Javier Corrales and Philip Corbo

The Pandemic has demonstrated that a terrible underlying condition making democracies vulnerable to the worse effects of the virus is populism and polarization.

The pandemic has tested not just the world’s health systems, but also, its political systems. The virus has spread indiscriminately across democracies and dictatorships. In doing so, it has exposed the best and worst of each type of regime.

In dealing with crises, democracies used to have an advantage – abundance of information. Until they began to suffer the ravages of populism, polarization, and democratic backsliding.

Economist Amartya Sen became famous for his argument that the reason democracies are preferable to autocracies is that they oversupply information. In democracies, communities have mechanisms to communicate their needs to politicians, politicians can count on diverse information to help them deliberate, and voters can use information during elections to punish unresponsive politicians.

But in the era of populism, polarization, and democratic backsliding, this informational advantage has eroded. That is because populist presidents, capitalizing on popular resentment against technical experts, tend to overplay their mistrust of technical expertise, the media, public debate, and inconvenient information. In moments of health crisis, where adherence to information and technical expertise is paramount, these regimes underperform in relation to all the others.

A recent paper on Australia’s response offers a typology of possible responses: autocratic opportunists, fanatists, effective rationalists, and constrained rationalists.[1] The Americas provide examples of each of these categories. And the evidence is that the fanatists offer the worst response.

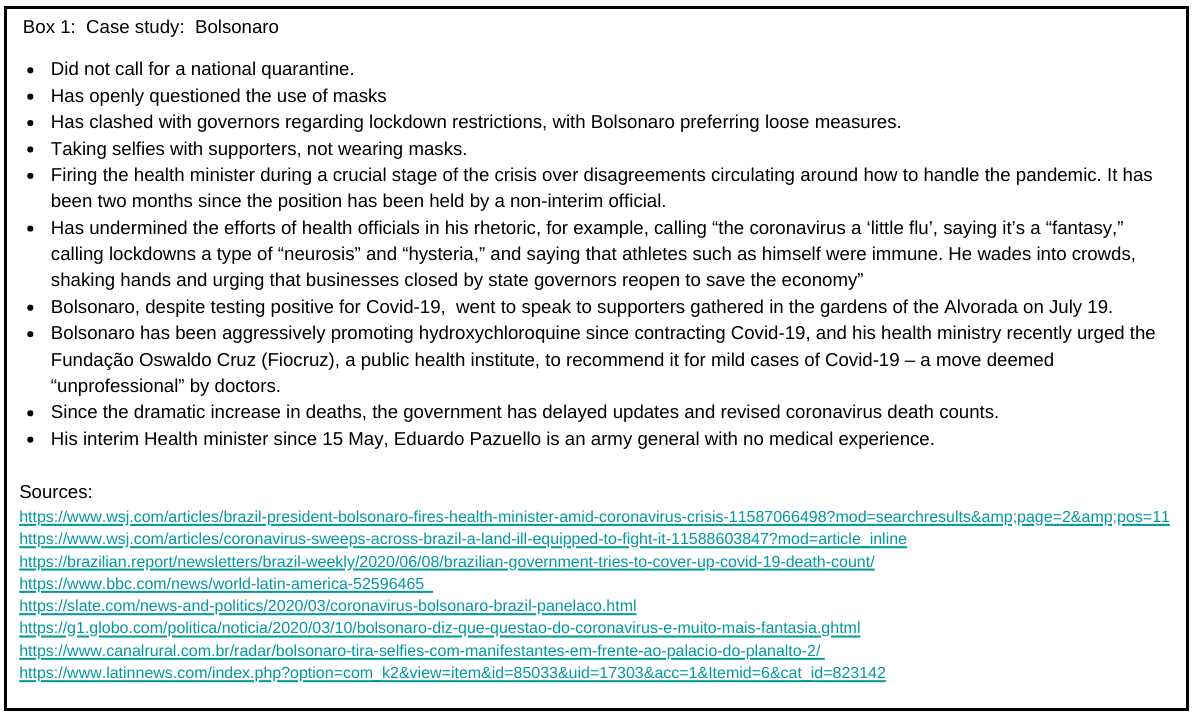

Autocratic opportunists are governments using the crisis as an excuse to curtail electoral freedoms, checks and balance, and civil liberties. In Europe, Hungary is perhaps the best example. It could be argued that Venezuela, already an autocracy and facing a humanitarian crisis prior to the pandemic, falls in this category. It has imposed one of the strictest lockdowns in the Americas, which conveniently reduces the incidence of protest and the demand for scarce gasoline. It has banned scientists, reporters, and medical professionals from reporting stories about the country’s inadequacy in responding to the crisis. And it is taking advantage of the country’s paralysis to intervene in political parties and change electoral rules for parliamentary elections. One could also argue that Añéz’s caretaker administration in Bolivia has come close to entering this category. Añéz initially used the crisis as an excuse to postpone elections. However, a number of members of the opposition have been forced to schedule elections. Uruguay, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Paraguay have considered postponing local elections; Chile has postponed a referendum on how to conduct a constitutional reform. It’s unclear whether these are intentional acts of autocratic opportunism or mere health-based precautions.

