Alexandra Artiles, Martin Gandur and Amanda Driscoll

-

Introduction

On March 6, 2020, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear declared a state of emergency in response to the novel coronavirus, and would issue a stay-at-home order before the end of the month. Governor Bill Lee of neighboring Tennessee would enact the same emergency declarations and stay-at-home orders, albeit roughly a week after Governor Beshear. Both governors took early actions to `slow the spread,’ but the similarities in the governors’ responses end there. The number of days Kentucky businesses were closed was nearly twice (66 days) that of Tennessee (34 days). Come July, Governor Beshear would mandate the use of face-coverings, while Governor Lee would make no similar state-wide requirement, leaving the decision to do so to county and local officials.

Kentucky and Tennessee are nearly equal in terms of ethnic composition, income, and population . Yet, the two governors’ approaches led to dramatically different public health outcomes.[1] The July 31st statewide COVID-19 incident rate in Kentucky was less than half of that (45%) of Tennessee. Beyond health outcomes, Tennessee has experienced higher rates of unemployment, hospitalization, and mortality than Kentucky as a result of the coronavirus pandemic (CDC 2020a).

These discrepancies are emblematic of the tradeoff of U.S. federalism in the time of COVID-19: federal devolution permits state governments maximal flexibility to localize policy as needed, yet state responses and crisis mitigation are distributed unequally across the states (Petersen 1995). We review here the myriad of ways that federalism has shaped the governmental response to the dual health and economic crises brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. We describe the federal government’s decentralized response, and chart states’ efforts at crisis mitigation. We suggest that the limited federal response to the crisis, and the intentional devolution to the states, reverses a century long trend of policy centralization in the hands of the federal government (Artiles et al. 2020).[2]

-

Federalism in the U.S.: The 20th Century Expansion of Federal Power

Since the 1930s, the U.S. has witnessed slow but continual centralization across the vast most policy domains. President D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ administration marked the first phase of centralization, when the federal government expanded with the aim of providing economic relief to millions left in ruin by the Great Depression. The New Deal created social safety net programs that sought to combat homelessness, rural poverty, nationalized unemployment, and provide universal social security. This coordinated federal relief was simply beyond the capacity of any one state to unilaterally provide (Kincaid 2018).

The second phase of federal centralization began in the 1960s, under President Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ program, a sweeping political agenda that aimed to address long-institutionalized patterns of racism and racial segregation, eradicate poverty, reduce crime, abolish inequality, and improve the environment. Medicare and Medicaid were established at this time, providing healthcare to millions, while other federal programs targeted elderly and youth constituencies. These two periods of dramatic federal power expansion over the course of the 20th century imply the federal government’s reach now extends far beyond its narrow constitutional prerogatives.

-

The Much-Less United States?: Federalism in an Era of COVID-19

The federal response to the crises brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic stands as a dramatic about-face to the century-long trend towards federal government empowerment. The federal government’s initial reaction to the looming pandemic crisis was disjointed and at times contradictory, a response that stood in stark contrast to the strong and highly coordinated federal responses crises had elicited in decades past. The first known case of COVID-19 in the United States was diagnosed on January 21, 2020, when a U.S. citizen returned from travel to mainland China. By the end of January, it was confirmed that the virus could be transmitted from person-to-person, implying a likelihood for community spread. One prominent White House liaison predicted that COVID-19 “could infect as many as 100 million Americans, with a loss of life for as many as 1-2 million souls” (Schwellenbach 2020). Yet at the same time, President Trump confidently asserted the contrary, stating that “we have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. It’s going to be just fine,” (Schwellenbach 2020). On February 9, the White House Coronavirus Task Force met with governors to discuss the pandemic, which Maryland Governor Larry Hogan later described in jarring terms: “when I left that briefing…we knew this was going to be a serious crisis” (Schwellenbach 2020).

