Aline Burni

Scholars have extensively studied the phenomenon of radical right parties. Mainly investigated have been the causes for their emergence and reasons behind their support, but less so the implications they have for democracies and, more specifically, for policy outcomes. What are the repercussions of electorally stronger radical right parties? To what extent are they able to influence the political agenda and policy outputs, more concretely?

Radical right parties are widely present in Europe today. Typical examples are the Italian (Northern) League – LN, the Freedom Party of Austria – FPÖ, the French National Front (now, National Rally) – FN/RN and the Alternative for Germany – AfD. In general, they have significantly increased their public support over the last decades, despite important cross-national variations. My dissertation analyzes the extent to which they are important drivers of a more restrictive immigration agenda adopted by national governments. This is an interesting topic to address, because radical right parties have contributed to the politicization of the immigration issue and, by becoming stronger in elections, they have pushed mainstream parties to respond to their agenda. A lot has been speculated about how they represent a threat to democracies, so it is crucial to understand what the real implications of their rise are in terms of policy agenda.

Over the last years, the issue of immigration has become prominent in European politics, while more restrictive positions on the matter have been at the center of electoral campaigns and governments’ agenda. For instance, in September 2018, the French President Emmanuel Macron passed a controversial asylum and immigration reform, of which one of the aims was to accelerate the treatment of asylum claims. At the time, the left opposition claimed that it was a mechanism to limit the access of refugees to the country, reflecting a stricter control over the entrance of immigrants, particularly of non-Western origin. During the 2017 presidential race, Macron did not explicitly focus on immigration as a priority, but he run the second round against Marine Le Pen (from the National Front party, now National Rally) who is in the spotlight due to her tough proposals to fight “uncontrolled” immigration. Marine Le Pen’s party has long advocated for drastic reduction of immigrant inflow to France and the EU, expressing a similar culturally protectionist view from other radical right parties in Europe.

Another recent example where the immigration agenda gained prominence among mainstream parties and the agenda of governments is Denmark. By gaining larger shares of the votes, the Danish People’s party (DF) forced the Social Democrats to change their immigration discourse. In the last general election, in June 2019, the center-left party managed to regain power following the adoption of a tougher stance on immigration and is now implementing an aggressive anti-immigration policy. The rise and consolidation of radical right parties seems to be an important driver of the increasingly restrictive immigration agenda in Western Europe.

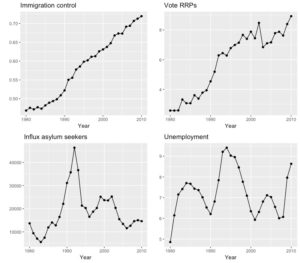

Immigration policy is a multidimensional concept. It concerns different tools (decrees, laws, administrative measures, etc.), locus of implementation (internal or external), and targeted categories of immigrants (such as workers, family members, asylum seekers/refugees, co-ethnics). The area of controls over the entry and stay of immigrants has become particularly stricter over time in the analyzed countries, as shown in the figure below. The figure also shows the evolution of some potential explaining factors driving the immigration policy agenda, which in the image are the vote share of radical right parties[1], the average inflow of asylum seekers[2], and average unemployment rate[3]. From these indicators, there is a trend of more restrictive controls over immigration in Western Europe, closely following the trend of increasing votes for radical right parties.

Figure 1: Evolution of the level of restriction of immigration controls and potential explaining factors, Western Europe (1980-2010)

Source: Elaborated by the author

Radical right parties and immigration policy: how could they influence the agenda?

Radical right parties appeal to identitarian politics, they hold authoritarian values and are characterized by a populist style. Previous research has shown that immigration is a central concern in their platforms and their most important driver of support. Indeed, their position on the immigration issue is much more negative and salient than for other party families, while members of the radical right group are also very homogeneous in this respect. Likewise, it is known that radical right parties have been central actors in the process of politicization of the immigration issue, particularly since the 1990s. By introducing a new issue in the electoral competition, radical right parties have been able to increase their vote share, representing a challenge to established parties, from both sides of the ideological spectrum.

Mainstream parties have implemented a range of strategies to respond to the rise of the radical right. One of the most frequently used is the co-optation of the radical right’s political agenda. This means that mainstream parties start to adopt issues and positions from the challenging radical right. However, the extent to which radical right parties are indeed driving more restrictive immigration policy decisions has not been fully addressed. Previous studies on the topic have shown contradicting results in this regard, usually drawing from few case studies, and privileging situations where the radical right is in government. Some emphasize the limited capacity of radical right parties to advance their policy preferences, for reasons such as internal disagreements or constraints imposed by their coalition partner. However, in other cases, the radical right has been judged pivotal for tougher immigration laws, Italy being one example.

As such, the literature assumes that, and brings evidence to the fact that the rise of radical right parties affects the agenda of other parties, particularly during electoral campaigns, who are forced to address elements of their program. So, to what extent such shifts in mainstream policy positions also have implications for policy-making?

My research investigated the two following questions in a comparative perspective:

1) To what extent do national governments enact more restrictive immigration policies in reaction to the electoral performance of the radical right?