Fantasists include governments whose response has been impeded and distorted by partial or full denial of the facts presented by recognized experts, and engagement in conspiracy theories. In the Americas, this response has been most commonly associated with countries besieged by populism, polarization, and democratic backsliding.

Under populism, democracy’s informational advantage erodes. Contemporary populist presidents, in their obsession with appearing anti-elitist and secretly wanting to destroy dissent, have popularized the mistrust of technical expertise, the media, public debate, and inconvenient information. In times of the Coronavirus, this mistrust of information has proven lethal.

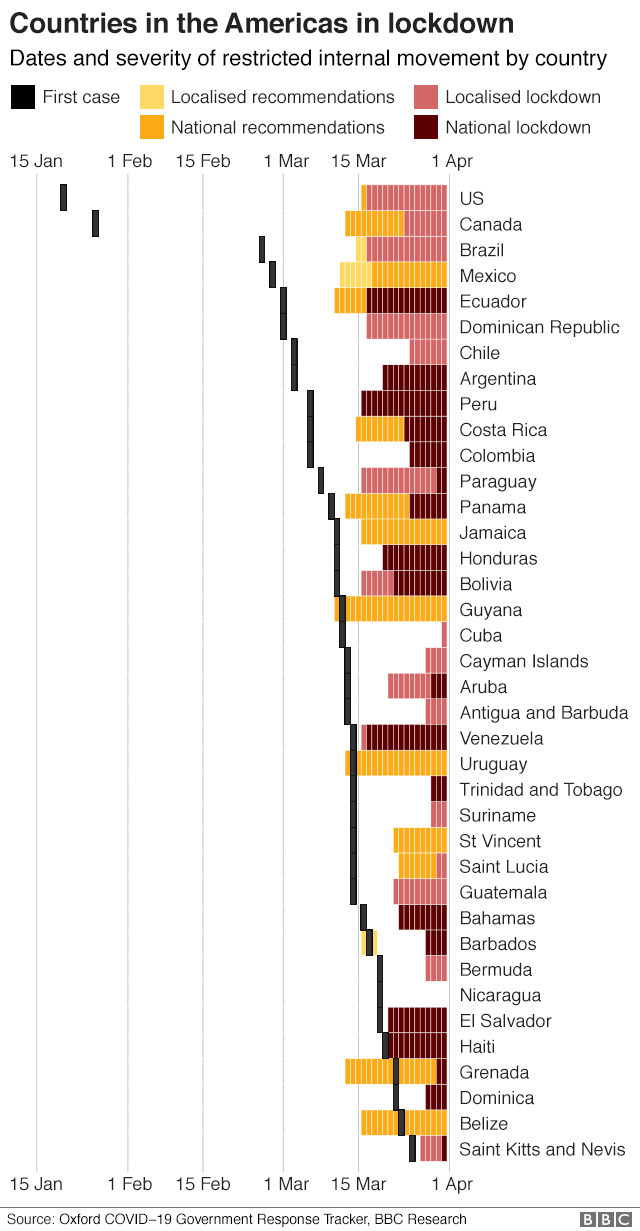

In Brazil, Mexico, and the United States, populist administrations discounted available expert information, leading to periods of denialism and thus wasted time. They took long to respond between the time the first cases were discovered and actual government guideline (see Graph 1). Despite warnings from his health minister, Mexico’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador continued to kiss and hug followers during much of March. And when these presidents finally recognized the need to act, they still preferred to discount the advice from experts, causing confusion across citizens and markets. AMLO in Mexico, like Trump in the United States, adopted a mostly laissez-faire policy, allowing governors to respond as they see fit, rather than encouraging strict nation-wide guidelines. In July, he said experts who study abroad have harmed the country. Populism could very well be the underlying condition that makes democracies more susceptible to death by Coronavirus.

By discounting expert information, populism situates democracies dangerously close to authoritarian regimes. Granted, authoritarian regimes handle crises with original sins that are unimaginable in democracies. For instance, China relied on mass roundup of citizens, invasive surveillance, and political punishments to deal with the pandemic. In the Philippines, the increasingly autocratic president has instructed the police and military “to shoot” anyone violating the lockdown. In the Americas, the two authoritarian systems most committed to suppressing private sector services, Cuba and Venezuela, find themselves with widespread scarcity of goods and health services even before the outbreak began. In Venezuela, there is such a severe shortage of water that hand washing is difficult even in hospitals.

Graph 1

Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747

But a major problem in all authoritarian settings is informational. When authorities in China were first alerted of a deadly virus in Wuhan, they responded by arresting the whistleblower. That initial approach led to denialism, delays in responding, and cover-ups. These delays turned an epidemic into a pandemic. Closer to home, Nicaragua offered another example of autocratic blackout. The dictator Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua disappeared from public for more than a month, during which time, no official response to the Coronavirus was issued. In Cuba and Venezuela, the government has increased crackdowns on any negative information about the outbreak; and in Venezuela, there is very little information about the performance of the health sector.

Admittedly, we often exaggerate the extent to which information flows freely in democracies. Democratic governments also keep secrets. In crises, individuals in democracies abandon what Schumpeter calls “rational volition” in favor of “irrational impulse.”[2] Cognitive biases and information gaps exist in democracies.

However, these biases and gaps become even more pronounced in polarized settings. In irreconcilably divided democracies, voters who support the president won’t change their mind even if information abounds about presidential incompetence. This is because, in polarized environments, one’s team is always better and the other team, always evil. In polarized U.S., for instance, observance of handwashing protocols followed partisan lines. And in Brazil, the president’s supporters attended public protests against Courts and governors for upholding lockdown measures. Few masks were visible, of course (for more on Brazil see Box 1). Like populism, polarization makes information matter less, and thus impairs the ability of democracy to respond well to crises.

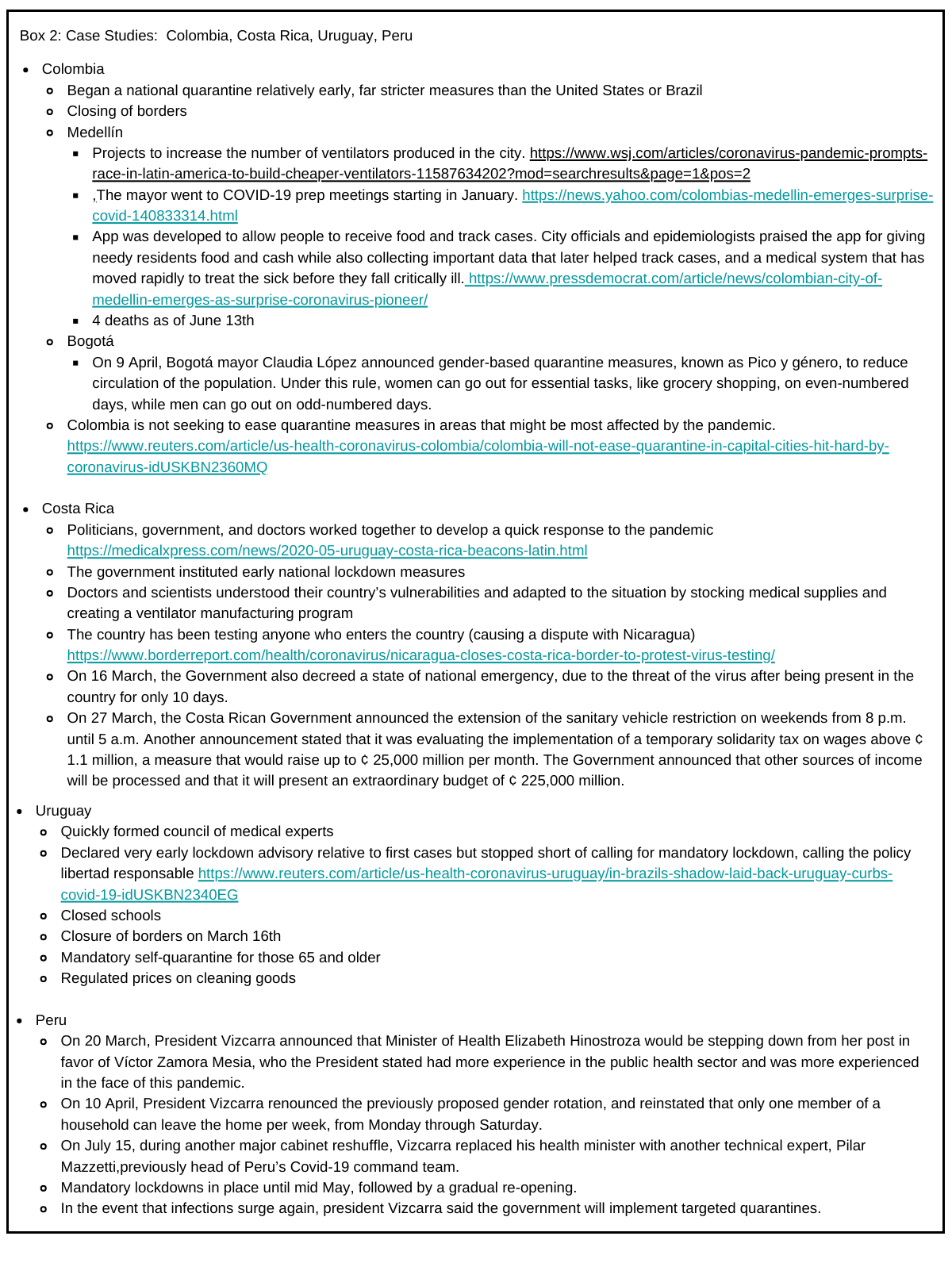

The effective rationalists are governments that act in direct contrast to fanatist/populists. These democracies take a broadly rational and law-abiding approach, based on facts, expertise, and with clear limitations on emergency powers. The world’s best examples are probably Japan, New Zealand, Germany, and South Korea. None of these democracies are governed by technocracy-defying populism. One reason South Korea flattened the curve more quickly than so many other countries is that it was able to test early, and it did so, because its political system learned from experience. The government incorporated rather than dismissed medical lessons from the MERS outbreak of 2015. In the Americas, perhaps the best examples are Canada and Uruguay. Per capita, Canada has had one-third the number of cases as the United States. This was partially due to the higher amount of tests administered in the early stages of the virus. Canada was better able to isolate the infected. However, the success has not lasted as some provinces have failed to provide a sufficient amount of tests. This has led to Canada faring worse than some of the countries led by the effective rationalist governments mentioned above. In Uruguay, which was one of the first cases to respond, the country’s higher than average median age has not been a deterrent to its relative success. It has been helped by having a strong public health system, low poverty rates, and low labor informality rates.

The final category, constrained rationalists, are those governments that follow the same approach as the effective rationalist, but have limited state capacity. Latin America’s better-responding cases fall here. It is also clear economics, not just political cleavages, separate democracies from each other. Democracies with weak welfare states and paltry employment insurance programs, such as the United States, are generating epochal levels of unemployment. Democracies plagued with poverty, such in Latin America, are likely to generate large death rates. These democracies have neither the resources nor the health systems to cope. If rich countries, which on average have 5.6 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants are overwhelmed with Coronavirus, imagine Ecuador’s predicament with only 1.5 hospital beds. It is not surprising that authorities in Guayaquil were picking up dead people from the streets when the pandemic hit.

However, within this category of resource-strapped democracies, three countries that best exemplify the rationalist approach are Colombia, Costa Rica, and to some extent Peru. Unlike the United States and Brazil, Costa Rica and Colombia declared complete national lockdowns shortly after their first cases. Uruguay did not require a lockdown, but did give national lockdown recommendations before their first case was discovered. Colombia has lockdowns and virus mitigation efforts on both national and local levels, some of which have seen great success such as in Medellín. In Peru, rather than dismissing technical experts from the cabinet due to their warnings, the president actually dismissed experts from his cabinet to appoint even more specialized health officials. See Box 2 for details of these pro-information, pro-expertise approaches.

Finally, it is important to consider, not just government characteristics, but also other political institutions. In a widely-read article, Giraudy et al. (2020) emphasized institutions such as party system and federalism to explain the differences between Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Where the ruling party is strong and has nationwide roots (Peronists in Argentina), there can be nationwide compliance with government rules. Where a populist president confronts a strong congress or strong governors (Brazil and the US), the bad responses by the Executive branch can be countered by some helpful economic measures from congress and some governors.

EFFECTS

Does the government’s approach to the crisis matter in terms of outcome? I propose to measure the effects of these policies by looking at two indicators: 1) approval ratings; and 2) ability to contain the Covid-19 deaths.

Approval Ratings

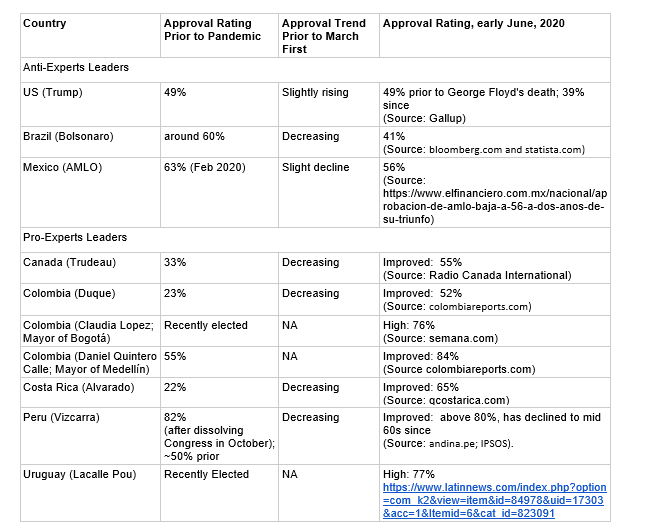

Lockdown measures that become too strict or too long-lasting can be polarizing, splitting the public between willing adherents and those facing an urgent financial need to return to their daily lives. It’s therefore not easy for presidents to maintain high approval ratings during a long lockdown period.

Having said that, the evidence from the first three months suggests a divide in approval ratings. The fanatist/populist approach has produced declines in approval ratings (although in Brazil, ratings were trending down). The pragmatist approach, in contrast, has produced real improvements in presidential approval ratings (see Table 1).

Table 1: Selected Presidential Approval Ratings Before and After the Pandemic

These ratings are of course unlikely to stay as is. Quarantine measures are unpopular and over time, they produce discontent and even rage. In Colombia, Duque’s and López’s approval ratings dropped since May, as authorities were forced to reinstate lockdowns in major cities. In addition, presidents can find a way to recover popularity. Nevertheless, these polls suggest that the Latin American public can reward politicians willing to work with technical experts and punish those who politicize and dismiss technical expertise.

Ability to contain the crisis

Health indicators are probably not ideal ways to gauge the effects of government response. The response of the virus (e.g., reproductive rate, death rate) in a given population depends on many factors other than the government’s response: income levels, age distribution, population densities, size of the informal economy, degree of mobility within the country, pre-existing health facilities, and the population’s relative risk-propensity.

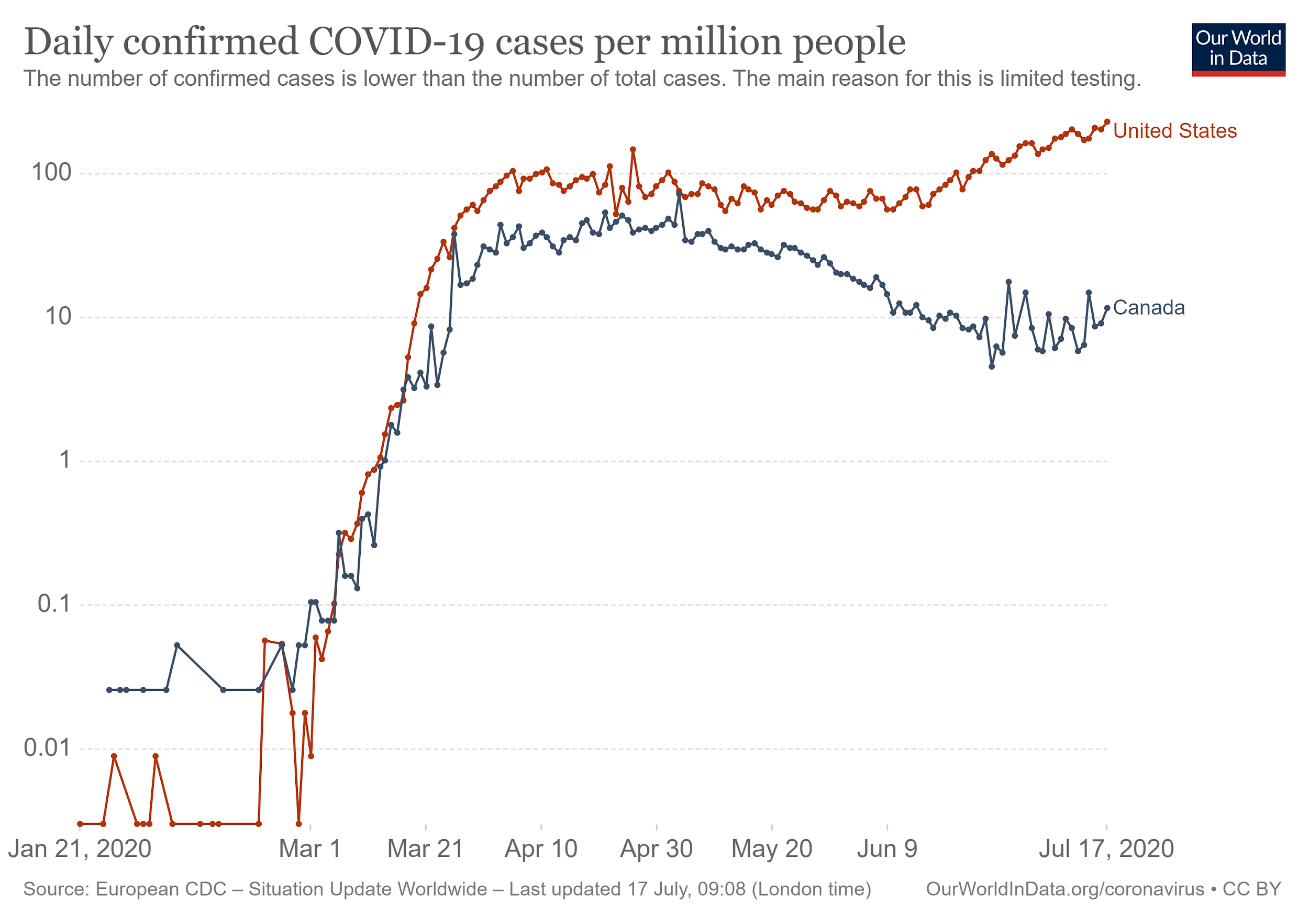

Having said that, we should not be surprised to see some authoritarian governments having greater success (especially those with low consumption rates), because they can impose the harshest penalties on the population for violating protocols. At the other extreme, fanatist/populists should be offering worse outcomes. Graph 2 compares the enormous difference between the United States (anti-expert populism) and Canada (pragmatist) in containing the spread.

Graph 2

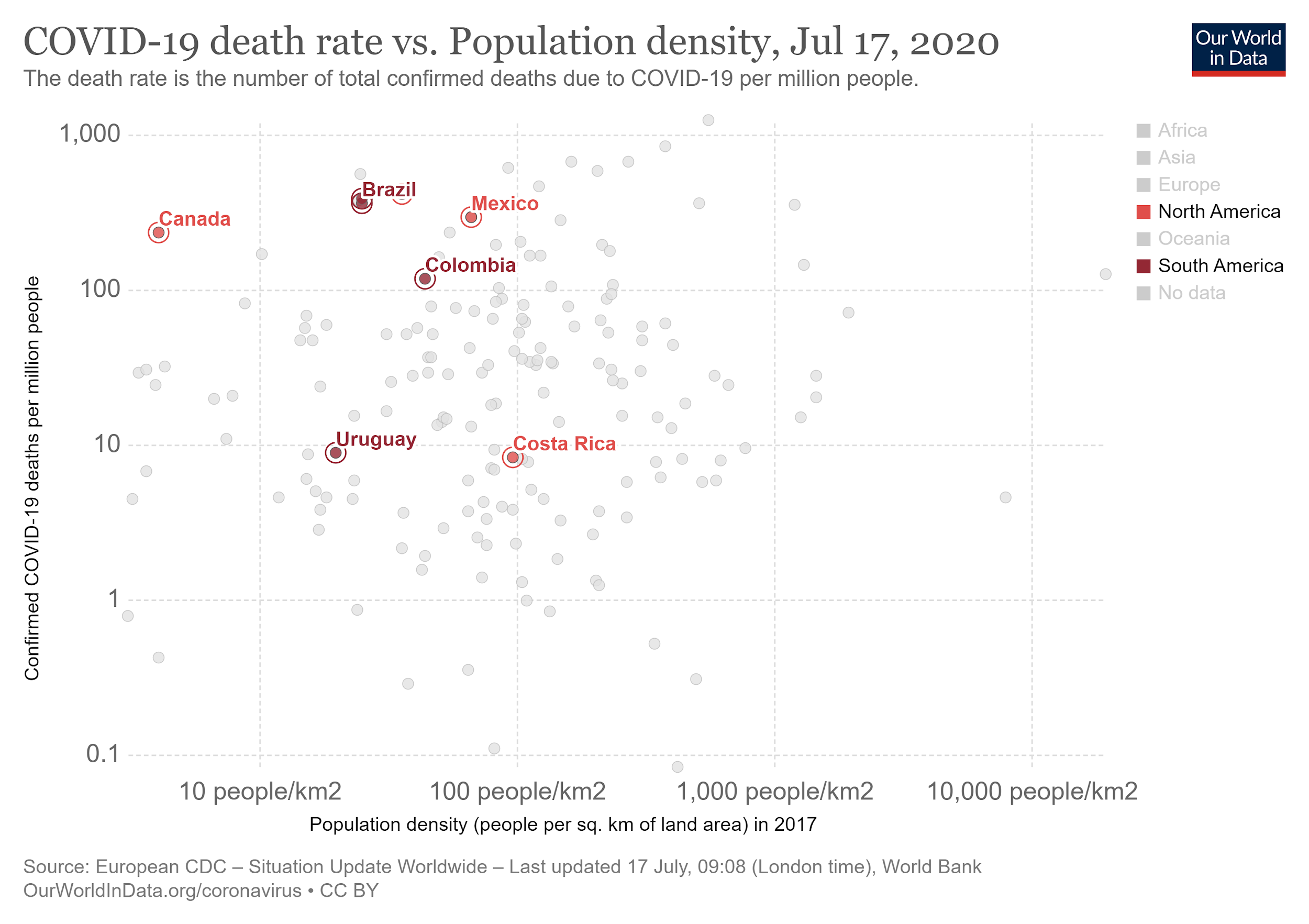

Graph 3 shows that the populist cases, Brazil and the US, despite their lower population density, have a much higher COVID-19 death rate than Colombia and Costa Rica.