Most of the subsequent major federal actions would be taken by the end of March. On March 2, Vice President Pence declared that “mitigation, not containment,” was the new goal, a goal that would be abandoned by mid-October (Schwellenbach 2020). The federal government purchased 500 million N95 respirators, and President Trump signed an $8.3 billion emergency response bill on March 6, 2020. One week later, Congress passed The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, creating paid sick leave for COVID-19 related absences, establishing free COVID-19 testing centers, and expanding unemployment benefits. In March’s final days, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provided $100 million to hospitals to care for COVID-19 patients, and the Senate passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, the largest economic aid package in U.S. history (Schwellenbach 2020).

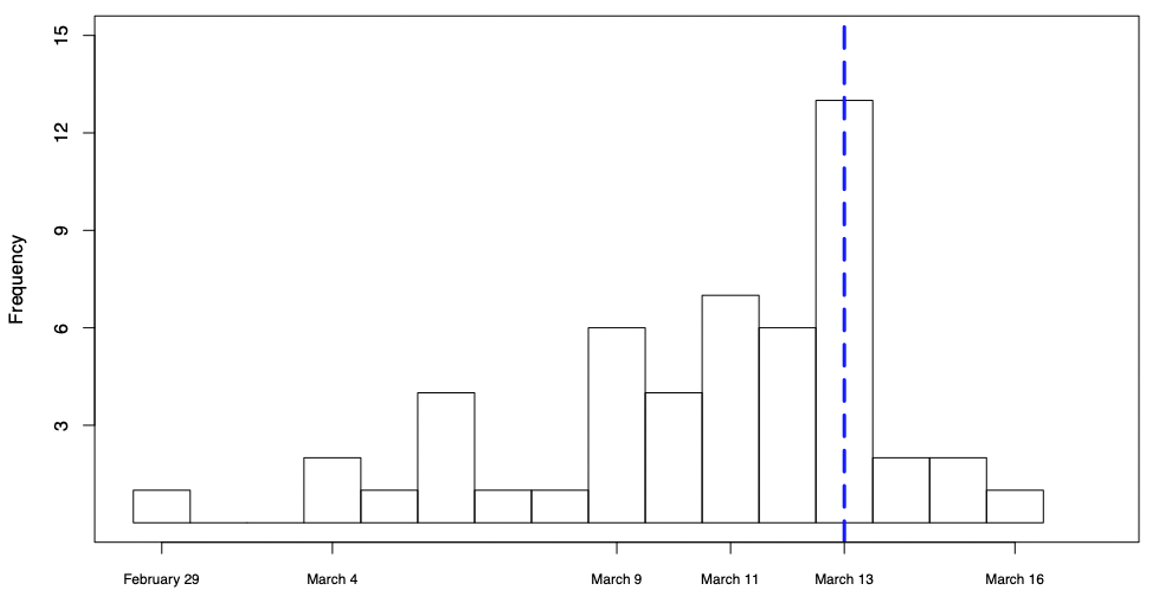

In spite of this historic mobilization of resources, the White House continued to downplay the pandemic, and stalled the declaration of a state of emergency. Figure 1 shows a time-line of states’ emergency declarations, with the dotted line indicating the date on which the federal government issued its emergency declaration, on March 13th, 2020. Washington State was the first to issue a state of emergency on February 29th, followed by California and Hawai’i on March 4th. By the following Monday, an additional 13 states declared state-wide emergencies, such that 5 days prior to the federal emergency declaration, a near-absolute majority (49.55%) of Americans resided in states where emergencies had been declared (Coleman 2020).

Figure 1. States’ Emergency Declarations Preceding Federal Declaration

Figure 1 makes clear that a plurality of states’ (13) emergency declarations coincided with that of the federal government. Although President Trump’s declaration retroactively declared the emergency (and subsequent order) to have been in effect from March 1, 2020, critics claim that, had the federal government made this declaration sooner, Americans would have taken the threat more seriously (Hsiang et. al 2020). By the end of March, nearly every state had an emergency declaration in place, with most issuing stay-at-home orders, while also closing businesses and schools. President Trump openly opposed these state-level shutdowns, saying that he would “love to have the country opened up and just raring to go by Easter” (Schwellenbach 2020).

Yet another foible was the federal government’s approach to testing: although the World Health Organization (WHO) sent hundreds of thousands of tests to the U.S., the Trump administration opted to rely exclusively on tests developed by its own Center for Disease Control (CDC). It was later revealed that many of the CDC tests contained a faulty reagent, preventing many labs from proceeding with testing (Cohen 2020). Consequentially, the U.S. continued to report artificially low case numbers throughout February (Schwellenbach 2020), and further enabled the belief that the pandemic was not a serious public health threat (Cohen 2020). President Trump would privately acknowledge COVID-19 as “more deadly than even your strenuous flus,” all while publicly downplaying the seriousness of the looming global pandemic (Glasser 2020).

State governments quickly became pivotal in managing the health and economic crises, with the President telling governors “you’re going to call your own shots” (Liptak et al. 2020). Although some governors quickly took to the reins of crisis management, others decried the federal government’s approach to be a dereliction of federal duty, and—worse yet, a political move by President Trump to avoid electoral responsibility for pandemic related hardship (Cook and Diamond 2020). Former Maryland governor O’Malley described: “[This] is a Darwinian approach to federalism; [it] is states’ rights taken to a deadly extreme” (Cook and Diamond 2020).

3.2. The States Take Charge

How did states respond to the public health crisis, and what did they do with their newfound authority? We summarize data compiled by the COVID-19 US State Policy Database (Raifman et al. 2020), that chronicles measures taken by states to respond to the twin health and economic crises spurred by the pandemic. We then compare COVID-19 incident rate (infections per 100,000 people) across states as of July 31st (Johns Hopkins CSSE COVID-19, 2020), and find great variation between states’ responses. We suggest some of this variance can be explained with reference to population density: with early COVID-19 outbreaks constrained to the costal urban centers, sparsely populated interior states did not face the same pressure to impose restrictive measures.[3] Yet a clear political pattern to states’ policies is also evident: while states that adopted restrictions were governed by leaders of both major parties, Republican affiliated governors tended to impose far fewer COVID-19 related restrictions.

As described above, all states, territories and several major cities declared formal states of emergency, allowing executives to mobilize resources to combat the coronavirus. A related policy, taken up by thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia (DC) were ‘stay-at-home’ or ‘shelter-in-place’ orders, which discouraged residents from leaving their homes for any reasons other than doctors’ visits, grocery store or pharmaceutical shopping. This would coincide with the mandated closure of restaurants, bars, and non-essential retail operations in 49 states and the District of Colombia.

The shuttering of the world’s largest economy brought with it an unprecedented economic collapse that eclipsed previous crises by orders of magnitudes (Kiefer 2020). With the help of the federal stimulus package, the states became the conduit for relief provisions and support for millions of newly unemployed Americans. Only five states declined to provide some sort of eviction relief—either by suspending judicial proceedings or formally loosening enforcement mechanisms. Thirty-four states prohibited shutting off utilities or gas to homes for COVID-19 related claims. Finally, there was an across-the-board expansion of social safety net investment by the states: every state (and DC) increased access to food security programs and healthcare for lower-income families (Medicare), and many also loosened restrictions for extended access to unemployment benefits.[4]