2) By increasing their electoral support, can radical right parties influence immigration policies towards a more restrictive direction, or only when they enter governing coalitions and have the potential to exert a more direct impact?

Radical right parties clearly advocate for stronger controls over the entrance and stay of foreigners. They want to limit their presence in the national territory, sometimes even restricting their rights. As previously explained, the rise of radical right parties represents an electoral challenge for mainstream parties because they introduce a new salient issue that demands responses of traditional parties, and because dominant parties lose important portions of their electorate. In terms of policy, I expected that the reactions of mainstream parties would include the adoption of the radical right agenda and this would reflect more restrictive immigration policies enabled by parties in office.

On the other hand, as discussed by scholars, the emergence of radical right parties can also be a new opportunity of alliance for the center-right (Bale 2003). Therefore, another mean by which the immigration agenda could become more restrictive would be when dominant parties seek support of radical right parties to govern, and the latter have a direct policy influence. This is important to consider because, at this point in time, radical right parties have taken part in government in a number of countries, for instance in Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland. In 2002, the Italian right-wing coalition – which included the radical right parties Northern League and National Alliance – passed a restrictive immigration law, called the “Bossi Fini” law.

Briefly, my argument states that electoral competition has been crucial to understand the policy agenda on immigration over the last years. This is because radical right parties have been able to press governments to adopt more restrictive immigration policies by contaminating the agendas of mainstream parties or by providing support to the government in place, in exchange of desired policies.

Immigration control policies are more restrictive when radical right parties are stronger

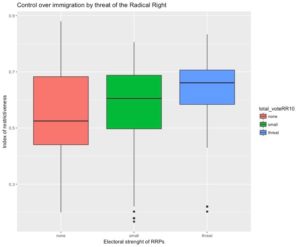

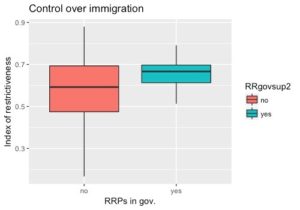

Indeed, my analysis shows that the average restriction level of immigration control policies is higher when radical right parties perform better in previous elections. This also happens when they support the government, either as a formal or informal coalition partner. Figure two, below, displays the average restriction level of immigration controls considering the level of electoral threat represented by radical right parties and their support to the government. Furthermore, multivariate analysis brought additional evidence that the effect of the electoral strength of radical right parties persists as a statistically significant driver of immigration policies, even controlling for alternative explanations. Additionally, their presence in government also has significant effects in the restriction level of immigration controls, even controlling for other factors.

Figure 2: Average levels of restriction of immigration controls by the strength of radical right parties and their support to the government

Note: The left-wing graph shows the average level of immigration control policy by three groups of radical right support (0 percent; between 0 and 10 percent, and higher than 10 percent of the votes in national legislative elections – lower chamber). The right-wing graph shows the average level of immigration control policy according to radical right participation (formal or informal) as a coalition partner. The level of restrictiveness of immigration control policy ranges from 0 (liberal) to 1 (restrictive).

Source: Elaborate by the author

I tested the influence of radical right parties on immigration control policy using an original data set built from secondary sources. The dataset includes panel data of 17 Western European countries between 1980 and 2010. It comprises measures of comparative immigration policies from the IMPIC dataset, as well as political, institutional and economic variables. I developed a model to explain the level of restriction of immigration control policy grounded in four dimensions: electoral competition, characteristics of governments, institutions, and contextual factors. I consider these other factors because the literature on comparative immigration policies discusses them as potentially affecting changes in the area of immigration. For example, immigration policies could become stricter if the volume of immigrants increases, or if the economic situation of the country gets worse.

The main findings of the analyses pointed that, although the indirect effect of radical right parties, through elections, is small and not the single important driver of the agenda, they have been able to influence stricter policy measures of immigration control over time. The electoral threat of radical right parties is, then, a relevant, but not sufficient condition to influence the government’s agenda on immigration issues. Furthermore, I also found that radical right parties could push for stricter immigration control measures when they support the government in place.

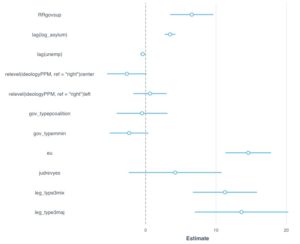

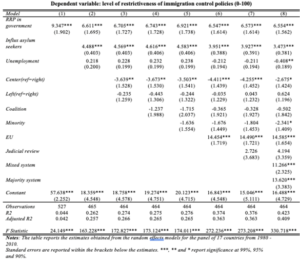

Figure 3: Regression coefficients for immigration control policy level, using radical right party support to the government as independent variable

Source: Elaborate by the author

Overall, there are also other factors relevant to explain the immigration agenda, notably the inflow of asylum seekers, the type of electoral system, the government ideology (with centrist parties displaying a more liberal position), and the European Union. The EU seems to provide an arena in which national governments cooperate to advance their (national) border protection interests, instead of a liberalizing supranational institution, favoring the expansion of (non-EU) immigrants’ rights. Interestingly, the analysis revealed the electoral effect of radical right parties to be stronger in mixed and majority systems, compared to systems run by proportional representation. The two tables below display these results, considering models run separately for majority/mixed systems and proportional representation systems.

