Daniela Vairo, Nicolás Schmidt, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán

Does the executive’s institutional hegemony represents a threat to the survival of democracy? We seek to answer this question in a recently published online article that is part of a broader academic project coordinated by Prof. Adolfo Garcé .[i] The main objective of the project is to analyze the institutional and ideational origins and adaptation of presidentialism in Latin America. In particular, we claim that the concentration of power in the hands of the president leads to greater instability of the regime.

In this post we refer to the main findings of the component of the project that studies the effects of executive hegemony on democracy survival between 1925 and 2016 in 18 Latin American countries. By executive hegemony we refer to the president’s capacity to exercise political control over other institutions, particularly the legislature and the judiciary, not to his or her constitutional capacity to initiate or veto legislation.

For the classical literature on executive-legislative relations, coordination among powers is essential to stabilize democracy. For the literature on executive-judicial relations, in contrast, the independence of judges is key for protecting individual rights. Integrating insights from both literatures, we argue that concentration of power in the executive branch creates a double risk for democracy: the president can violate the rights of the opposition, or the opposition—anticipating this result—can ally with the military to overthrow the government.

Our analysis shows that presidential hegemony has been one of the main factors of destabilization for Latin American democracy. In contrast, institutionally weak presidents facilitate democratic survival because they lack the capacity—and hence the incentives—to attempt an incumbent takeover. This result challenges an extensive literature that considers executive weakness a problem for governability and a source of democratic instability, and thus contributes to the emerging debates on democratic backsliding.

The perils of executive hegemony

The emerging literature on the judiciary and the classical literature on executive-legislative relations offer two conflicting interpretations of the consequences of presidential power for the survival of democracy. This contrast does not merely reflect that presidential influence has different consequences for different institutions. The contrast reflects different theoretical assumptions about the causes of democratic instability, and about the role of the executive in this process.

The literature on executive-legislative relations typically assumes that the danger to democracy originates in the military, an actor external to elective institutions who can act in agreement with civilian leadership. The conflict between elected branches generates paralysis, triggers political polarization, and thus opens the way to military intervention. The result is an abrupt regime breakdown.

The literature on executive-judicial relations, on the other hand, assumes that the danger to democracy originates within elective institutions. The judiciary’s counter-majoritarian logic restricts unilateral executive action and the tyranny of legislative majorities. Conflict between elected branches and the judiciary generates horizontal accountability and protects the constitutional framework. In the absence of this balance, the result is democratic backsliding caused by government institutions.

Combining these two perspectives, our theory emphasizes the role of the executive as the main source of democratic instability. The executive’s capacity to impose irreversible costs to the opposition expands when the president exercises direct control over other branches. The absence of checks and balances allows the president to adopt policies that undermine the rights of the opposition without facing institutional resistance. This suggests that institutional deadlock is not a source of instability, but rather a potential source of protection for parties that do not control the government. When, in contrast, the executive finds no resistance to impose costs on its adversaries, two outcomes are possible: If the president is successful, democratic backsliding undermines the opposition and reinforces presidential control over government institutions. If the opposition appeals to the military as a preemptive move, the result is democratic breakdown by a civilian-military coalition.

Therefore, our main hypothesis holds that concentration of institutional power by the executive leads to democratic instability. Two alternative causal mechanisms produce this result: an erosion of the rights of the opposition, led by the executive, or regime breakdown, led by the opposition in alliance with the military.

Measuring the institutional hegemony of the executive

To test the hypothesis, our analysis covers all democratic presidential systems in 18 Latin American countries between 1925 and 2016 (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela). The units of analysis are country-years (N = 927) and our dichotomous dependent variable captures the breakdown of democracy into an authoritarian regime. The information on the composition of congress was obtained from an original database compiled for this project.

Our main explanatory variable, executive hegemony over other institutions, is measured through four indicators. Two indicators measure the president’s influence on congress and the remaining two, its influence on the judiciary. The first indicator captures the percentage of seats controlled by the president’s party (or the party’s faction aligned with the president, in cases of factional parties) in the lower (or only) house of congress. The second indicator reflects the percentage of seats controlled by the president’s coalition, an indirect form of control that requires the collaboration of other allies. When a single party supports the president in congress, both indicators take on the same value.

The third indicator reflects the percentage of justices that joined the supreme court or constitutional court during the president’s term of office. For example, if six magistrates out of ten entered the court under the incumbent president (during the current term or a previous term, if the president has been reelected), the indicator reflects that the president and his or her allies in congress had the opportunity to influence the nomination of 60% of the court. If there is a constitutional tribunal separate from the supreme court, the indicator captures the average value for both courts. The fourth indicator, similar to the previous one, reflects the percentage of high magistrates incorporated to the supreme court or constitutional tribunal during any government led by the president’s party. This variable captures an indirect form of influence through other party leaders, e.g., past presidents who nominated the justices. Information on justices was coded from secondary sources.

