Daniel E. Ponder

Political institutions are embedded in context; executive institutions are certainly no exception. One of the take-aways from my recent book, Presidential Leverage: Presidents, Approval, and the American State, (hereafter, PL) is that scholars should examine the place of an institution in the public’s judgment to evaluate the degree of autonomy that the institution and institutional actors enjoy. In PL, the institution I am primarily interested in is the American presidency, but the method and theory can in many cases be applied across countries and institutional contexts, though the institutions (e.g. legislative, executive) would change depending on the political system scrutinized. It is my purpose here to write about the American presidency specifically, though in service to a larger, generic framework. I start generally, move to the specific, and end with some suggestions for applying PL in a comparative framework.

The American Case

In PL, I apply the idea of the president as the face of the state, something that is not always the case in other systems. What motivated my thinking is the observation that Americans think of presidential approval by isolating on the president, reporting a number (e.g. 40% approval, which is President Trump’s Gallup approval rating at the time of this writing), without reference to the larger context of government within which all presidents reside. My research shows that examining approval in context of trust in government locates the president in the political system relative to government broadly conceived. Presidents who have high approval may not have high leverage if trust in government is also high. The higher the public esteem for the president exceeds that of trust in government, the more leverage a president has in the political world. That seems to be because the public views the presidency in a much more favorable light than government, so presidents who have high leverage tend to be the “best” or the “only” game in town. Even more interesting, as presidents’ decline in leverage, they are more likely to act in ways to protect their standing and raise it.

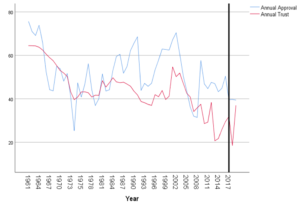

Calculating the Index of Presidential Leverage (IPL) is approval divided by trust in government. Americans have come to trust government less over time, when the public held government in high esteem in the 1950s and early 1960s. However, the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the eras of Vietnam and Watergate, and trust took a beating, falling to levels from which it has never fully recovered (see Figure 1; vertical line is start of Trump administration).

Figure 1: Presidential Approval and Public Trust, 1961-2019

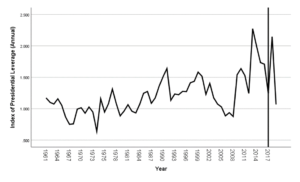

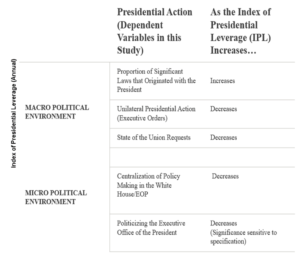

There is substantial variation in the IPL (see Figure 2). The higher the value of the coefficient, the more leverage a president has. The IPL is a relative measure, meaning that high approval ratings are neither necessary nor sufficient for high leverage. Kennedy, for example, enjoyed high approval, albeit at the same time trust in government was high (Figure 1). Thus, his IPL was good, but not spectacular (Figure 2). Carter had mediocre ratings in 1977, his first year in office, and he enjoyed high leverage given trust was extremely low. Thus, for 1977, the presidency had great leverage, though in some realms he failed to capitalize on it. Trump has thus far started in a somewhat stronger position, but the combination of rising trust and declining approval has set him in a lower leveraged position. I will trace Trump’s actions relative to these trends in future work. Figure 3 summarizes the empirical result when leverage identified in the book, when the IPL is used to explore the effect of public opinion of the president, contextualized by trust in government, on various components of presidential action. The macro political environment examines big, large scale politics, such as many of the how big, important, and enduring government actions laws were White House creations as opposed to originating elsewhere, such as in Congress, the size of the president’s legislative program, and the use of executive orders for policy making. The micro environment looks at the White House and Executive Office of the President (EOP), how presidential decisions to centralize policy making in the White House or increase the size of the president’s political staff. These are results as they played out in the administrations of Kennedy through Obama’s first term. Readers will notice that Obama’s leverage was the highest of any president, which may be surprising given he struggled with stubbornly mediocre approval ratings. But recall how low system-level trust was. Trump, too, initially had high leverage, but it quickly plummeted over the course of the two short years of his term. The high IPL was, again, a product of very low trust in government. I am currently researching the impact of the IPL in some of these realms during the second Obama term through Trump’s first two years in office.

Figure 2: Annual Presidential Leverage, 1961-2019

Figure 3: Summary of Empirical Relationships in PL

Thinking Generically about Leverage

How can the concept and method of PL be extended to the comparative context? Can it? Most scholars agree that a democracy needs public support to confer legitimacy on its institutions. To ground the theoretical framework in PL, I drew on the idea of placing the public standing of the executive in context other governmental institutions. This was particularly relevant because in presidential systems, the executive is often separate from other institutions, such as the legislature, whereas in parliamentary systems, they are fused and disentangling them for analytic purposes poses a greater challenge.

To facilitate theorizing about the generic concept of leverage, I modified a perspective developed by David Easton (1965) and his formulation of support, which adapts a systems approach which posits that among other inputs, specific and diffuse supports are vital to the long-term survival of a political regime.

Elite Approval as Specific Support

Easton defined specific support as support for individual leaders. For example, a citizen evaluates a leader based on outputs (e.g. public policy; the state of the economy), or from behind a lens (e.g. partisanship). This evaluation is followed by a reaction wherein support increases, decreases, or stays the same.

When executives deliver on their promises, or when the economy is good, or the country is faced with external threat or crisis, approval for that individual (in this case, the executive) often increases. Generically, any advantage derived from favorable public opinion can be spun to their advantage by any political actor, not just executives. Thus, an executive (president’s) approval rating can be thought of as reflecting that degree of individual support.

Diffuse Support: Trust as Context

Diffuse support is directed at the system itself. In PL, I used public trust as a measure of diffuse support. If trust remains low, executives can find themselves at low or high points relative to that level of trust, and therefore more accurately locate themselves relative to how the public views them relative to the rest of the political system. In addition, countries with separation of powers systems pose challenges to executives more than to individual legislators. Trust in institutions is the expression of public sentiment toward the state, particularly to the democratic state.

Institutions can be considered both as collections of progressively ambitious individual leaders, and as unitary actors. The specific support they have in the form of approval, generated by public evaluations of partisanship and policy output, is compared against diffuse support for the regime itself. Specific support that rises above diffuse regime support affords the president some autonomy and increased legitimacy because they come to personify the state. If specific support for individual executives is high, they take on the mantle of the state; when diffuse support for the system is equal to or exceeds specific support for executives, they have less freedom with which to act.

In a presidential system, trust is the context for political action and signals whose values reign supreme. For example, trust is likely to be high when values of the political class coincide with those of the broader public. The role of trust in leverage is best thought of as a proxy for the public predisposition toward politics and authority in general.

Applying the Framework in Comparative Perspective

Applying the framework in comparative politics is likely to work best when: a) valid, reliable data on public perceptions of both the executive and the system are available; b) the country under consideration is a democracy; and c) the country’s political system is presidential as opposed to parliamentary. But other than the first condition, which is a methodological one, the latter two are not necessary, though it may take a more creative bent to get at the concept. While this is only speculative, it may be the case that Theresa May is the public face of the state in Britain and is the recipient of specific disapproval. On the other hand, Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu may tilt in the other direction, as the recipient of specific approval.

Indeed, the actual measure (approval/trust) is not as integral to the concept as the idea, which is placing the governing actor’s approval in context of overall public support for the political system. Whether that be the legislature or the executive in the numerator is not as important as careful, thoughtful identification of the most important factors. Even in the American case, I am not as wedded to the presidential approval/trust framework. Indeed, in research I am working on now, I am examining alternative measurements, such as presidential approval in context of congressional approval or congressional trust, given that the theory has a strong institutional bent. But it certainly does not have to be the case. Presidential scholars may choose to adopt the PL methodology; others may look at other institutions or replace trust in government with other measures, such as political efficacy if such measures exist. Indeed, in some of the earliest iterations of this project, I employed an average of trust or confidence in the Congress, presidency (as opposed to a president), and the Supreme Court, and applying that concept of government approval as the public support for the institutional context within which the president as an individual had to co-exist. Thus, another key part of the theory is that, except for the numerator, the measures that together make up the denominator should be devoid of specific references to individuals. It is thus left up to the collective set of individual respondents to think in generic or specific terms, as it occurs to them, when asked about the “executive” or the “legislature,” or more broadly, about “the federal government.” That way, the two concepts (the specific, individual approval, and the broader, diffuse system) can be more meaningfully compared. So, for example, parliamentary systems may examine trust in government, or choose to follow methodology similar to PL, such as the Prime Minister over a measure of parliamentary trust, approval, or trust in government generally. In this case, the application is not as straight forward, but theorizing in either a country-by-country framework, or by system-type will be useful.

Conclusion

I have set out in some detail the method and general findings of my research on the American state. It is my hope that PL’s theory and theoretical grounding will be useful to scholars of comparative politics. I am also in the beginning stages of a project with my Drury University colleague, Jeff VanDenBerg, to apply and test the framework in the Middle East. Politicians seek leverage, and this formulation is but one, and a publicly-derived one at that (as opposed to constitutional or statutory). Perhaps the concept of leverage set out in PL will lead to other specifications and applications to generalize and extend the findings identified in the American case.