Daniela Rezende and Mariana Cockles

The process of cabinet formation under the Bolsonaro administration generated many uncertainties due to the then-candidate’s assertion that, if elected, he would not replicate old political practices, such as the allocation of ministries in exchange for legislative support, one of the main functioning bases of coalitional presidentialism. In this context, the gender dimension was also a critical aspect given the various sexist declarations of the former federal deputy, as the assertion that he would not employ a woman with the same salary as a man, since women can get pregnant and this would generate a burden for her employer[1].

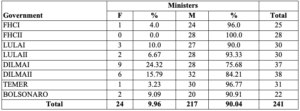

At long last the newly elected president of Brazil recruited only two women in a cabinet of 22 ministries to form his cabinet: Damares Alves, former parliamentary advisor, lawyer and pastor of the Foursquare ChurchGospel, for the Ministry of Women, the Family and Human Rights, and Tereza Cristina, a former federal deputy, president of the Parliamentary Front of Agriculture and Livestock, nominated for the Ministry of Agriculture. However, the (symbolic) presence of women in the Executive, specifically as ministers, is scarce in the history of Brazilian democracy, as shown in the table below:

Ministries of State, according to administration and sex (1995-2019).

Source: Presidência da República. Data of primary setting of Brazilian cabinets.

The data points that, despite the decisional autonomy of Brazilian presidents to indicate his/her ministries, women still find great barriers regarding the occupation of ministerial posts in the country. Considering the offices of Brazilian government between 1995-2019, Dilma’s first term (2011-2014) stands out for having appointed the highest percentage of women to compose its government: 24.32%. Meanwhile, the second term of Fernando Henrique Cardoso stands out for the opposite, since no woman was named minister in his primary cabinet of ministries.

Considering that three presidents were re-elected for a second term during the referred period, it is worth noting that the number of female ministers tends to be higher in first terms: under the Fernando Henrique Cardoso administrations, the numbers was one in the first term against zero in the second; in the Lula governments, the number fell from three in the first term to two in the second; as for the Dilma administration, this number goes from 9 to 6 between the first and second terms. It is noteworthy that, even with such a reduction, the Dilma I and II governments indicated more women (15) than all other governments combined – 15 against the total of 9 ministries.

Although the data is not sufficient to affirm that there is a correlation between the sex of the president and the percentage of women ministers in the office, it is possible to assume it as a hypothesis, considering the symbolic effects of the presence of a woman as Chief Executive, besides its willingness to include more women, thus becoming a “critical actor” committed to gender equity.

However, the fact that the percentage of female ministers tends to fall between the first and second terms of re-elected presidents points to other elements that may influence the dynamics of the formation of presidential offices, especially in the case of Brazil, in which the Executive is characterized by a multiparty structure that emerges from its coalitional logic. Under this form of government, the composition of presidential offices involves negotiations between parties aiming to guarantee stable majorities in Congress, and thus ensuring governability based on a relationship of cooperation and coordination between Executive and Legislative.

Thus, inter-party negotiation is essential for the formation and management of the governing coalition, which once again focuses on political parties as mediators in the distribution of positions, this time in the Executive branch. The Brazilian political science produced several studies focusing on explaining these dynamics (as in AMORIM NETO, 2000; FIGUEIREDO; LIMONGI, 1999; POWER, 2010; SANTOS, 2003), but none of them emphasizes the gender dimension.

Shumaher and Ceva (2015) formulated an inventory of ministers and their respective offices. Considering only the period between 1995-2019, we had 27 ministers. Amongst which 11 have, at some point in their career, held offices related to human rights, women’s politics and / or racial equality. This scene seems to appoint that there is a sexual division of labor in the occupation of ministerial posts, and the tendency for women ministers to be responsible for folders associated with the social area.

The relation between gender and executive power has gained a great deal of attention in the international literature (ESCOBAR-LEMMON, TAYLOR-ROBINSON, 2009, 2012, KROOK and O’BRIEN, 2011). These studies have shown that, in Latin America, the presence of women in political elites, and especially in legislative elites, is important to ensure the presence of women in presidential offices. In addition, there are analysisthat indicate that presidents linked to leftist parties tend to nominate more women as ministers. However, in evaluating the occupation of ministerial folders by men and women, some authors find that there is a sexual division of labor, since ministers tend to occupy folders related to care activities, such as education and social policies, which also seems to occur in the Brazil according to the data presented above.

In addition to references of discussions on the sexual division of labor and the separation and hierarchy between “male” and “female” activities, such studies allow us to rethink the model of supply and demand (KROOK, 2010), since they indicate that the greater presence of women in the political elites favors the presence of women in ministerial offices. In this sense, the discussion here allows to explain some “bottlenecks” regarding women’s access to positions of power and decision-making, such as the women in the Brazilian legislature (only in the last elections the 10% barrier to the Chamber of Deputies was overcome, with the election of 77 federal deputies, which is equivalent to 15% of the total seats in the legislative house) and the generalized organization of Brazilian political parties, with few women in their decision-making bodies, as executive committees and as leaders.

However, as mentioned before, it is worth highlighting that there is a lack of studies that focus on the formation of the governing coalition considering the gender dimension in Brazil. Or even the effects of the presence of women ministers in the elaboration and management of policies under their wardship or in the promotion of actions and strategies aimed at gender equity and transversality. This research agenda should also consider other variables related to the profile of women ministers – such as party affiliation, religion, connections to social movements and lobbies, professional training and career, racial identity – in order to present a more complete and complex picture not only of how gender interacts with the formation and functioning of the Executive power, but also of the intrinsic dynamics of the cabinet configurations in Brazil.

References

ESCOBAR-LEMMON, Maria; TAYLOR-ROBINSON, Michelle M. Pathways to Power in Presidential Cabinets: What are the Norms for Different Cabinet Appointments and do Female Appointees Conform to the Norm? A Study of 5 Presidential Democracies. In: Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, September. 2009.

ESCOBAR-LEMMON, Maria C.; SCHWINDT-BAYER, Leslie A.; TAYLOR-ROBINSON, Michelle M. Representing women’s interests: Empirical insights from legislatures and cabinets in Latin America. In: Midwest Political Science Association conference, Chicago, IL. 2012.

KROOK, M. L. Beyond supply and demand: a feminist-institutionalist theory of candidate selection. Political Research Quarterly, v. 63, n. 4, p. 707-720, 2010.

KROOK, Mona Lena; O’BRIEN, Diana Z. All the president’s men? The appointment of female cabinet ministers worldwide. The JournalofPolitics, v. 74, n. 03, p. 840-855, 2012.

SHUMAHER, S.; CEVA, A. Mulheres no poder: trajetórias políticas a partir da luta das sufragistas no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Edições de Janeiro, 2015.