To minimize validity problems related to the individual indicators, we combine the four items into two alternative measures of presidential hegemony:

- The first index (unweighted index”) is an arithmetic mean of the four indicators.

- The second index (“weighted index”) reflects the result of a factor analysis.

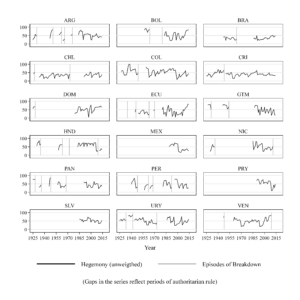

Figure 1 shows the annual values of the non-weighted index (a value of 100 indicates executive hegemony) for each country, during periods of democracy (and semi-democracy) between 1925 and 2016. Vertical lines mark years of democratic breakdown. The figure suggests that longer democratic sequences (for example, Costa Rica since 1948, Chile 1932-1973) tend to occur in systems with moderate levels of presidential control. Democracy can break down at low levels of presidential hegemony (e.g., Uruguay in 1973, Peru in 1992), but systems with high degrees of executive hegemony (e.g., Argentina and Bolivia in the 1950s) have shorter lifespans. Moreover, breakdowns often take place when presidential hegemony is on the rise.

Figure 1. Executive hegemony and democratic breakdown, 1925-2016

Our explanatory models incorporate additional variables to control for alternative explanations of democratic instability. The models include a measure of the president’s constitutional powers over legislation, the effective number of parties in the lower house, the percentage of democracies in the region, to address democratic diffusion, the number of anti-government demonstrations, per capita GDP (natural log), and the rate of economic growth. To account for long-term historical legacies, we incorporate the average Polity score for the century preceding our sample, 1825-1924.

Results

Given the structure of the data, we estimate a discrete-time duration model, based on a probit estimator with random frailties by country. The results are highly consistent in all models and under all specifications: the concentration of institutional power in the executive emerges as one of the main factors linked to democratic breakdown. Against rival hypotheses, presidents with stronger constitutional powers have experienced a lower risk of breakdown. Constitutions adopted in the late 20th century, a period of greater democratic stability, often granted presidents more influence over the legislative process. The only additional variable contributing to democratic survival is the percentage of democracies in the region. Coefficients for other predictors—party fragmentation, mass protests, economic development, growth, and democratic legacies—are statistically insignificant.

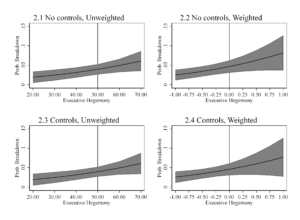

To evaluate the substantive effect of presidential hegemony, Figure 2 simulates the risk of democratic breakdown at different levels of the index, based on the parameters of the estimated models (using the weighted and non-weighted indices, and with and without control variables).

The simulations keep control variables at their observed values and alter the measures of hegemony to generate a prediction. The four panels reflect a consistent pattern: the probability of breakdown increases with the power of the executive, ranging between approximately 2% and 8% per year, or an expected regime lifetime of roughly half a century when the president is weak versus just 13 years when the president is dominant.

Figure 2. Risk of democratic breakdown at different levels of executive hegemony

In summary…

Our findings suggest that the president’s hegemony over other branches of government—but not the president’s formal constitutional powers—represents a major threat to democratic stability. Although the traditional literature on the “perils” of presidentialism anticipated that executive influence over the legislature would reduce the risk of institutional deadlock and democratic instability, the most recent literature on executive-judicial relations suggests that executive control over the judiciary represents a source of democratic backsliding. Our empirical analysis shows that greater direct control of the executive over other branches expands the risk of democratic breakdown. This result holds for a considerable number of cases (18 countries) over an extended period (1925-2016).

The literature on executive-legislative relations often ignored that deadlock represents an institutional equilibrium, and therefore protects actors from an undesirable change of the status quo. The veto exercised by constitutional courts represents a similar outcome. Concentration of power in the executive branch eliminates those constraints and facilitates unilateral implementation of controversial policies. It also allows the government to encroach on the rights of the opposition.

Our results call for a reevaluation of institutional environments marked by divided government or recalcitrant courts, which are often labeled “dysfunctional” because of their inability to produce policy change. Our findings suggest instead that voters should strive to balance the distribution of institutional powers as a way to protect democracy. But the results also point to the limitations of this study and open important research questions for the future.

First, “dysfunctional” institutions represent a safeguard when presidents host hegemonic ambitions, but they also impose policy deadlock for governments that do not purse hegemony. Further research should explore the conditions under which the risk of executive takeover justifies the costs of policy paralysis. Second, our study has focused on presidential regimes, where executive hegemony is easy to identify. However, recent experiences suggest that parliamentary (e.g., Turkey 2003-14) and semi-presidential (e.g., Hungary since 2010) regimes confront similar risks. Further research must determine whether our concern with presidential hegemony should extend into a broader concern with executive hegemony under any type of constitution.

[i] The project is supported by Uruguay’s National Research and Innovation Agency (ANII) under Grant FCE_1_2014_1_103565.