Appointments to positions in the Brazilian executive branch are directly related to choices about how to build and manage coalitions in multiparty presidential governments. These positions allow for a degree of discretion as to who will occupy them, so they are used strategically by presidents and state ministers and are an essential part of the distribution of power in government.

Within the Brazilian Federal Bureaucracy, political appointment is made through two types of positions that form the high command of the Executive: (i) Functions of trust and (ii) Commission positions (DAS, acronym in Portuguese). It is important to understand the differences between these positions and the implications of these differences in terms of the degree of discretion that is made available to the appointer. Both positions, the Commission and the Functions of trust, have a transitional connection with the public administration; their attributions are exclusive of direction, leadership or advisement; and, both have a trustworthy nature. The essential difference is that Functions of trust are exclusively exercised by occupants of effective positions and public jobs that have entered the government through a public competition; whereas Commission Positions (DAS) are occupied, in minimum percentages defined by law, in one part by career public employees and in the other part by individuals without ties to the public administration who are recruited from outside the public service. It is precisely this second characteristic that allows the government to choose the occupants for these positions, since they can be external to the public service. This, then, grants a degree of freedom to compose the structures of the organs and the political command of the administration, which enables the politicization of the bureaucracy.

Over the years, several steps have been taken regarding the definition of Commission Positions (DAS) in the Brazilian federal government, with the majority of presidents having reformed the legislation that regulates these positions through decrees or administrative rules. The structure of the DAS is currently divided into six levels of function, and subdivided into two categories: DAS-101, referring to positions of Senior Management; and DAS-102, a category that includes positions of Superior Counseling. DAS positions at levels 1 to 3 have little political and managerial responsibility. Positions at level 4 are mid-level positions, such as general coordinators and team leaders. Positions at levels 5 and 6 are high-level decision-making and consulting positions, which include management positions within the structure and are considered as decision-making positions.

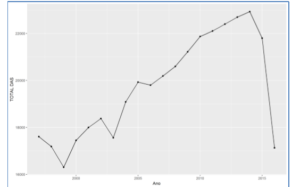

In December 2016, 17,941 employees occupied the so-called DAS group (Direction and Superior Advisory), representing 2.7% of the total number of civil servants active in the Federal Executive Branch. Looking at the total DAS positions during the period from 1999 to 2014, we noticed that there was an increase. Up to 2014, the increase was approximately 30% of the total amount; however, there has been a sharp decline, beginning in 2015, as shown in the chart below.

Graphic 1 – Total DAS positions in the Brazilian Executive Power (1997 – 2016)

Source: Author’s elaboration using data from Boletim Estatístico Pessoal Report – Ministry of Planning, Development and Management

In December 2017, the number of occupants of Commissioned Positions (DAS) reached 12,272. It is currently 12,478, representing a decrease of approximately 50% in the last 3 years. The drop in the number of DAS resulted mainly from Law No. 13,346/2016 which created the Executive Commissioned Functions (FCPE, acronym in Portuguese), under President Michel Temer, and replaced 9,259 DAS by FCPE. That is, it extinguished senior management positions in the federal government that could have been filled by persons outside the public service, reducing the scope for discretionary appointments in the federal government.

The second-level positions of free appointment and dismissal (DAS) seem to be a small percentage of the bureaucracy. However, these approximately 2 percent of positions are important instruments for bargaining with the federal congress. Brazilian multiparty presidentialism demands that the President negotiate with the different parties, often in post-election negotiations, in order to form and maintain majority party coalitions. Thus, the distribution of commissioned positions among the parties that form the coalition can be an important bargaining tool for the President. Controlling a ministerial portfolio, even one that does not offer much influence on policy formulation, may be a way for the President to reward coalition partners by distributing positions within ministries. In recent years, presidents in Brazil have used the distribution of positions in order to consolidate their supporting coalitions.

Furthermore, the distribution of second-tier positions is also a presidential mechanism for maintaining control of bureaucracy, and is used by the president as a strategic tool to control the actions of cabinet members and bureaucratic agencies hostile to his government agenda. Controlling the bureaucracy so that agencies respond to presidential determinations should be considered an important issue for the next government, since president-elect Jair Bolsonaro may find resistance from well-established and institutionalized bureaucracies. For example, when he announced the elimination of the Ministry of Labor, there was an immediate reaction from the bureaucracy that was manifested in a note outlining the history and progress of labor policy in the country after the creation of the portfolio. There was also a public demonstration of about 600 employees who were opposed to the proposal of elimination of the ministry.

Considering this, it is important to question how the strategy of distributing DAS positions in the next government will be handled. So far, the president-elect has repeatedly voiced the need to cut commissioned positions in the federal executive branch. However, following the recent amendment brought about by Law 731/2016, the number of DAS positions available for discretionary appointments has decreased considerably compared to previous years. Given this scenario, it is important to pay attention to the next steps of the elected government regarding the distribution of positions in the second tier. The trading of these positions may lead to new challenges of forming majorities and approving the presidential agenda in a context of multiparty presidentialism.

Bárbara Lamounier – Is a Phd candidate in Political Science at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG-BRAZIL). Earned her master’s degree in Political Science at UFMG and she has a BA degree in Public Management (UFMG).