Aline Burni and Benedikt Erforth

As of May 6, France is among the European countries hit hardest by the Coronavirus outbreak, with 25,531 confirmed deaths, ranking only behind Italy (29,315), the UK (29,427) and Spain (25,613) in the region[1]. In Europe, the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in France, on January 24. However, an initial national response plan by the Ministry of Health only came in late-February. In the midst of the outbreak, on February 23, Olivier Véran was nominated as the new Minister of Health, after the then Minister of Health Agnès Buzy laid down her mandate in order to run as mayoral candidate in the municipal elections in Paris.

Mid-March President Emmanuel Macron addressed the nation in a televised speech[2] declaring that France was at war; at war against a virus. It followed the declaration of a health emergency paired with a general lockdown of the entire country, which will not be lifted before May 11. The lockdown was initially put in place for a period of 15 days, during which citizens were only allowed to leave their homes to go to and from work (in case remote work was not possible), to shop for essential grocery items, to see a doctor, to organise the care of children and the elderly, and to individually exercise outdoors (no further than 1km distance from home). For each exit, citizens were obliged to fill in and carry a form with them, attesting the reason for their movement. Since the starting date, on March 17, the set of measures has been renewed twice, on March 27, and again on April 13. At the time of writing, the Prime Minister Édouard Philippe, in light of a prospective deconfinement, introduced a new bill urging an extension of the state of health emergency until the end of July.[3]

The initial phase of crisis management was characterised by a considerable institutional confusion, followed by a strong centralisation of the crisis response. The lockdown in France has been one of the strictest in Europe, but the government was criticised for not acting early enough[4]. Macron was accused of neglecting the seriousness of the situation in early stages and of making major communication mistakes[5]. Still, unilateral measures are not unusual within the French political and legal context, and the adopted response remained within the boundaries of the Constitution.

“France is at War”

Shortly after Emmanuel Macron addressed the nation on March 16, the government presented a law to implement a state of health emergency (état d’urgence sanitaire) in response to the pandemic. The state of health emergency was authorised by law (Loi n° 2020-290[6]) on March 23. The bill was adopted by Parliament, which approved the delegation of special powers to the government for a limited period of time.

According to its art. 2, “a state of health emergency may be declared in all or part of the French territory… in the event of a health disaster endangering, by its nature and severity, the health of the population”. The text[7] provides a legal base for the extraordinary measures that have already been imposed since March 16. More specifically, it establishes a state of health emergency for a period of 2 months and authorises the government to pass primary legislation by statute (par voie d’ordonnance) (art. 3).

The emergency law authorised the Executive to restrict or prohibit the movement of persons and vehicles, prohibit persons from leaving their homes other than for strictly necessary needs, order measures to quarantine, and order measures to maintain affected persons in isolation. Additionally, the government could order the temporary closure of shops or institutions, or limit and prohibit any other forms of gathering and meetings. The law also permitted the government to order the requisition of essential goods and services, temporarily control prices, and take the measures needed to make drugs available to patients. All of these measures have to be strictly proportionate to the health risks incurred and the specific circumstances at a given time and place. Furthermore, they must be ended without delay once no longer necessary. The extension of the state of health emergency beyond the initially established two-month duration could only be authorised by law, taking into account the opinion of the Scientific Council as regulated by article L. 3131-19 of the Code of Public Health.[8]

Beyond the immediate sanitary measures, the government was given the mandate to decide over economic relief, provide state aid and protect employees and companies from economic fallouts for a period of three months.

Following the promulgation of the emergency law, the government immediately adopted 25 statutes (ordonnances) to address economic and social consequences of the health crisis. By April 22 the number of ordonnances totalled 46, which covered three broader areas of concern: measures to curtail the pandemic, economic crisis relief, and a set of regulations concerning the interrupted local elections. Through the various different statutes, the government was able to grant state aid to companies and workers, modify judicial and administrative procedures, and postpone the second round of the municipal elections. Some examples of enacted provisions include the prorogation of social assistance benefits, financial support to companies, flexibility of workers’ rights (e.g. paid holidays and maximum working hours), guarantee of funding for the health system, and delay of administrative procedures.

A constitution that has the word crisis in its DNA

France is no stranger to swift crisis responses that are controlled by a few powerful actors in the Executive. The semi-presidential system was designed with the idea in mind that a crisis requires fast decisions that a purely parliamentary system would be unable to deliver. This is explained by the history of the Fifth Republic, which itself emerged from one of the most severe crises France has experienced since the end of the Second World War – the Algerian War. As such, the Constitution has the concept of crisis written on its DNA. From the outset, the French Constitution was conceptualised to unite personal leadership and democratic legitimacy in order to guarantee the sovereignty of the people without sacrificing the iron fist of the state.