Table 1: Estimation Results – Models for majority and mixed systems, using vote for radical right parties as independent variable

Table 2: Estimation Results – Models for proportional representation systems, using vote for radical right parties as independent variable

Contagion effects and the electoral system

Why is the effect of radical right parties’ electoral results on immigration policies higher in systems that are more disproportionate? A plausible explanation is that in mixed and majority systems – which tend to display more distortions between votes and seats than proportional representation systems – the rise of a challenging party can represent a more pronounced threat to established parties, who are then pushed to provide immediate answers in the electoral competition, usually by moving closer to the average voter. In addition to that, in proportional systems, there is place for representation of different actors, while in systems where there are more distortions, smaller changes in vote-share can represent big changes in terms of access to representative institutions and bargaining power. This means that the perceived level of competitiveness introduced by radical right parties could be relatively smaller in proportional representation systems, where there are usually more veto points able to prevent restrictive reforms and counterbalance the anti-immigration pressure of the radical right. Nevertheless, in mixed and majority systems, losing votes to a challenging party can more clearly mean exclusion from power.

This does not mean that radical right parties only affect the policy agenda in majority and mixed systems. In fact, in proportional systems, they can represent a new alliance opportunity for center-right parties, which makes them potential coalition partners. My study confirms, from a systematic analysis, what previous investigations have already indicated: that by entering the government, radical right parties can directly affect the policy-making agenda and advance their anti-immigration pledges. In summary, in mixed and majority electoral systems, the contagious (indirect) effect of radical right parties seems to be higher, while in proportional systems their direct effect is more likely, because of the better chances of becoming a coalition partner, depending on their bargaining power.

Conclusions

My dissertation argued that radical right parties have been able to slowly conduct the immigration agenda towards a more restrictive direction over the last years in Western Europe. They have done so by pressing mainstream parties to adapt their positions in the competition or by gaining access to government. The pathways by which radical right parties affect the immigration agenda can be different depending on the electoral system.

What do these findings imply? On the one hand, they suggest that, despite not being dominant political actors in most party systems, radical right parties can still influence policy outputs, which are also driven by other contextual and institutional factors. On the other hand, the analysis shows that institutions play a crucial role in intermediating political actors’ preferences over the process to become policy outputs (Abou-Chadi 2016). This means that speculations about consequential changes conducted exclusively by the agency of radical right parties can be overstated. Although political actors are important to account for restrictive or liberalizing trends in immigration policies, these actors do not perform without constraints and the interactions among them is also a determinant element to take into account.

By learning that the influence of radical right parties on policy-making tends to have different configurations in proportional and non-proportional systems, this study opens new research questions regarding the dissimilar opportunity structures encountered by radical right parties to influence policy-making under different institutional settings. The fact that radical right parties seem to have a bigger indirect effect on immigration policy-making under majority and mixed systems, compared to systems operating under proportional representation, points out that the former cannot be taken as mechanically barring the growth and influence of radical right parties in particular, and of smaller/third parties more generally. Indeed, it suggests that, when radical right parties are able to gain certain amounts of support when systems are more disproportional, the perceived threat of mainstream parties can be higher, which can be even more consequential for policy.

In general, the study suggests that party preferences water down over the democratic process of policy-making. This applies not only to radical right parties, but also probably to mainstream parties as well, because the latter are apparently significantly shifting their policy positions in the context of party competition (particularly in the field of immigration), but not exactly fulfilling their promises when in office.

Finally, since the balance of forces and the configuration of alliances in Western Europe have gone through major transformations in recent years, it is likely that radical right parties will be a key component in the upcoming political scene. They incarnate an anti-immigration appeal in a context where immigration remains very salient, becoming electorally stronger in many elections. While their electoral support is not necessary and sufficient to change the course of immigration policies, their influence consists an additional component of incremental restrictive changes, which configure the gradual closing of European borders to non-Western immigrants.

This post is based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, entitled Government Agenda under Electoral Pressure: The Impact of Radical Right Parties on Immigration Policies in Western European Democracies (1980-2010). The dissertation was defended in June 2019, at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

[1] Measured as the valid percentage of votes obtained by radical right parties in national legislative elections. The data was collected from the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow 2019).

[2] Measured as the natural logarithm of the absolute number of asylum seekers entering the country per year, collected from the OECD Statistics dataset.

[3] Measured as the number of unemployed, as a percentage of the labor force, collected from the Comparative Political Dataset (Armingeon, Klaus, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. 2018).

References:

Abou-Chadi, Tarik. 2016. “Political and Institutional Determinants of Immigration Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(13): 2087–2110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1166938.

Bale, Tim. 2010. “If You Can’t Beat Them, Join Them? Explaining Social Democratic Responses to the Challenge from the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe.” Political Studies 58(3): 410–26.