A German Miracle? Crisis Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Multi-Level System

Markus B. Siewert, Stefan Wurster, Luca Messerschmidt, Cindy Cheng and Tim Büthe

As of mid June 2020, approximately 188,500 people have been infected by the novel COVID-19 virus in Germany ultimately resulting in around 8,800 deaths.[1] Even though COVID-19 posed a serious threat to the German healthcare system, the German government was able to cope with the crisis better than most other large Western countries, including the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Spain. Particularly noteworthy is that Germany’s relatively effective response to the pandemic took place in the context of a multi-level system with power-sharing between the federal, state and local levels. Germany’s “exceptional performance”[2] thus raises a set of questions, which we address in this article: How did different levels of the German government develop policies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic? To what extent did the COVID-19 crisis in Germany change the distribution of power in favor of the executive branch? And did the crisis lead to a centralization of competencies from the state/local level to the federal level?

Actions Taken to Address the Imminent COVID-19 Crisis

According to the German constitution (hereafter, Basic Law), the federal government can unilaterally declare a state of emergency in the face of a pending external threat (Art. 80a and Art. 115) or, more importantly in case of the COVID-19 pandemic, an acute interior crisis (Art. 35(2), (3) and Art. 91). Such a declaration allows the federal government to claim substantial competencies to manage a particular crisis without much consultation with, or input from, the Bundestag and the Länder – yet, the state of emergency must be rescinded upon request by the Bundesrat, the assembly of the Länder governments. In contrast to other European countries like France, Italy or Spain, the German government did not make use of these constitutional provisions when it became clear by mid March 2020 that the spread of COVID-19 could not be localized and controlled.[3] The government’s hesitation to invoke constitutional emergency powers may be explained by history – due to the abuse of emergency powers during the final years of the Weimar Republic, which destroyed democracy and the rule of law and contributed to the rise of Hitler, these provisions have never been used since they were belatedly and very controversially added to the Basic Law in 1968 – but it also was unclear whether the COVID-19 pandemic met the requirements of the Basic Law to justify the announcement of an internal emergency.[4]

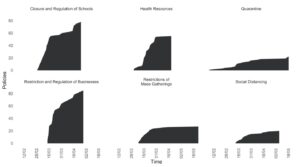

Even though the federal government refrained from invoking emergency powers, Germany used other, sometimes drastic instruments to combat COVID-19. Figure 1 gives an overview of the most important measures adopted at the federal and state level over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, drawing on the CoronaNet database.[5] In addition to ramping up health resources, federal and Länder governments introduced physical distancing measures, quarantines for the infected, the closure of universities, schools, and daycare facilities, restrictions on (including for some time the outright prohibition of) mass gatherings like concerts, soccer games or religious services, and a wide-ranging shutdown of businesses that were deemed “non-essential”. As shown in the graph, most measures were first introduced between mid-March and the beginning of April, when most of the policies peaked – with exception of the regulation of businesses and schools.

Figure 1: Measures Taken over Time in Germany to Cope with the COVID-19 Epidemic

Note: The x-axis indicates the date while the y-axis shows the cumulative amount of policies that have been implemented since the outbreak of COVID_19. “Closure and Regulation of Schools” captures regulations (e.g. closed completely, allowed to open under certain conditions) of different schools (e.g. preschools, universities) “Health Resources” captures information on the distribution and/or production of health resources such as masks. “Quarantine” captures policies which subject people to quarantine and records the conditions of quarantine (e.g. self-quarantine, government quarantine). “Restriction and Regulation of Businesses” captures regulations of private, commercial activity (such as closing markets, reducing opening hours, etc.). “Restrictions of mass gatherings” captures what regulations on whether citizens are allowed to gather for certain reasons or not (e.g. cancellation of recreational events). “Social Distancing” records policies which ask people to socially distance or wear masks in public spaces. Source: CoronaNet database, June 2020.

Practically overnight, the governments’ actions put a hold on all aspects of public life in Germany. However, in comparison to France, Italy or Spain, restrictions were less harsh. For instance, in Germany people were generally allowed to exercise outside, go for a walk or shop for groceries with their partners and families – which was not possible in those countries which issued a comprehensive lockdown. The decision to introduce these policies came on March 15th and 16th after the public demanded a more unified approach to crisis management. By then, the Merkel government and the 16 heads of the Länder had negotiated a shared set of guidelines, as is common in Germany’s system of interdependent executive federalism. These were then executed via the Protection Against Infection Act[6] enabling the federal, state and local authorities to take far-reaching measures to cope with the health crisis. Furthermore, on March 27th, the Bundestag declared a nationwide epidemic[7](“epidemische Lage von nationaler Tragweite“) on the legal basis of the Protection Against Infection Act which equipped the national and subnational executives with additional powers to combat the spread of COVID-19.

Executive Overreach and Resistance in Parliaments, Courts and the Streets

The governments’ actions to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic were contested from the beginning. Before declaring the state of national epidemic, the Bundestag hastily passed a reform of the Protection Against Infection Act. In doing so, the parliament granted the federal health minister a set of new competencies in times of health crises – a draft version even allocated the right to declare the state of national epidemic to the health minister and not the Bundestag. This provision, which puts the health minister into the position to use these new powers without consultation with the cabinet or the chancellor, giving sole prerogative to the health department, drew strong criticism.[8] At a minimum, the Bundestag ensured, via the introduction of sunset clauses, that the most critical regulations would be evaluated within a year, or would otherwise expire.

The issue of how some measures affected existing power structures aside, a number of legal experts questioned the constitutionality of other measures, which temporarily suspended fundamental rights such as the freedom of movement, of assembly, of religion, and of profession.[9] Some criticized, in particular, the curfew policies, which were implemented via executive decrees and administrative acts without a vote in the Bundestag and/or the Länder parliaments, as an act of voluntary self-disempowerment (“Selbst-Entmächtigung”) of the legislatures.[10] This was also echoed by Hans-Jürgen Papier, former president of the German Supreme Court, who stated that policy measures adopted to address COVID-19 were within the limits of the Basic Law but added that massive restrictions of constitutional rights over a longer period of time would require the approval of the legislature.[11] The outgoing president of the Supreme Court, Joachim Voßkuhle, on the other hand expressed his support for the governments’ decisions during the crisis and stressed the resilience of the rule of law in Germany.[12]

The courts certainly proved to be a vital watchdog for the protection of personal freedoms. By mid June 2020, there were approximately 800 legal proceedings at the federal and subnational level which sought to adjudicate whether policies implemented in response to COVID-19 unduly affected individual personal freedoms.[13] Although the overwhelming majority of these cases were decided in favor of the government, there were some prominent exceptions: In Saarland, for instance, the constitutional court ruled against the states’ physical distancing measures as being too restrictive. In addition, the German Supreme Court held that the right of assembly cannot be categorically suspended by the government authorities, but proposals for public assemblies must be reviewed on a case by case basis.

Moreover, Germans largely maintained their right to protest against government actions on the streets. Starting in several larger cities, such as Munich, Nuremberg, Stuttgart, Hamburg and Berlin, rallies against the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic quickly expanded throughout Germany in late April and May. People attended these demonstrations for various reasons: some were genuinely concerned about the restriction of personal freedoms and feared the erosion of democratic principles, others criticized the government measures as too excessive, calling the treatment worse than the disease. Many of these demonstrations were also fueled by conspiracy theories, and by late April also provided a platform for the far right to further polarize German society.[14] The overwhelming majority of the population, however, sympathized with and supported the restrictions and regulations imposed by the government. A nationwide poll in April, for instance, showed that 72% of all respondents were satisfied with the governments’ handling of the COVID-19 crisis, and approval remained high throughout May at 67%.[15]

Crisis Management in the German System of Cooperative Federalism

The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a stress test for the German federal system. Many issues that needed to be regulated in the wake of the crisis fall under the jurisdictions of the Länder including, for instance, policies related to schools, kindergartens and universities, as well as those related to businesses. Moreover, in the German system of cooperative federalism, the states are in charge of executing the laws, and no exception was made for the Protection Against Infection Act. Indeed, the majority of measures resulting from this act have to be implemented through the Länder and not the federal government. In other words, “[t]he Federal government can only make recommendations and must then hope that the authorities of the Länder will comply.”[16]

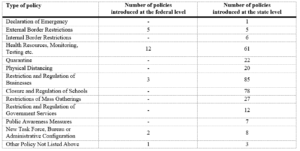

Using again data from the CoronaNet database, Table 1 shows that the states were largely responsible for the introduction of a broad range of policy measures. The regulation of schools, mass gatherings as well as physical distancing and quarantine measures exclusively fell to the states, while the federal level exerted its responsibility with regard to travel restrictions and border closures as well as ramping up the production of relevant health resources.

