Christopher A. Martínez

Introduction

Proposals that seek to do away with presidencialismo are not scarce in Chile. Several scholars, Juan J. Linz and Arturo Valenzuela among them, have suggested—even since the mid-1980s—that Chile needs a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Since the Chilean chief executive is regarded as one of the most powerful in the Americas, proposals to weaken presidential power might not be surprising. However, presidential authority is not as powerful as the Constitution makes it look, and it has declined in the last 20 years. For instance, the president’s power to appoint key positions in the judiciary and other high-rank politico-administrative posts has been curtailed by the 2005 constitutional reforms, the Crime Procedural Reform, and the Senior Executive Service System (Martínez 2018). Similarly, presidents complain that parties and legislators constantly constrain their influence. Still, the president has important tools at her disposal—such as exclusive legislative initiatives (budget included), the authority to declare legislation urgent and regulatory (administrative) powers, consistent claim to the most media attention, and widespread recognition as the center of the political system.

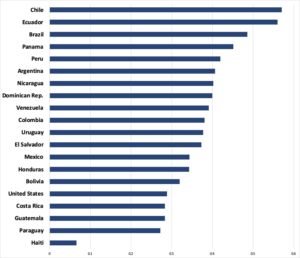

FIGURE 1: Presidential Power in the Americas

Note: Own elaboration based on Doyle y Elgie’s (2015) data. Higher values suggest a more powerful president.

In the next section, I discuss Arellano and Martínez’s (forthcoming) article on Chile’s presidential power deconcentration in the 19th century. Using their theoretical framework, I then analyze whether recent proposals that promote a less presidential form of government are feasible in the short term. I conclude this essay by offering some final thoughts about the future of Chile’s presidencialismo.

Gradual weakening of presidential power in the 19th century

As argued by Arellano and Martínez, very few studies actually analyze what causes variations in presidential power concentration. Most of the literature focuses on the type of powers at the president’s disposal and their reforms rather than explaining what is driving them. Arellano and Martínez study how presidential authority weakened during the second half of the 19th century. During this period, Chile underwent a process of gradual yet resolute power deconcentration, one that was the result of neither regime breakdown nor internal turmoil.

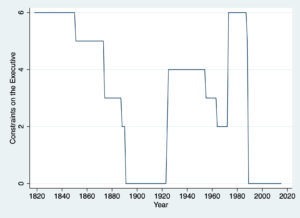

FIGURE 2: Constraints on Chile’s Executive Power

Note: Own elaboration based on data from Polity IV. Lower values suggest stronger constraints on the executive, that is, a weaker president.

Arellano and Martínez theorize and empirically show how events, ideas, networks, and institutional ambiguity work together to produce different types of institutional change. They show that the constitutional reforms were preceded by a shared evaluation that presidential influence needed to be tamed, which was built upon a set of liberal ideas and a network of activists and politicians who rendered these ideas actionable after the occurrence of specific events (critical juncture). Arellano and Martínez also described that prior to the formal reforms, there was an informal change in the actors’ behavior whereby they started to question and challenge presidential authority.

Interestingly, until the 1850s, Chilean politics heavily centered around the president, whose influence was virtually uncontested. Arellano and Martínez explain that everything started to change in the mid-1850s when the conservative ruling coalition split into two factions. The most religious of the two factions left the government because conservative President Manuel Montt had adopted a more adamant stance in favor of greater separation between the State and the Catholic Church. The religious conservative faction then moved to the opposition and forged an unlikely legislative alliance with the Liberals against the conservative faction that remained in power alongside President Montt. Liberals and (religious) Conservatives then came to embrace ideas that questioned the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the president.

These ideas had been sponsored by academic and activist groups since the end of the 1840s. Arellano and Martínez posit that these groups were influenced by the ideals of the 1848 French Revolution and by an increasing unrest about the central government’s growing influence in domestic affairs. But only when Liberals and Conservatives came together did these ideas make it to the heart of the political system. Arellano and Martínez show that during the 1850s and mid-1860s, the legislative opposition began to constantly challenge presidential authority by re-interpreting existing yet unused constitutional rules (institutional ambiguity), such as the interpellation of ministers and the power to reject the president’s budget proposals. Presidential power was dramatically constrained in ways unimaginable only decades earlier. In fact, Congress was a driving force behind cabinet turnover during the second half of the 19th century.