According to Jean Garrigues – French historian and among others author of an Erotic History of the Elysée[9] – it is these two contradictory aspirations – the quest for democracy and the bonapartiste desire for state-led authority – that define the French Republic.[10] Extraordinary situations, like the one we are currently facing, do not generate those understandings of the state but simply make them more visible. This interdependence between two traditions is showcased in the interplay between the president who declares extraordinary measures, and the prime minister who defends the action of the government in front of the Parliament.

The question remains as to whether the adopted measures are proportionate to the situation and as such in line with both the Constitution and the fundamental freedoms on which the latter builds. Yet even when tested against this stricter threshold, few observers in France find the state of emergency violating the boundaries set by the Constitution, such as the principles of freedom and democracy.

In addition to being a moment of the Executive, the crisis also constitutes a moment of the president. As a unitary state with a semi-presidential regime and a dual Executive, executive powers are formally shared between the president and the prime minister in France (Elgie 2005, 70-72). This constitutional arrangement notwithstanding, the Fifth Republic is also characterised by a strong hierarchical order that can lean not only toward the Executive as a whole but also make the president “the main political actor in the regime” (Gaffney 2010,5). In addition to the powers accorded to presidents by the Constitution, it is above all political practice that since de Gaulle fostered the role of a Zeus (Cohen 1986) or – in contemporary language – Jupiter at the head of the state.[11] When Macron framed the current pandemic as a state of war, this was not a coincidence but a political decision responding to the narrative frames that define French politics. In that sense, the move can best be understood as an attempt to create a national unity around fighting a common enemy.

A consensual political environment and a weak opposition

The government enacted its response to the Corona crisis in a favourable political environment. In the 2017 national elections, La République en marche could win 306 out of the 577 seats in the Assemblée nationale (AN). Since then, the opposition has been fragmented and weak. Both centre-left and centre-right parties suffered major defeats and have not been able to recover. The populist radical right party Rassemblement national, whose leader Marine Le Pen ran against Macron in the second round of the presidential election, only counts six deputies in the AN.

Similar to a “normal” state of emergency, during this crisis the Parliament has oversight prerogatives over the government. According to Art. L3131-13 para. 1 of the Code of Public Health, “the National Assembly and the Senate are informed without delay of the measures taken by the Government under the state of health emergency” and they “may request any additional information in the context of the control and evaluation of these measures”. In the context of the state of health emergency, Parliament decided to support the government by focusing its legislative activity only on urgent bills related to the COVID-19. Although meetings and face-to-face sessions were drastically limited for sanitary reasons, Parliament continued to oversee the actions of the Executive. For instance, Parliament exercised its oversight duties, by choosing a virtual format for its weekly Questions au gouvernement (questions to the government). Under this format, only the speakers and party leaders physically meet in the hemicycle. In addition, the AN decided to establish a COVID-19 information mission in order to assess the impact and the management of the pandemic in all its dimensions[12].

Minor opposition came mainly from the Left. For instance, during the hearing on the emergency law, some MPs and senators from France Insoumise and the Parti Socialiste expressed concerns over the broadness of the text, claiming that it conflicted with critical points of the labour law.

Approval ratings temporarily on the rise

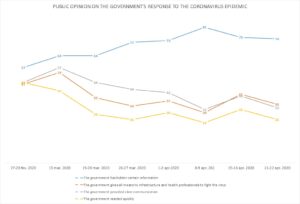

In March, both the president and the prime minister experienced a rise in their popularity rates[13]. Macron saw his approval rating rise by 11 percent (reaching 43 percent), and Philippe by 6 percent (reaching 42 percent). Nevertheless, this short-term spike in approval ratings happens in a context in which citizens increasingly express distrust[14] in the ability of the government to successfully manage the crisis and, more recently, the de-confinement phase. According to a study conducted in late-April by the International Market Research Group[15] (IFOP), criticism towards the government regards lack of transparency, insufficient health infrastructure and equipment, unclear communication, and a slow reaction to the initial outbreak. Since Emmanuel Macron’s televised address in March, dissatisfaction over how the government has handled the crisis has been on the rise (see fig.1). At the beginning, a majority of French citizens approved[16] the strict confinement measures, but this support recently dropped below 50 percent, according to latest polls[17].

Figure 1: Public opinion on the government’s response to the Coronavirus epidemic.

Source: Ifop-Fiducial pour CNews et Sud Radio–Balises d’opinion #93 Suivi de la crise du coronavirus et de l’action gouvernementale –Vague 11

The issue with the local elections

The local elections that fell in the midst of the outbreak soon constituted one of the more controversial issues during the COVID-19 crisis. The first round was scheduled to take place on March 15. At that time, schools and shops had already been closed and the declaration of the state of health emergency was only two days away. In spite of the severity of the situation, Emmanuel Macron decided to hold the elections. Following a consultation of both the National Assembly and the Senate by the Prime Minister, the president – being assured of the support of both houses – decided to maintain the elections. His decision was largely based on the recommendations by the Scientific Council[18]. The president did not want to shed a negative light on the state of French democracy, nor risk being accused of electoral manipulation[19]. Despite preventive health measures on election day, the turnout was historically low (44.66 percent). A considerable number of mayors and local councils were elected in the first round (in 30,000 localities). All remaining candidates are still waiting for a second round. The second round, initially scheduled to March 22, has been postponed to late-June. Should circumstances prevent the second round to be held by then, a new law must be passed and the elections as a whole will have to be repeated across selected communities. There is no major legal controversy about the conduct of the elections, but a question arises with regards to the political legitimacy of those officials who were elected in a context where so many people did not vote fearing for their health.

Final remarks

It is difficult to predict long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis management on the French political system. The executive measures have been taken within the boundaries of the Constitution and do not seem to generate major frictions in the inter-relations of the institutions of the Fifth Republic.

However, effects of the COVID-19 on the current government and its public approval will largely depend on how well France manages the re-opening of its public and economic life. Expectations about the de-confinement phase are rapidly rising, as well as criticism from the opposition and scepticism of the public. Other factors to consider include the re-opening of various different reform negotiations – including the highly contested pension reforms – which, for the time being, have been suspended. In this sense, the agenda of the current president is likely to drastically feel the need to adapt to the circumstances of the crisis and its socio-economic challenges. It is possible that Macron’s initially liberal agenda will move away from its primary objectives of implementing structural reforms. Although in the short-run Macron seems to experience a boost in his approval, similar to what happens with leaders in other countries, his success in the longer run could depend on the role attributed to the French state in the economic recovery.

[1] POLITICO, ECDC, Johns Hopkins University, Muhammad Mustadi, Worldometers (Coronavirus in Europe)

[2] « Nous sommes en guerre » : le verbatim du discours d’Emmanuel Macron

[3] Compte rendu du Conseil des Ministres, 2 mai. https://www.gouvernement.fr/conseil-des-ministres/2020-05-02/prorogation-de-l-etat-d-urgence-sanitaire?utm_source=emailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=conseil_ministre_20200502

[4] How President Emmanuel Macron bungled France’s coronavirus response

[5] https://www.lesechos.fr/idees-debats/cercle/opinion-coronavirus-les-erreurs-de-communication-du-gouvernement-1190699

[6] LOI n° 2020-290 du 23 mars 2020 d’urgence pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19, available on LOI n° 2020-290 du 23 mars 2020 d’urgence pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19

[7] LOI n° 2020-290 du 23 mars 2020 d’urgence pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19 (1), available on LOI n° 2020-290 du 23 mars 2020 d’urgence pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19

[8] Article L3131-19, Créé par LOI n°2020-290 du 23 mars 2020 – art. 2, available on Code de la santé publique – Article L3131-19

[9] Garrigues, Jean (2019). Une Histoire Érotique De L’élysée: De la Pompadour aux paparazzi. Paris: Payot; p. 256 Une histoire érotique de l’Elysée: de la Pompadour aux paparazzi

[10] Coronavirus: “La Ve République n’est jamais aussi efficace qu’en temps de crise”, selon Jean Garrigues

[11] https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-i-dont-see-myself-as-jupiter/

[12] Crise du Coronavirus-COVID19 : conclusions de la Conférence des Présidents

[13] SONDAGE. La popularité d’Emmanuel Macron et Édouard Philippe en hausse en mars

[14] Coronavirus. 56 % des Français estiment que la crise sanitaire est mal gérée par le gouvernement

[15] Suivi de la crise du coronavirus et de l’action gouvernementale – Vague 11

[16] Chez les Françaises et les Français, le confinement fait globalement consensus

[17] France: public support for strict lockdown drops below 50%

[18] The Scientific Council (comité de scientifiques) was established on March 11 in line with Article L3131-19 of the Code of Public Health. Its president is nominated by decree, by the President of the Republic. The Scientific Council provides advice, based on updated scientific evidence, to the decisions of the government to deal with the pandemic. COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE Olivier Véran installe un conseil scientifique pour éclairer la décision publique dans la gestion de la

[19] Coronavirus : Emmanuel Macron «assume totalement» le choix d’avoir maintenu les municipales

References

Cohen, Samy. 1986. La monarchie nucléaire: Les coulisses de la politique étrangère sous la V. République. Paris: Hachette.

Elgie, Robert. 2005. “The political executive.” In Developments in French politics 3, edited by Alistair Cole, Patrick Le Galès, and Jonah D. Levy, 70–87. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gaffney, John. 2010. Political leadership in France: From Charles de Gaulle to Nicolas Sarkozy. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.