Table 1: Policies Addressing COVID-19 at the Federal and State Level in Germany

Source: CoronaNet Project, June 2020.

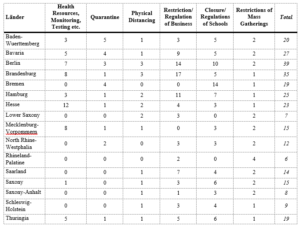

The only Land that declared a state of emergency was Bavaria. Yet, this is not the only difference between the Länder – Table 2 demonstrates that there was significant variation among states in terms of their level of policy activity. Berlin and Brandenburg rank among the most active ones with 39 and 35 adopted policies, trailed by Bavaria (27), Hamburg (25) and Hesse (23); Lower-Saxony and Rhineland-Palatine on the other hand showed much less activity with only 7 and 6 measures, respectively. Similar differences can also be observed with regard to most types of policies administered by the Länder.

Table 2: Selected Policies Addressing the COVID-19 Epidemic Differentiated by Länder

Source: CoronaNet Project, June 2020.

While this variation in the Länder policies was frequently criticized in the public discourse as piecemeal or hodgepodge, the German system of cooperative federalism actually performed (surprisingly) well – albeit only after initially failing to deliver the nuanced and differentiated responses that should be its strength. When it became clear in early-mid March that the pandemic constituted an acute, major threat to public health in (parts of) Germany, the severity of the initial outbreak (and the speed with which the infection was spreading) varied greatly across and within states. Yet, the 16 Länder governments (irrespective of political persuasion) and the federal government quickly converged on common strategies for controlling the spread of the virus. To “flatten the curve,” the states initially all copied virtually every restrictive measure adopted by any one of them within a few days of the first one doing so (often with the blessing or even at the urging of national public health experts, especially the epidemiologists at the federal Robert-Koch-Institute).[17] Such mimicry (during which policy adoption occurred much too quickly to be based on an assessment of the measure’s effectiveness) gave way to differentiated responses when the states began to loosen restrictions in late April/early May. In this third phase of the pandemic response, state and local governments started to adapt measures to local conditions, using the institutions of German federalism to experiment and adopt policies tailored to specific conditions and needs.[18] The competition between the Länder has intensified during the current, fourth phase of the crisis management with several governments trying to outdo each other in developing strategies to restart public life. Any semblance of a harmonized strategy of the federal government and the 16 state-level governments ended when Winfried Kretschmann, prime minister of state in Baden-Wuerttemberg, announced on May 26th that the COVID-19 crisis was now the “exclusive matter of the Länder.”[19] In the absence of coordination, discrepancies in how the states handle the health crisis have further increased, with some lightly affected Länder like Thuringia loosening much more quickly and/or comprehensively compared to, for example, Bavaria or Baden-Wuerttemberg.

Conclusion and Outlook

Crises always shine a spotlight on the executive branch. However, the governments at the federal and state level in Germany have repeatedly emphasized that the measures implemented to address the COVID-19 pandemic are exceptional. In her address to the nation on March 18th, Chancellor Angela Merkel, for instance, called the COVID-19 pandemic the greatest challenge “since German reunification, no, since the Second World War”. She continued, stating that “I know how invasive the closures that the Federation and the Länder have agreed to are in our lives, and also in terms of how we see ourselves as a democracy. […] such restrictions can only be justified if they are absolutely imperative. These should never be put in place lightly in a democracy and should only be temporary.”[20]

Looking back at the management of the COVID-19 crisis in Germany, the implemented restrictions had broad support from the public, and both the federal and the state governments largely received high grades for their actions. Even if tough measures, which have proven to be effective in combating the crisis, have been taken, the rule of law remained intact and the courts curbed measures that they deemed to excessively restrict civil liberties and personal freedom. Meanwhile, public discourse in parliament, the media and on the streets over the governments’ measures adopted to address the health crisis has been and remains vibrant. The risk that Germany might come out of this crisis as a defective or fragile democracy therefore appears very low.[21]

Yet, German democracy has not been wholly unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Will it come out of the crisis permanently altered? It seems highly likely that the competencies granted to the federal government via the Protection Against Infection Act will be revisited and reevaluated by the Bundestag and the Bundesrat once the pandemic is no longer an imminent threat. We also anticipate at that point a larger debate regarding the optimal distribution of crisis management functions and competencies between the federal and the state level. While critics lament coordination efforts, inertia and lack of unity in the existing system, proponents underscore the strengths of a differentiated and subsidiary approach of crisis management, which they argue is much better able to adjust for local conditions and facilitates the innovation of alternative instruments to address crises. Finally, since money always comes with strings attached, it will be interesting to observe whether the federal government will gain new leverage over state and local policies through the economic stimulus packages that have been created to address the economic and societal fallouts of this crisis. In the past, this has often been a gateway for federal encroachment on the competencies of the states.

[1] See the data provided by the Johns Hopkins University, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (last accessed 16 June 2020).

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/04/world/europe/germany-coronavirus-death-rate.html (last accessed 14 June 2020).

[3] For an overview, see Binder et al. (2020): States of Emergency in Response to the Coronavirus Crisis: Situation in Certain Member States. European Parliamentary Research Service, PE 649.408 – June 2020. Brussels.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/649408/EPRS_BRI(2020)649408_EN.pdf (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[4] https://www.hertie-school.org/en/news/detail/content/verfassungsblog-coronavirus-emergency-measures-and-germanys-basic-law (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[5] The database documents measures across various dimensions, e.g. the type of policy; entities targeted by the policy; and the time of implemented as well as duration. As of 8 June 2020 (final data download), the CoronaNet database covers more than 13,000 policies by 198 countries at national, provincial and municipal levels. See Cindy Cheng, Joan Barceló, Allison Spencer Hartnett, Robert Kubinec, and Luca Messerschmidt, “COVID-19 Government Response Event Dataset (CoronaNet v.1.0).” Nature Human Behavior (2020, forthcoming); see also www.coronanet-project.org (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[6] https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ifsg/IfSG.pdf (last accessed 11. June 2020).

[7] Note that while COVID-19 is a global pandemic, in the context of the discussing the German government’s jurisdiction to address COVID-19, it is an epidemic.

[8] https://verfassungsblog.de/parlamentarische-selbstentmaechtigung-im-zeichen-des-virus/ (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[9] See, for instance, https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/corona-massnahmen-rechtmaessig-101.html, https://verfassungsblog.de/fighting-covid-19-legal-powers-and-risks-germany/, or https://www.hertie-school.org/en/news/detail/content/verfassungsblog-coronavirus-emergency-measures-and-germanys-basic-law (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[10] https://verfassungsblog.de/parlamentarische-selbstentmaechtigung-im-zeichen-des-virus/ (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[11] See https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/coronavirus-grundrechte-freiheit-verfassungsgericht-hans-juergen-papier-1.4864792?reduced=true; https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/christina-lambrecht-und-hans-juergen-papier-freiheit-oder-sicherheit-was-zaehlt-mehr-a-00000000-0002-0001-0000-000170716174 (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[12] https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/verfassungsrichter-zur-coronavirus-krise-vosskuhle-haelt-deutsche-strategie-fuer-alternativlos/25833224.html (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[13] https://dejure.org/corona-pandemie (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[14] https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/corona-demos-109.html, https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/corona-demos-reax-101.html (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[15] https://www.infratest-dimap.de/umfragen-analysen/bundesweit/ard-deutschlandtrend/2020/april/, https://www.infratest-dimap.de/umfragen-analysen/bundesweit/ard-deutschlandtrend/2020/mai/ (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[16] https://verfassungsblog.de/fighting-covid-19-legal-powers-and-risks-germany/ (last accessed 11 June 2020). The same would have applied under Art 35 Basic Law since in contrast to other federal states the German constitution does not centralize authority at the federal level in case of an emergency.

[17] See Tim Büthe, Luca Messerschmidt and Cindy Cheng, “Policy Responses to the Coronavirus in Germany.” In The World Before and After COVID-19: Intellectual Reflections on Politics, Diplomacy and International Relations, edited by Gian Luca Gardini. Stockholm – Salamanca: European Institute of International Studies/Instituto Europeo de Estudios Internacionales, 2020: 97-102.

[18] https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2020-05/corona-krise-deutschland-foederalismus-lokale-schutzmassnahmen-lockerungen (last accessed 14 June 2020).

[19] https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/kretschmann-corona-politik-wird-alleinige-laendersache-16786818.html (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[20] https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/coronavirus/-this-is-a-historic-task-and-it-can-only-be-mastered-if-we-face-it-together–1732476 (last accessed 11 June 2020).

[21] https://www.v-dem.net/en/our-work/research-projects/pandemic-backsliding/; for a more critical perspective, https://www.democracy.blog.wzb.eu/2020/04/09/wenn-die-exekutive-viral-geht (last accessed 11 June 2020).

Share this post: