Mauricio Macri is Finishing his Term

Mariana Llanos

On Sunday 27, October, Argentines go to the polls to elect a new president. Ruling President Mauricio Macri from the centre-right Alliance Cambiemos – now Frente para el Cambio – is seeking reelection, but his chances look shady amid the country’s appalling economic situation. Macri came to power in 2015 promising to tackle high inflation, slowing growth, and crime. He was committed to sweeping market reforms, which would contribute to the ambitious goal of “zero poverty.” However, after four years in government there is not much that Macri can exhibit on the positive side: the critical balance includes massive debt, economic recession, poverty above 35% of the population, and one of the highest inflation rates in the world. Although comparative research shows that incumbents seeking reelection normally get it, it is also known that voters turn away of presidents failing to fix the economy.

The latter became evident after the primary elections of August 11, where the presidential ticket Alberto Fernández-Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, heading an opposition front of reunified Peronist streams, obtained 15% more votes than President Macri. The primaries, which in Argentina are obligatory for parties and citizens, played the role of the (only) reliable pre-electoral survey and set the alarms. The financial markets’ reaction to the prospect of a return of Peronism to power was quick and stormy: the dollar climbed to the value of 58 pesos, a sudden 20% increase, thus causing a new inflationary jump. In the following days, the government tried everything to calm the markets – including the replacement of the minister of economy, a restructuring of the debt, and the return to (limited) exchange controls. The fear was not only that the presidential victory in the October presidential elections was fading away. The prospect of a messy and premature changeover of power – normally scheduled for December – darkened the horizon as well.

To be certain, doubts on Macri’s chances to finish the four-year presidential mandate existed from the beginning. Macri obtained the presidential victory in 2015 by a narrow margin – about 700,000 votes – in the run-off election against Daniel Scioli, the candidate from the ruling Frente para la Victoria, to succeed President Cristina F. de Kirchner. The concurrent congressional elections did not favor Macri’s electoral alliance in either of the chambers, and the alliance won just five out of 24 Argentine provinces. In presidential systems, constraining institutional scenarios put several challenges to presidential agendas, particularly if such agendas focus on policy shifts that involve unpopular economic adjustments. If presidents do not show context sensitivity and a sense of timing to calibrate their reform ambitions, they get into trouble with the many actors holding veto powers. In Argentina, such inability has not only confined presidents to stalemates and lost elections, but also to premature departures from power. In Macri’s case, however, the 2017 midterm legislative elections confirmed supports for the ruling coalition and the phantoms of early departure vanished for a while.

Economic crisis and minority status are regarded as a difficult combination for presidential stability. Consider, in addition, that President Macri was the first president who did not belong either to the Radical Civic Union or the Peronist Party, the two main Argentine political parties and the only that had presidents elected since the approval of the universal male vote in 1916. Macri presided over Republican Proposal (PRO), a center-right party created in 2005 that has been winning the mayoralty of the city of Buenos Aires since 2007. To win the presidential contest in 2015, Macri’s PRO joint the Radical Civic Union and other small political forces and contested the elections in coalition. By winning, the Cambiemos coalition put an end to twelve consecutive years of Peronist rule under the leadership of Néstor Kirchner (2003–2007) and his wife, Cristina F. de Kirchner (2007–2011; 2011–2015). In December 2019, Macri’s constitutional term comes to an end and Peronism will very likely assume the presidency again. Then, Macri will become the first non-Peronist democratic president to have completed the presidential term since 1928. This may be a meagre record for a president who came to power with an ambitious agenda of reforms and accomplished little of it. But the regular changeover of power has some historical significance.