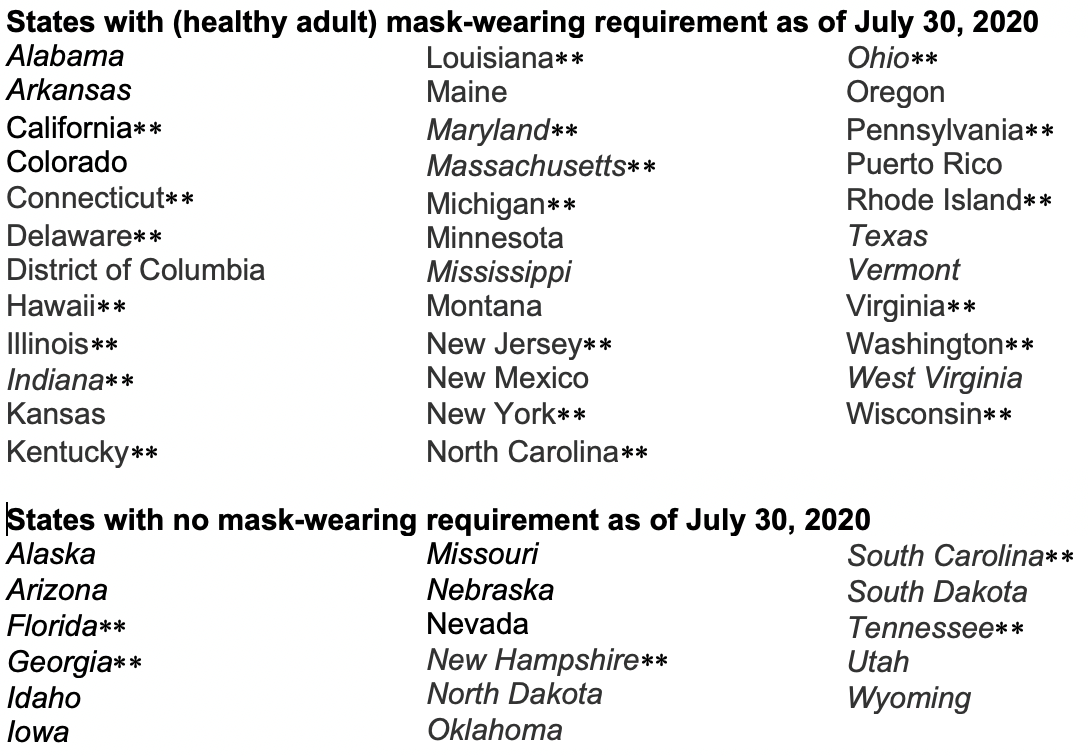

One viral mitigation policy that spurred intense political debate was mandatory mask-wearing requirements, which we show in Figure 2. Although the CDC advised that masks are effective in mitigating the viral spread in early April (CDC.gov 2020b), mask mandates were quickly politicized, with adherents and opposition coinciding neatly with partisan affiliation (Pew Research Center 2020). Opponents to mask-wearing ordinances claim that these measures are an unconstitutional restriction on freedom, and President Trump expressed ambivalence: “you can do it. You don’t have to do it. I am choosing not to do it. It may be good. It is only a recommendation” (Lizza and Lippman 2020). Again, this complacency further undermined state and local governmental efforts to normalize mask-wearing, and publicly disincentivized compliance with mask-wearing rules.

Figure 2. Mask Mandates by State

Italicized state names Republican governors. **Denotes states above the median of population density. Puerto Rico and Washington DC are unranked by population density.

As shown in Figure 2, an absolute majority of states and territories adopted mask mandates. The role of population density is an evident factor at play: sparsely populated states such as Alaska and Wyoming declined to impose restrictive mask-wearing rules, whereas densely populated states (Hawaii) and states of major metropolitan areas (New York) imposed some of the strictest measures. Yet a clear pattern of partisanship also emerges, reflecting the politicized nature of the mask-wearing recommendations. Of the twenty-six states with Republican governors, only 38% (10) would adopt statewide mandates for mask wearing; amongst non-Republican states and territories, 96% of them required masks. Indeed, of the 17 states that declined to adopt a mask-wearing requirement, only Nevada was led by a Democratic governor.

