for presidents’ disposition to cooperate with legislators and implement their agenda through the negotiation and approval of legislation in the assembly, rather than relying on unilateral constitutional powers. We seek to understand to what extent the formation of PECs increases the likelihood of a president whose party fails to obtain a legislative majority (hereafter minority-party president) in successfully forming a majority coalition cabinet.

Our central claim is that minority-party presidents elected with the support of a multiparty PEC are more likely to succeed in obtaining a legislative majority than a minority-party president supported solely by her co-partisans during the presidential race. Pre-electoral agreements rely on a broader set of rewards than any post-electoral agreement, by including vote and policy concessions during the electoral campaign. In both the pre- and post-electoral bargaining scenarios, the formateur may distribute cabinet portfolios among coalition parties (or promise to do so if the presidential candidate wins the election). But in the PEC scenario, parties have an incentive to agree on rules of portfolio allocation that do not take into account parties’ legislative bargaining power (as in the case of post-electoral bargaining), thus leading to a more proportional distribution of ministerial positions (Carroll, 2007). Because coalition agreements forged before the election are more encompassing and rely on a broader set of rewards, PEC parties tend to be more reliable and cooperative allies. Therefore, (minority-party presidents can more easily obtain majority support in the legislature in the presence of a pre-electoral coalition, avoiding additional and costly post-electoral bargaining rounds.

However, the above-mentioned effects should vary depending on PEC size in the legislature. Minority-party presidents supported by a large PEC should be able to obtain majority legislative support at lower cost because the need for including additional parties to the coalition cabinet in the post-electoral period is reduced. Minority-party presidents supported by a small minority PEC, for their part, will need to engage in a process of coalition enlargement that will usually require renegotiating the pre-electoral agreement and redistributing portfolios among coalition members. This leads us to our second hypothesis: the likelihood of majority coalition formation should increase as the share of PEC seats increases.

The cabinets formed by Brazilian presidents Lula (2003-2006) and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2014) during their first terms provides a nice illustration of the causal mechanisms assumed by our hypotheses. Lula’s PEC controlled, together with his Worker’s Party (PT), only 25% of lower chamber seats and an even smaller share of the Senate. This forced Lula to form an enlarged coalition that included leftist parties defeated in the first round. However, Lula’s inauguration cabinet still fell short of a majority. One year later, he then decided to invite to the cabinet the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party), the second largest party in Congress. The incorporation of the PMDB faced resistance among coalition partners because it meant allocating scarce office resources to a party that had made an alliance with Lula’s rival in the runoff election (José Serra, of the Social Democratic Party). The PMDB also remained deeply divided with regard to supporting the government. In the end, Lula’s coalition was highly unstable, and it remained in minority for about half of the president’s term (Figueiredo, 2007).

Dilma Rousseff was more successful in obtaining majority support in Congress than her predecessor, although both Lula and Rousseff belonged to the same party and faced the very same institutional and political contexts. The main difference between the two presidencies is that Rousseff made a broad pre-electoral agreement that included the PMDB, together with a constellation of small and medium-sized parties. Lula, on the other hand, relied on a mostly post-electoral coalition. Several top PT officials interviewed by Peron (2018) explained that the decision to form a large PEC was explicitly motivated by the goal of obtaining stable majority support in the legislature if Rousseff were elected. Moreover, the distribution of ministerial portfolios was defined before the election and electoral alliances in subnational and national legislative races were thoroughly negotiated. Finally, to secure the loyalty of the largest coalition party (PMDB), the PT offered the vice-presidential ticket together with a promise of increasing its cabinet portfolio shares and some concessions in the making of subnational electoral alliances (Peron, 2018). In the end, Rousseff formed a supermajority coalition mostly comprised of PEC parties that allowed her to easily pass legislation in Congress during her first mandate.

In sum, comparison between the Lula (2003-2006) and Roussef (2011-2014) presidencies demonstrates the importance of political rewards disbursed during the pre-electoral stage for cementing political coalitions and more easily obtaining majority support.

To test our hypotheses, we use an original dataset of coalition cabinets, originated at the pre- and/or post-electoral stages, from 18 Latin American countries. We built on replication datasets from Kellam (2015) and Meirelles (2016)to obtain information on variables of interest, including those about the partisan composition of presidential cabinets. We also rely on several other sources to learn about the partisan composition of PECs that supported elected presidents and the number of seats held by both the (victorious) pre-electoral and post-electoral coalitions.[2]

Methods and Results

We rely on multivariate regressions to evaluate H1 and H2, controlling for other known determinants of presidents’ ability to form majority cabinets, picked from the existing literature. Our dependent variable is dichotomous and takes the value of 1 for majority cabinets in the lower chamber and 0 otherwise. We label this variable as Majority Cabinet. To test H1, we regress our dependent variable Majority Cabinet on another dichotomous variable (labeled PEC) that takes the value of 1 for all presidents supported by a PEC (model 1). To test H2, we rely instead on a continuous measure of the percentage of lower chamber seats controlled by the PEC parties minus the percentage of seats from the president’s party (model 2). We label this variable as PEC size. Minority-party presidents that did not form a pre-electoral coalition score zero on that variable. All regressions control for the president’s party size and, thus, models estimate the effect of the PEC dummy and the quantitative measure of PEC size while maintaining constant the size of the president’s legislative delegation.

The regression models also include a set of controls that are known to have an impact on the dependent variable. These include veto powers, ideological distance between the president’s party and the mean ideological position of the legislature, party system polarization and a measure of the relative importance of clientelistic linkages for parties’ strategies (obtained from the V-Dem dataset) (Alemán and Tsebelis, 2011; Amorim Neto, 2006; Shugart and Carey, 1992; Kellam, 2015). To deal with intra-cluster correlation and panel heteroscedasticity we rely on GEE and mixed-effects models.

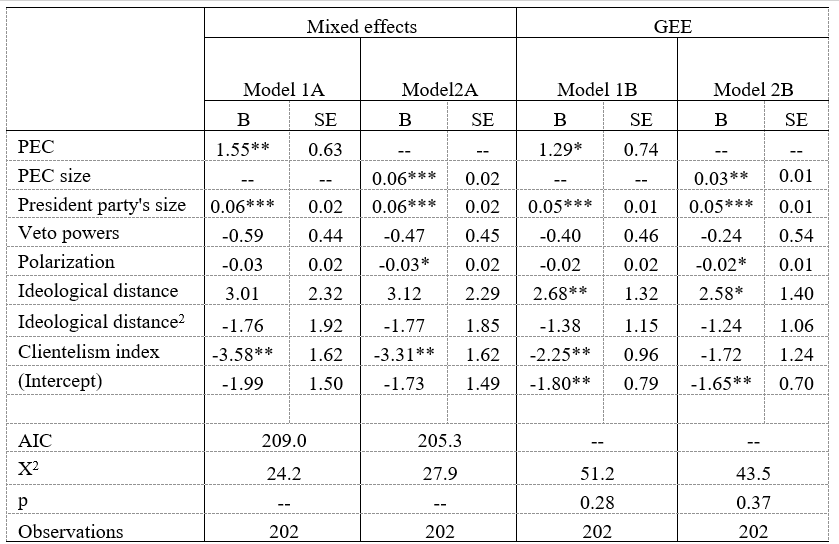

Table 1 presents two sets of regression estimates. Models 1A and 1B utilize one with the dichotomous variable PEC , whereas models 2A and 2B rely on continuous measure of PEC size.

Table 1: Explaining majority cabinet formation

* p<.10; ** p<.05; *** p<.01 (two-tailed)

Source: Borges et al (2020)

When all other variables are set at their means, we find that minority-party presidents with a PEC have a probability of .41 of forming a majority cabinet (GEE model). The probability estimated for model 1A (mixed effects) is even higher at .43. The difference in the probability of forming a majority cabinet between minority-party presidents supported and unsupported by a PEC is .23 and statistically significant (p<.01, two-tailed) for the mixed effects model. The estimated difference using the GEE specification is similarly large at .25, although this result fails to achieve standard levels of statistical significance.

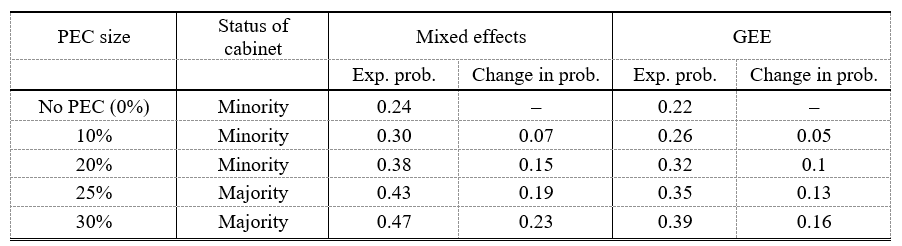

We have also simulated the effect of PEC size on the odds of majority coalition formation while keeping the size of the president’s legislative contingent at its mean value (27%) using the R statistics Zelig package. As shown in table 2 below, having the support of a small PEC controlling 10% of lower chamber seats increases the probability of a minority-party president succeeding in forming a majority cabinet, as compared to a minority-party president without a PEC, by 7 and 5 percentage points for the mixed effects and GEE models, respectively. For a large PEC controlling 30% of the seats, however, we find that the minority-party president’s probability of forming a majority cabinet is 23 percentage points higher than that estimated for a minority-party president unsupported by a PEC (when considering the mixed effects model).

Table 2: Expected probability and change in probability of forming a majority cabinet according to the size of the pre-electoral coalition

Source: Borges et al (2020)†All changes in the probability of forming a majority cabinet from a situation where the minority-party president has no PEC are significant at .05 (two-tailed).

Conclusion

Our results show that pre-electoral bargaining facilitates cabinet agreements, thus making an important contribution to research on coalitional presidentialism. When PECs control a substantial share of legislative seats, presidents will rely to a much lesser extent on the support of legislative parties outside the PEC, thus obtaining a majority cabinet at much lower costs. Consistent with these theoretical expectations, we find that minority presidents supported by very small pre-electoral coalitions are only marginally more likely to form a majority cabinet then presidents elected on the sole support of their co-partisans, whereas these differences are much more substantial for large PECs.

Our findings further suggest that incentives for coordination at the pre-electoral stage are very important predictors of presidents’ policy-making strategies. To the extent that minority-party presidents supported by a large PEC can more easily obtain majority support in the legislature, it is less likely that they will resort to unilateral governing strategies. Thus, one should expect the likelihood of interbranch conflict to be lower in the presence of strong incentives to form pre-electoral coalitions. Future research should explore these sorts of questions, moving beyond the analysis of presidential legislative powers, ideological polarization in the legislature and other post-electoral factors.

Bibliography:

Albala A. (2017) Coalition Presidentialism in Bicameral Congresses: How does the Control of a Bicameral Majority Affect Coalition Survival? Brazilian Political Science Review 11: 1-27.

Alemán E and Tsebelis G. (2011) Political parties and government coalitions in the Americas. Journal of Politics in Latin America 3: 3-28.

Amorim Neto O. (2006) The Presidential Calculus: Executive Policy Making and Cabinet Formation in the Americas. Comparative Political Studies 39: 415-440.

Borges A, Turgeon M and Albala A. (2020) Electoral Incentives to Coalition Formation in Multiparty Presidential Systems. Prepublished, online first version. Party Politics.

Bunker K. (2019) Why do parties cooperate in presidentialism? Electoral and government coalition formation in Latin America. Revista de Estudios Políticos 186: 171-199.

Carroll RA. (2007) The Electoral Origins of Governing Coalitions. Department of Political Science, UCSD, Ph.D. Diss. . UC San Diego.

Chasquetti D. (2008) Democracia, presidencialismo y partidos políticos en América Latina: evaluando la” difícil combinación”: Ediciones Cauce-CSIC / Inst. de Ciencia Política – UDELAR.

Figueiredo A. (2007) Government Coalitions in Brazilian Democracy. Brazilian Political Science Review 1: 182-216.

Freudenreich J. (2016) The Formation of Cabinet Coalitions in Presidential Systems. Latin American Politics and Society 58: 80-102.

Kellam M. (2015) Parties for hire: How particularistic parties influence presidents’ governing strategies. Party Politics 21: 515-526.

Meireles F. (2016) Oversized Government Coalitions in Latin America. Brazilian Political Science Review 10: 1-31.

Peron I. (2018) O Momento de Formação das Coligações e a influência na Formação das Coalizões: um estudo de caso. M.A. Dissertation. Institute of Political Science, University of Brasília, Brazil.

Samuels D. (2002) Presidentialized Parties: The separation of powers and party organization and behavior. Comparative Political Studies 35: 461-483.

Shugart M and Carey JM. (1992) Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional design and electoral dynamics, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Spoon J-J and West KJ. (2015) Alone or together? How institutions affect party entry in presidential elections in Europe and South America. Party Politics 21: 393-403.

[1] When presidential and legislative elections are concurrent, the partisan composition of the legislature is unknown before the elections. However, even when elections do not concur, political actors cannot know for sure which party will form the government, as in presidential systems the winner of the presidential race is always and necessarily the formateur party.

[2] Other sources of data are the Political Database of the Americas (http://pdba.georgetown.edu/), Adam Carr’s Election Database (http://psephos.adamcarr.net), the IPU Parline Database (http://www.ipu.org/parline-e/parlinesearch.asp), and electoral results reported by the countries’ official electoral bodies.