Graph 3

Source:https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-19-death-rate-vs-population-density?country=BRA~CAN~COL~CRI~MEX~PER~USA~URY

Note: The United States and Peru have a very similar death rate to population density as Brazil.

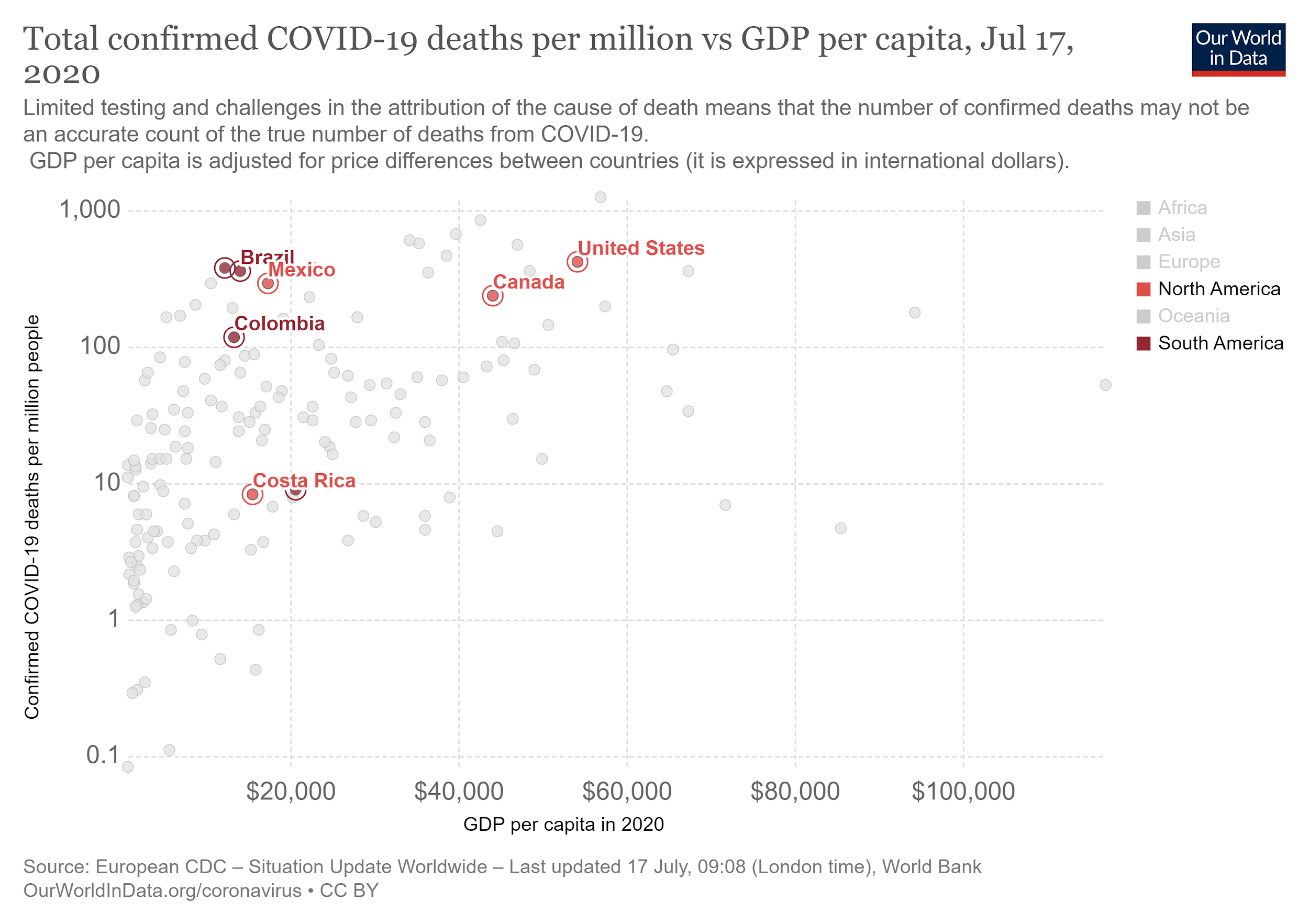

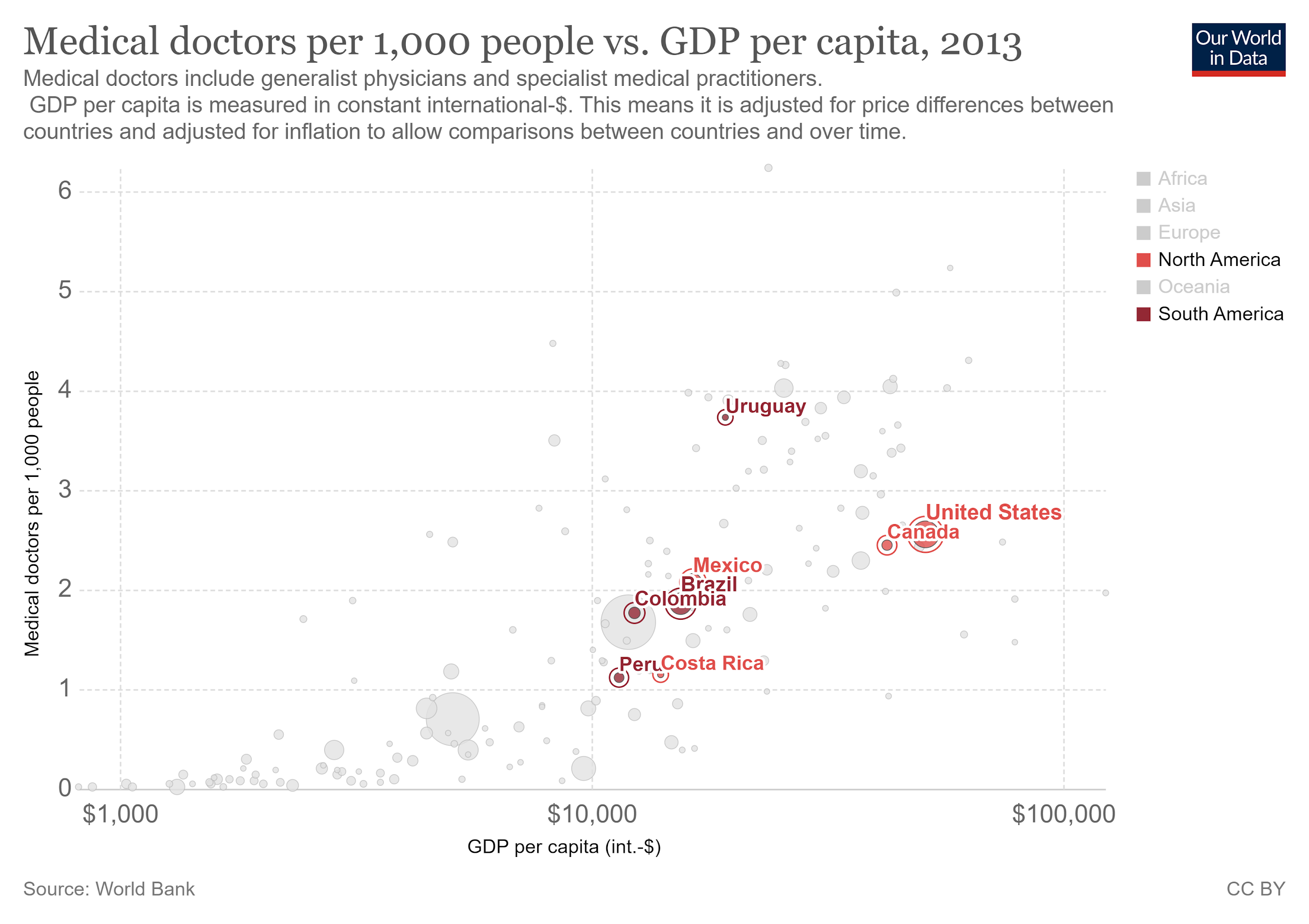

Graphs 4 and 5 show that wealth and health disparities do not account for the difference within Latin America. Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica have comparable wealth and medical doctors per 1,000, but they exhibit different death rates.

Graph 4

Note: Peru has had a similar amount of deaths per million in respect to its GDP per capita as Brazil. The same is true for Costa Rica and Uruguay.

Graph 5

Note: 2013 is the year with the most recent data where all 8 examples can be compared on the same graph.

Conclusion

The Coronavirus has tested the world’s most important regimes, dictatorships and democracies. One could argue that under lockdown, life in democracies is not that much different than life in dictatorship. And once they decide to act, democracies offer responses that can be as impressive as the most efficient top-down autocracies.

But those commonalities should not blind us to the particular weakness of different regimes, and especially democracies led by populists, split by polarization, or featuring weak social programs. These democracies offered the worst initial responses to the pandemic.

[1] Gerald Daly, Tom. 2020. Securing Democracy. Australia’s Pandemic Response in Global Context. Melbourne School of Government, Governing During Crisis Policy Brief No. 1, University of Melbourne, at https://www.democratic-decay.org/governing-during-crises

[2] Schumpeter, Joseph. 1947. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers. Chapters 21 and 22. https://b-ok.cc/book/529436/fd0808