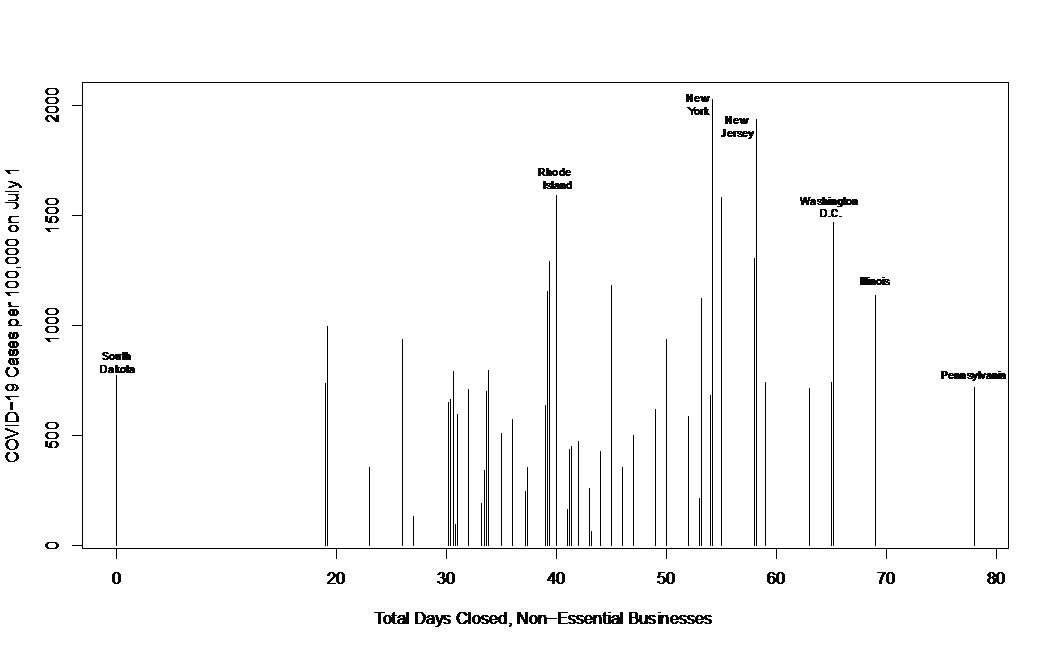

We now examine one possible measure of effectiveness of COVID-19 restrictions to consider the closure of non-essential businesses across states (see Figure 3).[5] The x-axis represents non-essential business closures in days, while the y-axis represents the number of state reported COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people on July 1 (Johns Hopkins CSSE COVID-19 2020).[6] Non-essential business closures ranged from twenty to eighty days. An exception is South Dakota, which never officially closed. States with the lowest case counts are Hawaii, Montana, and Alaska, whose businesses were closed for 43, 30, and 27 days, respectively. States with the highest case rates include Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C. With the exception of California, Florida, and Massachusetts, these states are home to some of the largest – and most densely populated – urban centers.

Figure 3. COVID-19 Cases Per 100K on July 1, by Days of Non-Essential Business Closure

There are several interesting trends of note from Figure 3. First, the bivariate relationship between non-essential business closure and case count shows a modest, albeit positive correlation (r = 0.25). This implies that those states that were shut down the longest also saw the highest rates of infection come July 1. This is unsurprising given the states with the longest duration of shutdowns are also those with major urban centers. Relatedly, the correlation between population density and case count is a positive, but still modest, r=0.35. Finally, when we remove the ten greatest outlier states from our data, the correlation is r=-0.09, which is statistically indifferentiable from zero. This correlation would imply that for the 40 ‘typical’ states, longer shutdowns may have yielded a reduction in the infection rate. This is only conjecture, and if it were true the effect would be minor.

Critically however, with only bivariate correlations, we cannot draw causal conclusions, and the weak correlations we do find demand even more inferential restraint. We do not control for confounding variables, including those that would be critical in explaining incident rates, such as population density (which impacts transmissibility) or breadth and accuracy of testing (which impacts detection). These caveats aside, the relatively weak nature of our correlations point to two potential conclusions. First, whereas the states that closed the longest are also home to populations where transmission was more readily spread (due to high population density), then our weak correlations might indicate the successful mitigation of COVID-19: in these densely populated states and areas, case counts could have been far worse were it not for the state mandates to limit public interaction.[7] Second, our weak correlations might suggest that the states are too diverse to adopt a standardized approach to non-essential business closures and related mitigation strategies. Future research will no doubt interrogate these possibilities in more depth.

-

Conclusion

Our case study of the ‘ever so less’ United States illustrates the intrinsic tensions federalism implies. The pandemic related crises have given states an opportunity to enhance their expertise and innovation through the policymaking process. States have also been empowered to tailor their policies to regionalized – or localized – needs, and deftly shift course when local exigencies required a change. However, this decentralization in times of crisis also illustrates the “price of federalism,” with states offering their citizens very different solutions to the COVID-19 crises, worsening many economic and racial inequalities that predated the pandemic era (Petersen 1995). In other words, the way political leaders approach federalism in times of crises has critical consequences on citizen’s life. The coronavirus pandemic in the US illustrates this point, where hundreds of thousands lives depend on decisions to centralize or delegate power. Future research should continue to scrutinize these trends, to better understand the trade-offs that federalism necessarily entails, and how the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped American federalism in the years to come.

Achenbach, Joel, and Laura Meckler. 2020. “Shutdowns prevented 60 million coronavirus infections in the U.S., study finds.” Washington Post. June 8, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/06/08/shutdowns-prevented-60-million-coronavirus-infections-us-study-finds/. [Accessed 11 November]

Artiles, Alexandra, Martin Gandur, and Amanda Driscoll. 2020. “The (Less) United States: Federalism & Decentralization in the Era of COVID-19.” In Federalism in Times of COVID- 19: A Comparative Perspective, ed, Esteban Nader. Washington, DC: Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020a. “Cases in the U.S.” CDC.gov, 9 October, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020b.“Mask Wearing Evaluation.” CDC.gov, 18 August, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/mask-evaluation.html. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Cohen, John. 2020. “The United States badly bungled coronavirus testing – but things may soon improve.” ScienceMag.org, 28 February, 2020. Available at https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/united-states-badly-bungled-coronavirus-testing-things-may-soon-improve. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Coleman, Justine. 2020. “All 50 States Under Disaster Declaration for the First Time in US History.” The Hill, 12 April, 2020. Available at https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/public-global-health/492433-all-50-states-under-disaster-declaration-for-first. [Accessed 4 October]

Cook, Nancy and Dan Diamond. 2020. “ ‘A Darwinian Approach to Federalism’: states confront new reality under Trump,” Politico.com, 31 March, 2020. Available at https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/31/governors-trump-coronavirus-156875. [Accessed 24 September 2020]

Glasser, Susan B. 2020. “Bob Woodward Finally Got Trump to Tell the Truth About COVID-19.” NewYorker.com, 11 September, 2020. Available at https://www.newyorker.com/news/letter-from-trumps-washington/bob-woodward-finally-got-trump-to-tell-the-truth-about-covid-19. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Hsiang, Solomon, Daniel Allen, Sébastien Annan-Phan, Kendon Bell, Ian Bolliger, Trinetta Chong, Hannah Druckenmiller, Luna Yue Huang, Andrew Hultgren, Emma Krasovich, Peiley Lau, Jaecheol Lee, Esther Rolf, Jeanette Tseng & Tiffany Wu. 2020. “The Effect of Large-Scale Anti-Contagion Policies on the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Nature. 8 June, 2020. Available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2404-8.[Accessed 3 November].

Ingraham, Christopher. 2020. “A Powerful Argument for Wearing a Mask, in Visual Form,” The Washington Post, 23 October, 2020. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/10/23/pandemic-data-chart-masks/. [Accessed 24 October].

Johns Hopkins University. 2020. COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins University. Available at https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19. [Accessed 15 September]

Kiefer, Len. 2020. “US Labor Market Update: The U.S. Labor Market Turns Down.” Len Keifer: Helping People Understand the Economy, Housing and Mortgage Markets. 4 April, 2020. Available at http://lenkiefer.com/2020/04/03/us-labor-market-update-april-2020/. [Accessed 9 October]

Kincaid, John. 2018. “Dynamic De/Centralization in the United States: 1790-2010.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 49(1): 166-193.

Liptak, Kevin, Kristen Holmes, and Ryan Nobles. 2020. “Trump completes reversal, telling governors ‘you are going to call your own shots’ and distributes new guidelines.” CNN.com, 16 April, 2020. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/16/politics/donald-trump-reopening-guidelines-coronavirus/index.html. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Lizza, Ryan and Daniel Lippman. 2020. “Wearing a mask is for smug liberals. Refusing to is for reckless Republicans.” Politico.com, 1 May, 2020. Available at https://www.politico.com/news/2020/05/01/masks-politics-coronavirus-227765. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Pew Research Center. 2020. “Republicans, Democrats Move Even Further Apart in Coronavirus Concerns.” Pewresearch.org, 25 June, 2020. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/06/25/republicans-democrats-move-even-further-apart-in-coronavirus-concerns/. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Raifman, Julia and Kristen Nocka, David Johnes, Jacob Bor, Sarah Lipson, Jonathan Jay, Megan Cole, Noa Krawczyk, Philip Chan, Sandro Galea. 2020. COVID-19 US State Policy Database. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2020-9-15. https://doi.org/10.3886/E119446V30

Schwellenbach, Nick. 2020. “The First 100 Days of the U.S. Government’s COVID-19 Response.” www.pogo.org, 6 May, 2020. Available at https://www.pogo.org/analysis/2020/05/the-first-100-days-of-the-u-s-governments-covid-19-response/. [Accessed 9 October 2020]

Wamsley, Laurel. 2020. “Gov. Says Florida’s Unemployment System Was Designed to Create ‘Pointless Roadblocks’”, National Public Radio (NPR.com), 6 August 2020. Available at https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/08/06/899893368/gov-says-floridas-unemployment-system-was-designed-to-create-pointless-roadblock. [Accessed 3 October]

[1] Consider Simpson County Kentucky, and Robertson County, Tennessee, who share a border along the state line. As of July 31, Simpson County reported 236 cases and 7 deaths, while Robertson County had 8 times as many cases (1,942) and four times the number of deaths (29) (CDC 2020a).

[2] For a more in-depth review, please see our full article, available at https://bit.ly/3l5jqkL.

[3] The tide has since turned. As of October 2020, states with the highest rate of COVID-19 cases are those sparsely populated in the Midwest, including North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska, with the incident rates far exceeding the rates witnessed in COVID-19 hotspots throughout the summer (New York Times 2020).

[4] This is not to say all efforts were effective. One high profile failure played out in Florida, whose faulty unemployment website was so prone to malfunction that by April 20 only 6% of applicants had received benefits. It was later revealed this malfunction was intentional: reforms of the online system under former Governor Scott were designed to make it difficult to apply for benefits, such that the incumbent could report low unemployment numbers during his administration (Wamsley 2020).

[5] We consider the closure of non-essential businesses because the timing and length of time the states imposed this policy varies considerably across the states. Our conclusions are unchanged if we instead use bar and restaurant closures. Please see Raifman et al, (2020) for alternative measures.

[6] Whereas most states moved to shut down non-essential businesses the end of March and the first few days of April, July 1 represents the COVID-19 infection rate roughly three months after these measures were adopted. This is also approximately three weeks after the last state (Pennsylvania) lifted the prohibition, on June 5, 2020.

[7] For instance, researchers estimate that large-scale anti-contagion policies have prevented 60 million COVID-19 infections in the U.S. (Hsiang et. al 2020). See also Achenbach and Meckler (2020), and Ingraham (2020).