Eventually, all major (proto) parties supported the idea of a less powerful chief executive. By the mid-1860s, there were few and weak veto players that sought to maintain the status quo. Even former President Montt, who backed the idea of a strong executive, began to advocate for a weaker president. Several reforms that dramatically curtailed presidential power were finally approved in Congress by the end of the 1860s and the early 1870s. These reforms ushered in what it was known as the “pseudo parliamentary republic,” which lasted until 1925.

Towards a less presidential political system

Now, let’s go back to the 21st century. In 2017, a group of senators from the Left and the Right revived the idea that Chile should move to a semi-presidential republic, a proposal that resembled one previously introduced by Senator Andrés Allamand in 2016. Perhaps the most thorough constitutional reform proposal comes from Nicolás Eyzaguirre, Pamela Figueroa, and Tomás Jordán (2019).[1] In it, they suggest that the president can dissolve Congress once during the first two years of the 4-year presidential term, that Congress can censure the president and call for new presidential elections, that legislators are allowed to hold cabinet positions simultaneously, and that there be a reduction in the topics on which the president has exclusive legislative initiative, among other changes. According to the authors, the new form of government they proposed is a “parlamentarized presidentialism.”

In the light of these reform proposals, it is necessary to analyze if certain political conditions might enable Chile to adopt a less presidential constitutional government any time soon. As mentioned above, there is no lack of ideas and proposals about modifying Chile’s presidencialismo. The fact that politicians from both the ruling coalition and the opposition, including those who occupy key positions in Congress and their parties, have backed these proposals signals that an agreement among elite members is underway. This is an important step toward institutional change, but one that is not sufficient by itself. Even though ideas and networks seem to have converged, it is less clear if all key political players have a shared evaluation about the problems these reforms would eventually solve. For instance, Senator Allamand (2016) see low trust towards political institutions and limited collaboration between branches as major issues that his proposal might tackle. The senators’ (2017) project, on the other hand, seeks to improve governance and executive-legislative cooperation, which—according to them—have been hampered by recent politico-institutional changes, such as the increase of legislative parties as a result of the new proportional representation electoral system. Finally, Eyzaguirre et al. see that power concentration in the executive hinders executive-legislative relations.

We have not witnessed any major political event (critical juncture) that may fuel or accelerate constitutional change, which is also an important element in Arellano and Martínez’s approach. On the other hand, President Sebastián Piñera does not have a majority in Congress. Even though this makes approval of presidential initiatives harder to achieve and forces Piñera into constant negotiations with the opposition, no serious or destabilizing incidents have occurred.

Concluding remarks

Perhaps, the fractionalization of the Left, and the crises in which some of its main parties find themselves (e.g., the Socialist Party and the Christian Democrats) may help to create favorable conditions for constitutional change. The new composition of Congress, with more and new parties since the electoral reform (first implemented in the 2017 elections), may bring political actors on board to come up with a form of government that bestows more power on Congress vis-à-vis the executive branch. Nevertheless, I do not think that a more fractionalized and still-changing legislature should be given more power in the short term. Before adopting another far-reaching reform such as the ones seeking to reform Chile’s presidencialismo, it would be wise to wait a couple of years until the effects of the new proportional representation system settle down and institutionalize.

References

Arellano, Juan Carlos and Martínez, Christopher A. (forthcoming). Gradual change and deconcentration of presidential powers in Chile (XIX): Ideas, networks, and institutional ambiguity. Polity.

Doyle, David and Robert Elgie. (2015.) Maximizing the reliability of cross-national measures of presidential power. British Journal of Political Science, DOI: 10.1017/S0007123414000465.

Eyzaguirre, Nicolás, Figueroa, Pamela and Jordán, Tomás. (2019). “El necesario cambio al régimen político. Hacia un presidencialismo parlamentarizado.” Paper presented at the research workshop ‘The effects of institutional change in Latin America,’ Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile. August 2019.

[1] Nicolas Eyzaguirre was the Minister of Finance during the Ricardo Lagos administration (2000-2006), and during the second Bachelet administration held the positions of Minister of Education (2014-2015), Minister Secretary-General of the Presidency (2015-2017), and Minister of Finance (2017-2018).