Fixed Terms, Reelection, and Political Instability

The Argentine Constitution of 1853 established a presidential and federal system of government. The president and the bicameral legislature each had an independent legitimacy and were elected for fixed terms. The president was elected by an electoral college for a six-year term and could not be reelected immediately. For eighty years, presidents succeeded each other regularly and the presidential term-limit rule remained unquestioned. Things changed, though, and regime instability became the norm. Between 1930 and 1983 legitimately elected civilian governments were repeatedly interrupted by military coups, and alternated either with military regimes or with regimes that restricted electoral participation through fraud or political proscriptions. The first military coup occurred in 1930, to depose President Hipólito Yrigoyen, and became the first in a series (1943, 1955, 1962, 1966 and 1976). In 1955, President Juan Domingo Perón was deposed after nine years in power. He had been able to get reelected after the 1949 constitutional reform authorized (indefinite) presidential reelection. The last coup in 1976 put an end to another Peronist presidency. Thus, for half a century, democratic presidencies came to an end irregularly with the interruption of constitutional rule.

After re-democratization in 1983, the constitution of 1853 recovered full legitimacy, but completing the constitutional mandate was not possible for every president. Two elected presidents were forced to resign amidst critical socioeconomic contexts, although these times the democratic regime did not collapse with them. Presidential breakdowns replaced democratic breakdowns, a trend that was regarded as a new, distinctive type of instability in Argentina, as well as in other countries of Latin America.[i] Raúl Alfonsín (1983-1989), from the Radical Civic Union, resigned before finishing his six-year presidential term, when Argentina was submerged in hyperinflation and social unrest. Then, Carlos Menem, from the Peronist Party, who had already won the presidential contest, assumed power six months before scheduled. Under his rule (1989-1999), the constitution was reformed and the presidential term altered (shortened to four years, but one immediate reelection was allowed), which let him contest (and win) a second mandate. In contrast, his successor, Fernando de la Rúa (1999-2001), from the opposition Radical Civic Union, did not finish the (shortened) four-year presidential term. He had reached the presidency in 1999 presiding over an electoral coalition, the Alliance, but resigned after two years amid social and political turmoil. Both Alfonsín and de la Rúa governed under severe critical socioeconomic conditions with a shortage of institutional resources, i.e. were minority presidents, and lost further supports in midterm electoral defeats, thus facing serious governability challenges.

Since the constitutional reform of 1994, one more president has been reelected besides Menem: Cristina F. de Kirchner, also from the Peronist Party. Taken together, the Kirchners ruled for twelve consecutive years, or three four-year presidential terms. Another successful, long span for the Peronists, which contrasts with the Radical governments being unable to complete a single presidential term.

Does Macri’s end of mandate represent a turning point in terms of presidential stability? Although Macri is finishing regularly despite adverse conditions, it is difficult to think in long-lasting patterns when electoral uncertainty continues feeding financial volatility and the social and economic context remains unimproved. A good signal is that Argentines go to the polls with expectations of party alternation. Will party alternation favor political stability? When stability is not a systemic feature, as has been shown in this text, actors’ strategies make the difference, and governing in hard times may be challenging even for the party that has been used to deliver the longest spells in power. In the losing scenario, Macri’s centre-right alliance will still retain a considerable portion of the electorate and a non-negligible representation in Congress. This may be the springboard for power alternation in the near future. But if Argentines eventually prefer to trust the ruling president and vote his re-election, will the four-year horizon of a second presidential term awake the old phantoms of instability? A slow (or lack of) economic improvement will clash with impatient demands and expectations, probably quite soon. It seems, thus, that Argentines await more party alternations in the future. At best.

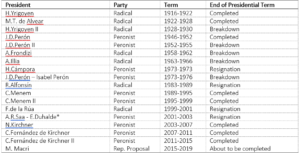

End of Presidential Terms in Argentina. Full and Restricted Democracies (1916 – 2015)[ii]

*Elected by Congress to complete De la Rúa’s term. Between 1955 and 1973, Peronists’ proscription.

[i] Llanos, Mariana / Mainstentredet, Leiv (eds.) (2010), Presidential Breakdowns in Latin America, Causes and Outcomes of Executive Instability in Developing Democracies, New York: Palgrave.

[ii] For further information, consult: Llanos, Mariana (2019), The politics of presidential term limits in Argentina, in: Alexander Baturo / Robert Elgie (eds.), The politics of presidential term limits, Oxford University Press, 473-494

Share this post: